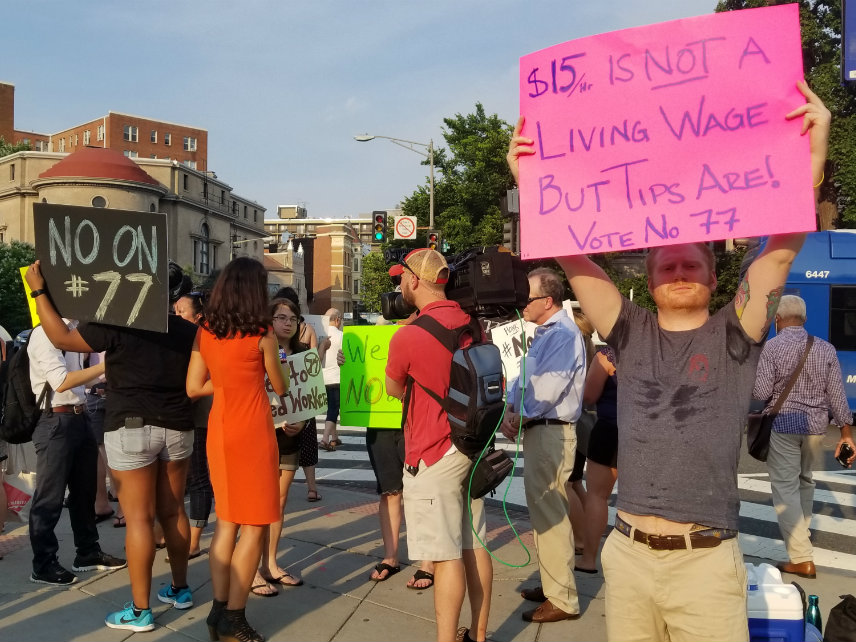

In D.C., Initiative 77 Would Raise the Minimum Wage for Bartenders and Servers. Many Don't Want It.

The national union-backed effort would eliminate tips in favor of higher hourly pay. That's "giving help to people who don't want it," restaurant workers say.

If voters in Washington, D.C., go to the polls on Tuesday and approve Initiative 77—a ballot question that would end the city's minimum wage for tipped employees and raise all restaurant servers' and bartenders' wages to $15 an hour by 2025—bartender Ryan Aston says he would actually end up losing money.

More importantly, he says, he'll probably lose the valuable, but often invisible, help that keeps busy cocktail bars humming along.

"When the cost of business gets too high, the first people to be laid off are going to be the prep cooks, support staff, bussers," says Aston, who bartends at the Hamilton, an upscale bar just a few blocks from the White House. "When labor costs become too high, I mean, it's not a charity. You're in business to make money. I love what I do, but I do it because I get paid."

And how much does he get paid? "A lot more than 15 bucks," Aston says with a laugh. Other bartenders and servers in D.C., despite making a "tipped employee minimum wage" of just $3.50 per hour, say they can pull down $350 to $450 in tips on a good night. That's upwards of $40 an hour.

Of course, not all the nights are that good. But even when things are slow, D.C. law requires that restaurant workers must make at least $12.50 an hour—employers must top-up their pay if they earn less than that much in tips. And once you understand that math, you'll understand why so many restaurant workers in the nation's capital are planning to vote against a proposal that, supposedly, is aimed at helping them.

"It's really frustrating," says Valerie Torres, who works behind the bar at District Anchor on M Street. "For an industry to have outside people determining how we are going to make our money—it's insane. There's no other industry where that happens."

Unlike other recent fights over raising the minimum wage, both restaurant owners and many of their employees have united against Proposition 77. On the other side of the issue is a union-backed nonprofit called the Restaurant Opportunity Center, or ROC, which has pushed successfully for similar laws in places like San Francisco and Minneapolis. Founded after 9/11 to help displaced workers from the World Trade Center's Windows on the World restaurant, the group has morphed into a union front. It made headlines during the summer of 2013 for staging Occupy Wall Street-style sit-ins at some restaurants in major cities.

Saru Jayaraman, ROC's co-founder, bragged in 2003 about the organization's role in helping organize the "non-union 90 percent of New York City's restaurant workforce." ROC aimed at creating a "labor-friendly climate" to pave the way for union organizing drives, the New York Post reported. Richard Trumka, president of the AFL-CIO, has praised the group's work in trying to unionize service sector employees.

"Their endgame is they want to unionize the service industry," says Torres.

In D.C., the local chapter of ROC says passing Prop 77 means "tipped workers will benefit, poverty will decline, tipping will continue, and restaurants will continue to flourish."

Aston, who helped found a nonprofit, the Restaurant Workers of America, to oppose efforts like this one from ROC, sees it differently. "Everywhere they've gone, people are making less money," says Aston, talking about ROC. "If this were a good idea, we'd know by now."

The most frustrating thing about Proposition 77, says Julia Calomaris, a server at Bistrot Du Coin on Connecticut Avenue, is how often people seem to think voting for Prop 77 is helping restaurant workers.

Under a law passed by the city council last year, the minimum wage in Washington, D.C., is $12.50 per hour and will rise to $15 per hour in 2020. But the "tipped minimum wage" is different. It applies only to servers, bartenders, and other tipped employees. Currently, it's $3.50 per hour and will rise to $5 per hour in 2020. If workers don't earn enough in tips to reach the $12.50 per hour threshold, their employers are responsible for making up the difference. In other words, all workers already earn at least $12.50 per hour, but tipped workers have the opportunity to earn more—sometimes significantly more.

"People have no idea how much money you can make working in a restaurant," says Calomaris, who has worked in the industry for 17 years. Imposing a $15 minimum wage and eliminating tips is "giving help to people who aren't asking for it," she says.

If Prop 77 passes, the tipped wage system will be phased out by 2025. After that, tipped workers would earn the same minimum wage as all other workers in the city.

Bowser and most of the members of the city council—the same people who passed the city's $15 minimum wage law just last year—oppose Prop 77, WMAU reports. Only one member of the city council, Mary Cheh (D-Ward 3), supports the initiative.

Opponents of Prop 77, including groups like Save Our Tips (which is backed by the National Restaurant Association), warn that if the tipped minimum wage is eliminated, many restaurants and bars will be likely to institute a service charge on customers' bills. Servers and bartenders will earn less than they do now, and consumers will possibly end up paying more, Save Our Tips says, while owners of restaurants and bars may be forced to cut back employee hours and eliminate positions.

"We've got the best servers and bartenders in the world, here in the United States," says Aston. "I've been to Europe, and the service sucks. There's a reason for that. American culture lives in the bar, and it's so important that we maintain that."

Show Comments (56)