Brett Kavanaugh's Discouraging Record on the First Amendment and 'Commercial Speech'

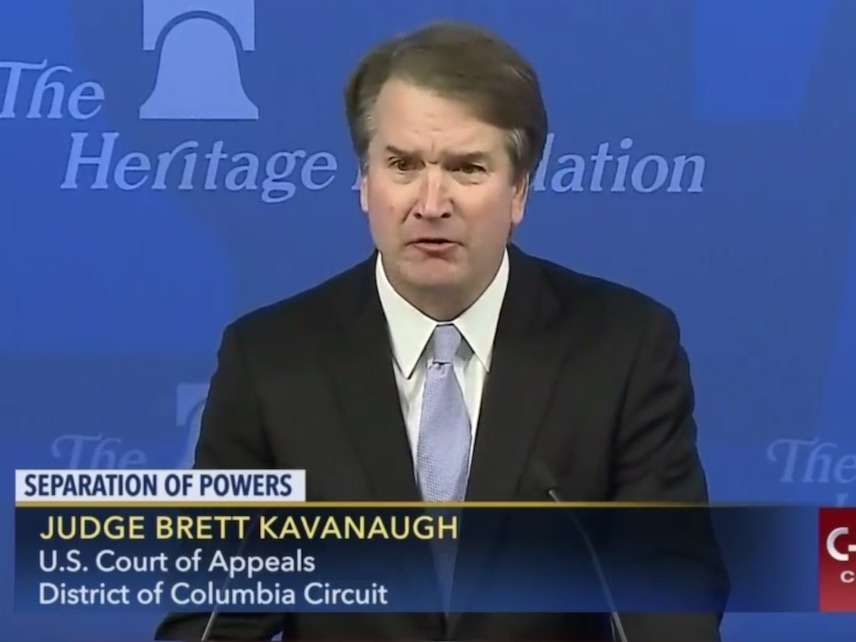

Where does Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh stand on the First Amendment?

Where does Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh stand on the First Amendment? Free speech advocates are likely to be disappointed by the answer when they examine Kavanaugh's vote in an important 2014 case.

That case is American Meat Institute v. Department of Agriculture. At issue was a federal regulation that forced the meat industry to include "country of origin" information on meat packaging. Under Supreme Court precedent, such regulations of "commercial speech" can only pass constitutional muster if they serve a substantial government interest. For example, as the Court declared in Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinarian Counsel of the Ohio Supreme Court (1985), "the States and the Federal Government are free to prevent the dissemination of commercial speech that is false, deceptive, or misleading."

In American Meat Institute, a group of livestock producers, feedlot operators, and meat packers challenged the "country of origin" regulation on First Amendment grounds, arguing that it failed under Zauderer because it amounted to compelled speech that did not advance a permissible regulatory goal.

The federal government ultimately prevailed, with a divided en banc panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit rejecting that First Amendment challenge. D.C. Circuit Judge Brett Kavanaugh concurred.

"I agree with the majority opinion that the First Amendment does not bar those longstanding and commonplace country-of-origin labeling requirements," Kavanaugh wrote. To be sure, he conceded, "the Government cannot advance a traditional anti-deception, health, or safety interest in this case because a country-of-origin disclosure requirement obviously does not serve those interests." But instead of stopping there, Kavanaugh then proceeded to find a different way for the government to win. "Country-of-origin labeling is justified," he asserted, "by the Government's historically rooted interest in supporting American manufacturers, farmers, and ranchers as they compete with foreign manufacturers, farmers, and ranchers." Kavanaugh saw economic protectionism as the way to shield the law from the First Amendment.

For a different perspective on these issues, contrast Kavanaugh's permissive concurrence with the sharp dissent filed by Judge Janice Rogers Brown. "If, as Jeremy Bentham once quipped, a fanciful argument may be dismissed as 'nonsense upon stilts,'" she wrote, "the court's analysis in this case can best be described as delirium on a pogo stick."

In Brown's view, American Meat Institute was a case of judicial abdication. "When we are dealing with fundamental First Amendment protections, as we are here, the burden is on the government, and it is the government that must assert substantial interests," Brown wrote. Yet "not only has [the Department of Agriculture] failed to raise or support any protectionist motive, it has, in fact, consistently denied one."

In other words, Kavanaugh had no business throwing the government a lifeline. As Brown explained, when the First Amendment is at stake, federal judges are supposed to thoroughly scrutinize the law at issue; they are not supposed to bend over backwards in an effort to uphold the restriction.

For free speech advocates, Brett Kavanaugh's concurrence in American Meat Institute represents cause for concern.

Related: Brett Kavanaugh on Obamacare and Judicial Restraint

Show Comments (93)