The Shady Statistics Behind the War on Painkillers

The government has doubled down on failed policies, citing deeply flawed studies and misrepresenting data.

HD DownloadAbout twenty-three years ago, public health officials began to notice increases in what would later be called "deaths of despair," referring to suicides, deaths from alcoholism, and drug overdoses. Public health officials and legislators responded by seeking to limit opioid prescriptions for non-cancer chronic pain. Their tactics included violent raids and criminal charges against doctors deemed to overprescribe pain relief. Opioid prescriptions for non-cancer chronic pain fell dramatically.

The war on pain drugs turned out to be a colossal failure. So-called deaths of despair rose even faster, and millions of Americans with chronic pain have had trouble obtaining prescriptions that would ease their suffering because doctors fear losing their licenses. Meanwhile, the government doubled down on failed policies, citing deeply flawed statistical studies and misrepresenting data.

Even the phrase "deaths of despair," coined by Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton, is woefully imprecise: Different types of deaths often get muddled statistically and even definitionally. Who can determine the intentions of drug and alcohol abusers? Who knows if social pressures, mental issues, or the substances involved were the ultimate cause of death? Moreover, many deaths officially ruled as accidental are likely either deliberate suicides or resulted in part from a lowered will to live.

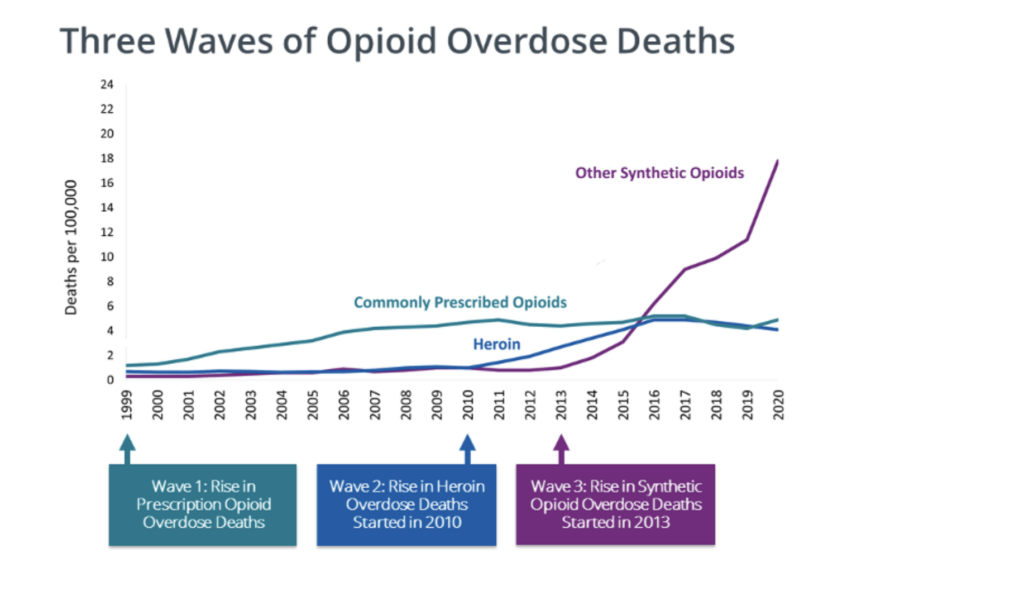

The attack on opioid prescriptions for non-cancer chronic pain began to advance around 2010, and intensified thereafter. The crackdown coincided with—and perhaps caused—a rapid growth in heroin overdose deaths, and later, an explosion in illegal synthetic opioid deaths, primarily fentanyl, an illicitly manufactured substance added to or substituted for heroin to meet the increasing demand for illegal opiates. This pattern of events is illustrated in a graphic put out by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

Indeed, overdose deaths from commonly prescribed opiates increased rapidly from 1999 to 2010, but the chart doesn't tell us how many of the victims legally obtained the opiates. The chosen scale also omits the fact that drug overdose deaths have been increasing at a fairly steady rate since 1979, with no obvious changes associated with the rise and fall of opioid prescriptions for chronic pain. The chart does show how overdose death rates from commonly prescribed opiates did not decline much after 2010, although legal prescriptions went down dramatically. This suggests that these deaths may have involved individuals who bought illegally manufactured opiates, or that the people who lost pain medication as a result of official actions were not the ones liable to overdose.

The increase in deaths of despair obviously merits some policy attention, but labeling it an "opioid crisis," as is common nowadays, profoundly misstates its nature, timing, and likely causes and solutions. To justify restricting opioids for non-cancer chronic pain patients requires specific evidence that people prescribed opioids for pain are the ones dying of overdoses. There's quite a bit of negative evidence on this score, but public health officials have seized on a few positive studies to support their claims.

