A Border Wall Is a Bad Idea, but So Is the "Border Security" Democrats Say They Want

Until we fundamentally reframe the immigration debate in terms of human freedom rather than fear, we're not going to see real reform.

We all know that leading Democrats such as Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) are explicitly against President Trump's demand for $5.7 billion in funding for a wall or some other form of fencing or barrier on the U.S. border with Mexico. Yet Schumer, Pelosi, and other members of their party are all in favor of "border security" in the form of increasing crackdowns on employers of illegals, installing "new technology to scan cars and trucks for drugs coming into our nation," and funding "more innovation to detect unauthorized crossings."

As news is breaking of a possible deal to avoid another government shutdown at week's end—one that includes $1.375 billion for "physical barriers" on the border—it's worth asking whether the Democratic position is really that different than Trump's. They say no to a wall but yes to the basic immigration status quo, one that harshly limits the number of legal migrants from Mexico and other Central American countries, forces employers into the role of checking papers of potential employees, and underwrites a system of internal checkpoints that routinely deports American citizens in immigration sweeps. On immigration, as on many other issues, it turns out that the differences between Republicans and Democrats is more about semantics and small details rather than contrasting principles.

In a smart New York Times op-ed, Daniel Denvir makes the case against "border security" that both Trump and the Democrats are insisting on.

There is plainly no need for more security on the border. Illegal entries to the United States (as measured by Border Patrol apprehensions, which the government has long used as a proxy) began to fall at the turn of the century, and have plummeted since 2006. They remain at historic lows today. Those who are coming to the country are often Central Americans fleeing violence that United States policy in the region helped foment.

And when it comes to drugs — a favorite justification of Mr. Trump's for his wall — evidence shows that more "border security" does not stop trafficking. From the 1970s on, every crackdown on a drug-smuggling route, whether it was heroin via the French Connection or cocaine through the Caribbean, has only led to new innovations in the trade that have empowered murderous Mexican cartels. Some scholars even argue that the rise of fentanyl can be traced to drug interdiction.

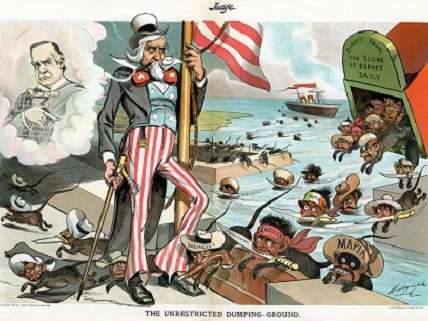

Denvir notes that back in the 1990s, Bill Clinton and the Democratic Party campaigned hard on the supposed ills associated with illegal immigration. As Reason's Matt Welch has pointed out, the 1996 Democratic Party platform sounds uncannily like Donald Trump today on a wide variety of law-and-order issues, none more so than immigration ("We have increased the Border Patrol by over 40 percent," crows the document. "In El Paso, our Border Patrol agents are so close together they can see each other").

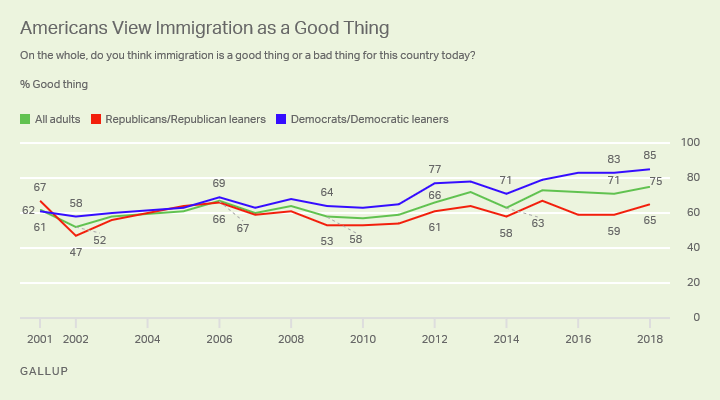

What has happened under Trump is a wholesale reversal of attitudes toward immigrants and immigration. As I noted last fall, a record number of Americans—Republicans along with Democrats—have positive views about immigration and its effects on the country. Denvir is correct to argue that it's time to stop talking about "border security" and to start talking about how to craft an immigration policy that is in step with how the majority of us feel about newcomers.

The border must be demilitarized, which would include demolishing the already-existing wall and dramatically downsizing the Border Patrol. Criminal sanctions on illegal entry and re-entry must be repealed. Opportunities for legal immigration, particularly from Mexico and Central America, must be expanded. The right to asylum must be honored. And citizenship for those who reside here must be a stand-alone cause, unencumbered by compromises that are not only distasteful but also politically ineffectual — and that today would provoke opposition from the nativist right and the grass-roots left.

We can quibble over some of this, but he is, I think, right that we can never get to a good point on immigration policy until the argument is reframed away from questions of "border security." There are a number of powerful arguments in favor of opening the borders, including pragmatic ones (the U.S. economy needs more workers and immigration is the only way to make that happen), comparative ones ("America's share of the foreign born ranks 34th among 50 wealthy countries with a per capita gross domestic product of over $20,000"), and moral ones (law-abiding individuals do not necessarily have a right to welfare but they do have a right of movement; allowing migrants to cross the border fantastically increases their well-being).

Denvir writes from the left (he hosts a podcast for the socialist magazine Jacobin) and the one place where his analysis falters is that he thinks most Democratic politicians "have for far too long let their political opponents define the terms of debate." In fact, they're totally willing accomplices (go read that '96 campaign platform again), partly because they are beholden to organized labor, which has historically argued against more immigration, which is seen (incorrectly) as a threat to native workers' wages. That's also true of Bernie Sanders, the self-described socialist senator from Vermont, who has called open borders "a Koch brothers proposal…[that] would make everybody in America poorer… [and do away] with the concept of a nation state."

There's no question that Donald Trump, virtually out of sheer will, made immigration and a border wall a top policy concern when he entered presidential politics in 2015. His positions on immigration are blissfully fact-free (for instance, despite his statements that we are being overrun down Mexico way, apprehensions on the southern border are one-quarter of what they were in 2000), but they also track with longstanding gripes from fellow Republicans and partisan Democrats. We need a fundamentally different conversation about immigration, one that doesn't see the free movement of people as a problem that must be fixed. And that's going to take a change of heart among both the right and the left.

Show Comments (287)