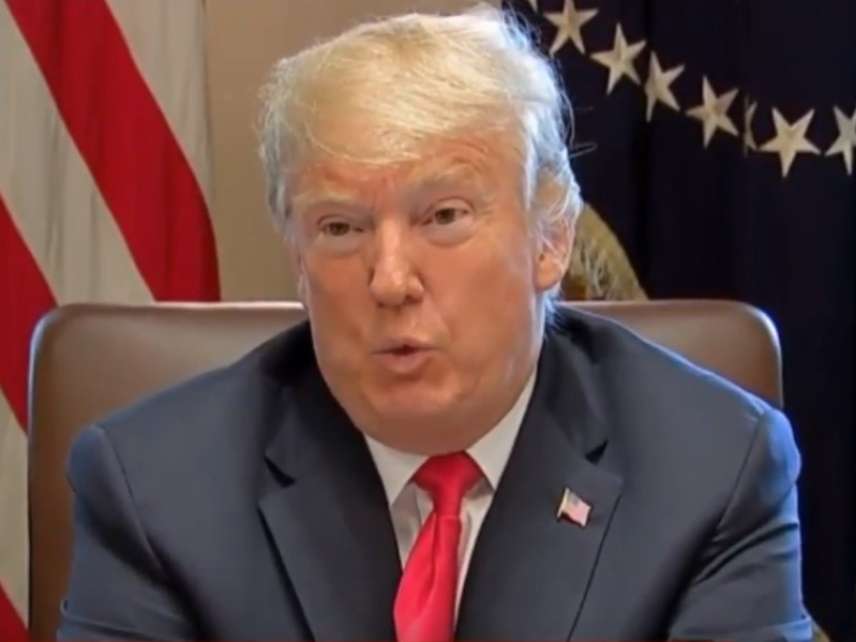

Trump's Cluelessness Remains His Best Defense Against Charges That He 'Knowingly and Willfully' Violated Campaign Finance Law

If Trump did not recognize hush payments to his (alleged) former mistresses as illegal campaign contributions, he is not criminally culpable.

The New York Times reports that the sentencing memo urging "a substantial prison term" for Michael Cohen, Donald Trump's former lawyer, "effectively accused the president of defrauding voters, questioning the legitimacy of his victory." The paper adds that, while the Justice Department has long taken the position that a sitting president cannot be indicted, federal prosecutors at the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New York, which filed the memo on Friday, "believe charges could be brought against Mr. Trump if he is not re-elected."

Defrauding voters, of course, is not an actual crime. If it were, our prisons would be oveflowing with politicians. The relevant offenses in this case would be orchestrating illegal campaign contributions in the form of hush money paid to former Playboy model Karen McDougal and porn star Stephanie Clifford (a.k.a. Stormy Daniels), both of whom claim to have had sexual relationships with Trump. And the most important question in assessing Trump's criminal culpability is whether he understood those payments to be illegal campaign contributions. It is quite plausible that he did not.

Cohen admitted arranging a $125,000 "catch and kill" payment to McDougal from The National Enquirer and paying Clifford $130,000 from his own home equity line of credit. He said both payments were made "for the principal purpose of influencing the election," making the first payment an illegal corporate campaign contribution and the second payment an excessive (and unreported) individual contribution (or loan, since Cohen was ultimately reimbursed by Trump).

According to the sentencing memo, Cohen "acted in coordination with and at the direction of" Trump, a.k.a. "Individual-1." In urging a substantial prison sentence for Cohen, who also pleaded guilty to tax evasion, bank fraud, and (in a separate case overseen by special counsel Robert Mueller) lying to Congress, the prosecutors said they hoped a stiff penalty would have the salutary effect of "deterring future candidates, and their 'fixers,' all of whom are sure to be aware of the Court's sentence here, from violating campaign finance laws."

Contra the Times, the memo does not accuse Trump of "defrauding voters" or "question[] the legitimacy of his victory." But it can fairly be read as suggesting that he "knowingly and willfully" participated in violations of the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA), which would expose him to criminal as well as civil penalties. I'm not convinced that's true, because it seems unlikely that Trump knew enough about the ins and outs of FECA to satisfy the mens rea requirement.

Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani's main defense against charging Trump with criminal violations of FECA is that the hush payments "are not campaign contributions," because they were aimed mainly at avoiding personal embarrassment for Trump and his wife rather than, as Cohen says, preventing revelations that would have imperiled his presidential campaign. Giuliani himself has undermined that argument by alluding to the possible political consequences of press interviews with Stormy Daniels in the late stages of the campaign. "Imagine if that came out on October 15, 2016, in the middle of the, you know, last debate with Hillary Clinton," Giuliani said in a Fox News interview last May. "Cohen didn't even ask. Cohen made it go away. He did his job."

That "didn't even ask" part seems highly doubtful. According to Cohen, he kept Trump apprised of both payments. Still, it's likely that Trump had mixed motives, both personal and political, and he could claim, contrary to what Cohen said in his plea agreement last August, that assuring victory in November was not his primary motivation and that in fact the payments would have been made even if he weren't running for president.

That was essentially the defense offered by John Edwards, who was charged with violating FECA by arranging payments to his mistress (and the mother of his daughter) while he was running for the 2008 Democratic presidential nomination. Edwards' lawyers argued that the payments were aimed at keeping the affair from his wife, who was dying of cancer. In 2012 a jury found Edwards not guilty on one count and failed to reach verdicts on the other five.

Giuliani claims that case vindicates Trump's defense, which is probably reading too much into a mistrial. But the jurors' failure to reach agreement does suggest that proving election offenses like these, which hinge on the defendant's state of mind, is no easy matter. Describing Edwards' prosecution as "a case that had no precedent," the Times noted that "campaign finance law is ever changing and being reinterpreted, with this case falling on one central question: Were the donations for the sole purpose of influencing the campaign or [was that] merely one purpose." Citing election law expert Richard Hasen, the paper said "it is unlikely that the verdict will help politicians better interpret the labyrinth of campaign finance law."

Six years later, campaign finance law is still complicated, and alleged violations can still hinge on debatable interpretations. "At a minimum," former Federal Election Commission Chairman Brad Smith wrote in a Reason essay after Cohen's guilty plea, "it is unclear whether paying blackmail to a mistress is 'for the purpose of influencing an election,' and so must be paid with campaign funds, or a 'personal use,' and so prohibited from being paid with campaign funds." Smith noted that spending "to fulfill a commitment, obligation or expense of any person that would exist irrespective of the candidate's campaign" counts as "personal use," even if it is politically beneficial.

The sentencing memo says Cohen, as "a licensed attorney with significant political experience and a history of campaign donations," was "well-aware of the election laws." He "knew exactly where the line was, and he chose deliberately and repeatedly to cross it." Can the same be said of Trump?

There is reason to doubt it, beginning with Trump's notorious lack of interest in legal niceties. After Cohen pleaded guilty, Trump insisted in an interview with Fox News that "those two counts [related to the hush payments] aren't even a crime." He emphasized that he reimbursed Cohen with his own money, as opposed to campaign funds, which "could be a little dicey." Trump's critics mocked his ignorance of FECA's requirements. "What Trump doesn't know about campaign finance law is, um, a whole lot," wrote CNN political correspondent Chris Cillizza.

Smith argued that Trump, who was allowed to spend as much of his own money on the campaign as he chose, could have paid Clifford directly and reported the transaction as an expenditure under the uninformative heading of "legal services." If so, Trump's failure to take that approach counts as further evidence that he did not have a very firm grasp of FECA. It is hard to "knowingly and willfully" violate a law you don't understand.

Show Comments (199)