One influential and heavily cited 2011 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, "Association Between Opioid Prescribing Patterns and Opioid Overdose-Related Deaths," uses a classic prohibitionist tactic. The authors use a sample of 750 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patients who received opioid prescriptions for pain and later died of opioid overdoses, and compare them to a random sample of 155,000 other VHA patients who received opioid prescriptions and did not die of overdoses.

Since all subjects in the study were prescribed opiates for pain, this analysis can't tell you anything about whether those prescriptions are associated statistically with an increased risk of overdose death. Determining that connection would require comparing patients with similar pain diagnoses and matching them for factors such as age, sex, and prior substance abuse. But doing so might not be very informative anyway. Forty percent of the patients who died of overdose had been diagnosed with substance abuse disorders in the 12 months before getting an opiate prescription. Sixty-six percent of them had been diagnosed with some psychiatric disorder. These individuals were more likely to die from overdose or suicide than other patients in the sample. If someone is at risk of overdosing or committing suicide and has opiates, they are more likely to use them than someone without opiates. Thus, suggesting that many opioid overdose deaths might be substitutes for other methods of overdosing or suicide.

The authors did find that patients who were prescribed larger amounts of opiates were more likely to die of overdoses than patients with lower doses. This discovery was used to support CDC guidelines strongly discouraging larger doses. However, the evidence should be interpreted cautiously since the study does not use any controls: The patients prescribed higher doses presumably were in more pain than lower-dose patients, and may well have differed in other ways, such as type of pain or the length of time they had suffered from it. Controls matched as closely as possible to subjects are a basic requirement of good science.

The study has an even more fundamental gap in its analysis: It did not account for quality of life increases in the 99.96 percent of opioid patients who did not overdose, or the bad things that might have happened to the many patients with chronic pain who were denied opioid prescriptions, or given doses too small to control the pain.

Another influential study was "Opioid Prescriptions for Chronic Pain and Overdose: A Cohort Study," which was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine. Almost comically, it had nine authors but only six patients who died of opiate overdoses—a sample size too small to reach any broad conclusions. The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (another comic note is the article mislabels its sponsor as the National Institute of Drug Abuse, suggesting it is made up of junkies rather than researchers). While sponsors do not dictate methods or results, patient treatment issues should be the province of health researchers (like the Veterans Affairs Health Service Research department that funded the previous study), not people focused on fighting drug abuse.

The article begins by rejecting prior work in the field: "The association between prescription opioid exposure and overdose risk has been inferred from uncontrolled case series of autopsies subject to selection bias or from ecological time series studies in which individual-level associations cannot be examined." It criticizes studies like the prior one, which fails to use controls, and statistical analyses like the CDC's claim that if opioid prescriptions and opioid overdose deaths are simultaneously rising, the prescriptions must be causing the deaths.

Despite the small sample size, the authors claim statistically significant results after adjusting for smoking, depression, substance abuse, comorbid conditions, pain site, age, sex, recent sedative-hypnotic prescription, and recent initiation of opioid use. This is logically impossible. There are not even enough observations to estimate the adjustments, much less make any conclusions with statistical confidence. In any event, the authors conclude that whether their results, "were due to patient differences or direct effects of higher doses was not established."

Despite being a decade or more old, these studies continue to be cited by public health officials and policymakers. For example, the 2017 President's Commission On Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis relied on studies published before 2014—usually with data collected before 2011—to claim that opioids prescribed for chronic pain led to abuse. The reason is simple: as the war on opiate prescriptions for non-cancer chronic pain caused prescriptions to decline 60 percent, the number of deaths from opiate overdoses—and also from deaths of despair in general—continues to grow. Moreover, careful, controlled research showed clearly that medically supervised opiate pain management was both safe and effective. The prescription-opioids-caused-the-crisis narrative can only be sustained by relying on old studies.

The cockeyed logic of the President's Commission is illustrated by its section, "Pathways to Opioid Use Disorder (Including Heroin) from Prescription," which references a 2017 article, "Psychoactive substance use prior to the development of iatrogenic opioid abuse: A descriptive analysis of treatment-seeking opioid abusers," that studied people who had sought treatment for opioid abuse. The study's main conclusion was that "only 4% of those who experienced their first opioid via a physician's prescription were truly drug-naive. Rather, more than 95% had significant psychoactive drug experience prior to being prescribed their first opioid." In other words, people who were prescribed opiates and later sought treatment for abuse had almost always begun taking drugs before their prescriptions.

Instead of interpreting the study as evidence that prescription opioids are not the source of drug abuse, the President's Commission claimed that the study "highlights the need for clinicians to screen patients for prior drug use histories." Essentially, the commission would refuse opiates for pain relief to people who have used drugs in the past. To draw such a conclusion would require an entirely different study—one that compares drug-using patients with non-cancer chronic pain who were prescribed opiates versus those who were not prescribed opiates.

