The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

You promised to "defend the Constitution" against "all enemies, foreign and domestic." Now what?

Article VI of the Constitution requires Officials to take an oath "to support this Constitution." Today, 5 U.S.C. 3331 specifies the language of the oath for federal officials. According to this statute, officials must "solemnly swear (or affirm)" that they "will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic" and that they "will bear true faith and allegiance to the same."

Let's say you're a new federal employee and you take that oath. You take oaths seriously. And yet you might wonder what the oath is supposed to mean. On its face, it's not totally clear what it means to "defend the Constitution" and "bear true faith" to it. For example, some people support a constitutional amendment to repeal Citizens United, which would cut back on First Amendment protections. If you took the oath, are you obligated to oppose that amendment in order to faithfully defend the Constitution? Or imagine you work in a federal building and there's a Christmas display that you think violates the Establishment Clause. Does your oath obligate you to take steps to stop the violation, and if so, what steps?

I suspect the answer to both of these questions is "no," and that the history of the oath is helpful to explain its meaning. As a very useful Wikipedia entry explains - big day for Wikipedia in my posts, it seems - the First Congress simply required the oath be a general one to "support the Constitution." The Civil War changed that, though, with oaths during and afterwards mandating or implying an oath of loyalty to the Union and against insurrection.

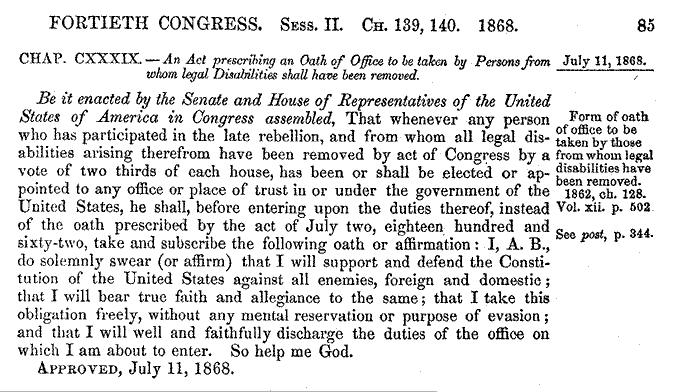

The oath required by 5 U.S.C. 3331 actually dates back to 1868, when it was required of former Confederate soldiers. Here's the text of the 1868 law:

Congress amended the 1868 statute in 1884 so that it applied to all federal officers, not just ones who had taken part in the late rebellion. And the language has stuck around, presently codified at 5 U.S.C. 3331.

So if you're a federal employee, and you wonder just what your oath actually means, I don't think it obligates you to oppose constitutional amendments or to take down questionable Christmas displays that you come across. Instead, I think the oath is probably best understood in its historical context as a promise to oppose political reforms outside the Constitution. You have to stay loyal to the government that is based on the Constitution, and you can't support a rebellion or overthrow of that government. Or at least that's what I think the historical context suggests, which I tend to think sheds some light on what the oath means.

Hide Comments (0)

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mute this user?

Ban this user?

Un-ban this user?

Nuke this user?

Un-nuke this user?

Flag this comment?

Un-flag this comment?