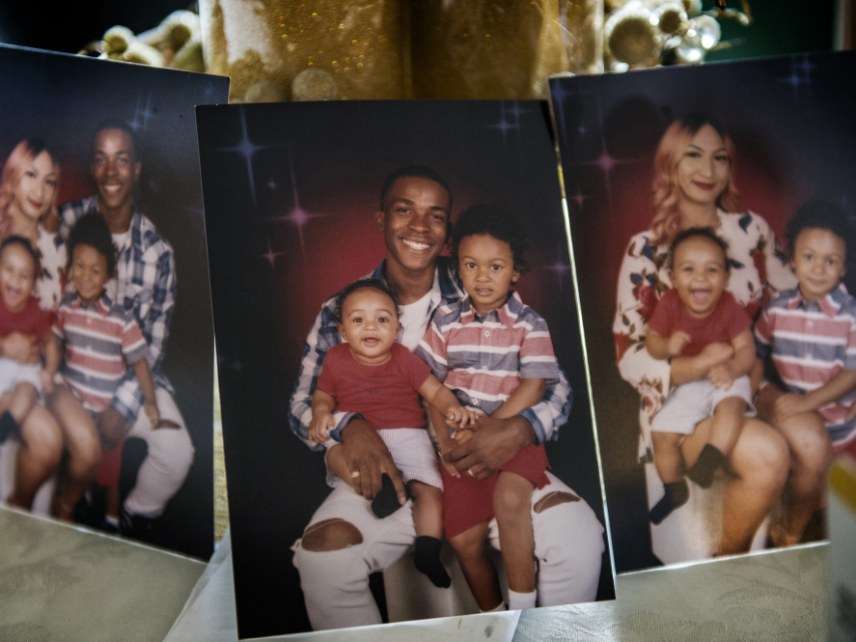

No Charges Against Police Who Killed Stephon Clark, but Anger Has Led to Important Reforms

After police killed an unarmed man in a backyard in Sacramento, outrage led to greater transparency about officer conduct.

There will be no charges against the Sacramento police officers who shot and killed Stephon Clark last year after mistaking his cellphone for a gun. But the outrage that followed Clark's death has led to some real reforms in California, and more may be coming.

Two officers shot Clark seven times following a foot chase. They were responding to some 911 calls about an individual breaking car windows. They cornered Clark behind his grandmother's house. The body camera videos from the two cops showed them attempting to confront Clark, then screaming "Gun!" and opening fire.

It turned out ultimately that Clark was not holding a gun but a cellphone. Protests and an investigation followed.

On Saturday afternoon, a year after Clark's death, Sacramento County District Attorney Anne Marie Schubert announced that she has concluded that the two police officers genuinely feared that Clark had a gun and that they "acted lawfully" when they shot him.

In a lengthy press conference, she walked through all the details, arguing that the officers had honestly mistaken a flash of light from Clark's phone for muzzle fire. Furthermore, an investigation of Clark's phone and the events of that weekend showed that he was deeply troubled following an apparently violent confrontation with the mother of his children. Clark was on probation for multiple crimes (two charges of domestic violence; one for robbery) and was likely concerned about the pending police response to the incident. A search of his phone showed that he had been both texting the woman over and over again, and also had been searching for online tips for killing himself. And he wasn't even stealing anything from the cars he was breaking into.

Police didn't know any of this at the time of the confrontation. But as Schubert explained, all this evidence of Clark's increasingly erratic and desperate behavior would be presented to a jury if she attempted to charge the police in the case. The implication is that it would be hard to get a jury to convict the officers given the entire context of what happened.

She might be right about that, given how hard it can be to hold a police officer accountable for misconduct in a courtroom. Nevertheless, her decision not to charge either officer has inspired a lot of anger. Clark's mother has called the press conference by Schubert a "smear campaign" against her son. Many media outlets and activists have noted that Schubert's office has investigated 34 police shootings and has not recommended charges for any of them. This shooting is being investigated separately by the California attorney general's office.

In a statement, Lizzie Buchen, legislative advocate for the American Civil Liberties Union of California's Center for Advocacy and Policy, opined: "As a society, we give police officers the most significant power we confer on the government—the power to take someone's life. Our laws must set appropriate standards to ensure police officers use that power sparingly and with the goal of preserving human life. Of equal importance is the requirement that officers be held accountable when they violate these standards."

There's a reason for her focus on the standards applied when police shoot citizens. Clark's shooting has prompted pushes to reform California's laws. In the wake of Clark's death, Assemblymember Shirley Weber (D–San Diego) introduced legislation intended to change the rules of force for California police officers. Under Weber's bill, cops could not use deadly force unless "it is necessary to prevent imminent and serious bodily injury or death," with no reasonable alternative courses of action such as deescalation or retreat. The argument here is that had the two officers retreated when they thought Clark had shot a gun, they might have realized he was not armed and that they had been mistaken.

Weber's bill was shelved last summer, but she has reintroduced it with the new legislative session. Her bill is opposed by the Police Officers Research Association of California, the state's top law enforcement lobbying organization, which has promised to craft rival legislation.

The reform push that followed Clark's death also helped create the groundswell to open records of police misconduct so that California media and citizens can find out if officers who kill on the job have a history of bad behavior. For decades, all that information was kept secret from the public, but last year SB 1421 finally opened certain police personnel and investigation records to the public. Police unions, and even the state's Democratic attorney general, are fighting against compliance with the law, but it looks like they're losing.

Show Comments (40)