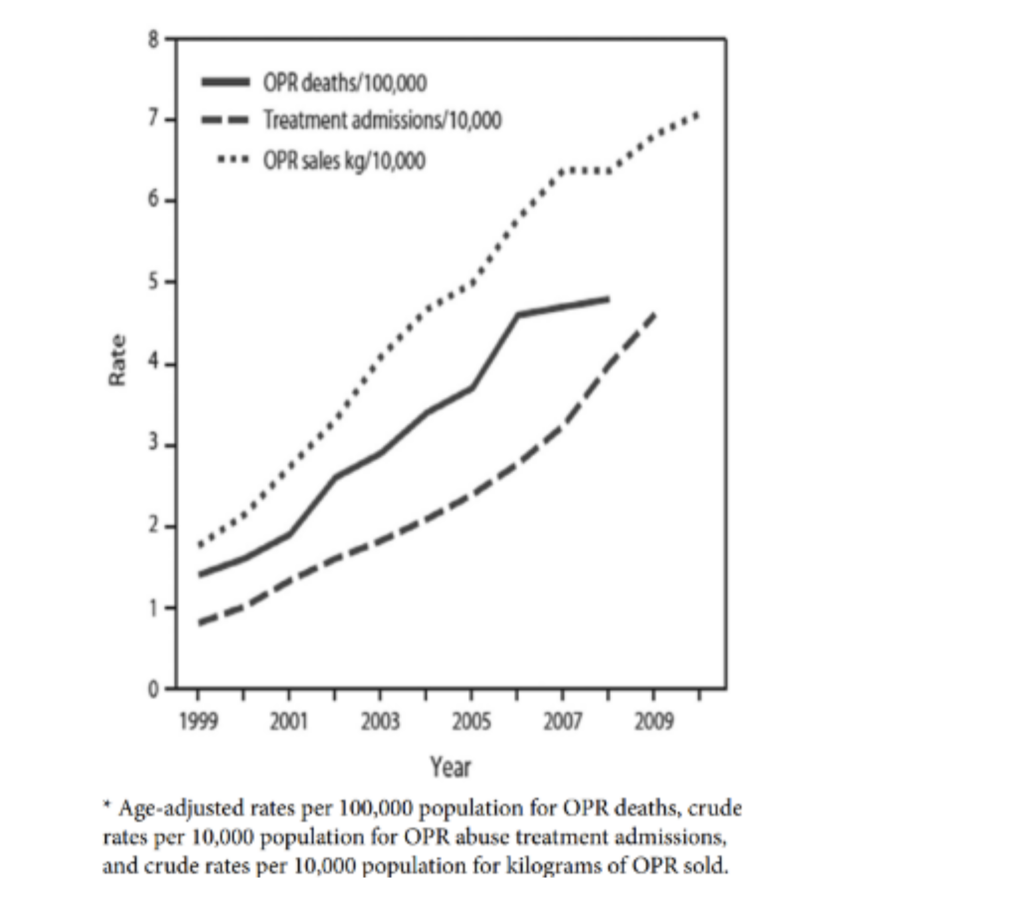

The only article cited that supports any claim that opioid prescriptions led to opioid deaths was the 2012 article "Opioid Epidemic in the United States," which summarizes the results of a 2010 drug survey in overheated blustering language. Literally, the only evidence presented that opioid prescriptions for chronic pain were responsible for opioid overdose deaths was this figure:

The CDC also cited the same figure in 2016—although they prettied it up with colors—to justify new "guidelines" which have since been scaled back. The underlying argument was that the simultaneous rise in all three lines—opioid prescriptions, opioid treatment admissions, and opioid deaths—must have been caused by opioid prescriptions. Of course, this pattern rapidly reversed when opioid prescriptions fell dramatically and the other two measures continued to increase, but that didn't stop officials from using it.

Even back in 2009, before the reversal, this chart did not support the contention. It only shows that the three things are correlated, but does not demonstrate causation. Moreover, it only shows that the three things increase in time—lots of things increase in time without any causal interaction: world population, consumer prices, my age, etc. The chart suggests that the rates of increase are about the same, but that's due to choosing units—all three lines are measured in different units. The chart shows treatment admissions and death both increased by about 4 percent from 1999 to 2009—but that's 4/10,000 for treatment admissions, ten times the 4/100,000 for deaths.

Although there are still many things we don't know about pain management and drug abuse, we do know that long-term pain management is possible with opiates and that the benefits are extraordinary for people suffering from non-cancer chronic pain without unacceptable levels of addiction and abuse. Opiate overdose deaths are very infrequent among people given prescription opiates and have no prior history of drug abuse or psychological problems. The rise in opiate overdose deaths seems to be part of a general deaths-of-despair pattern that began at least a decade before increases in opioid prescriptions for pain management and has not been affected by the decline in those prescriptions.

Show Comments (101)