Is Criminal Justice Reform Leaving Small and Rural Communities Behind?

A new report shows that the recent trend of reducing prison populations is heavily an urban phenomenon.

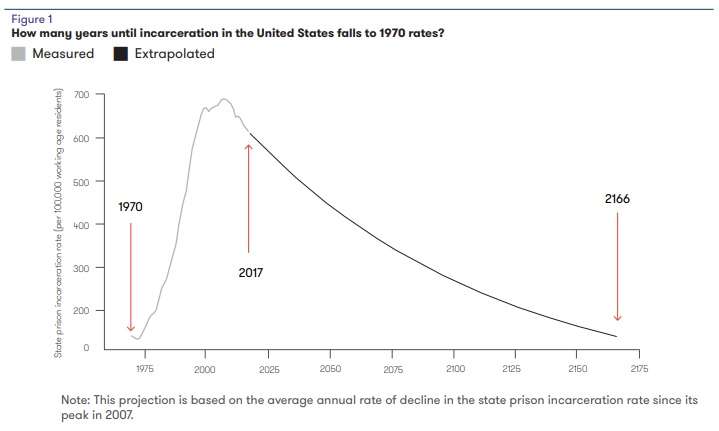

If the current decline in our incarceration rate holds steady, America will return to imprisonment levels not seen since the 1970s by, oh, the year 2166 or so.

Yes, that's about 150 years. No, that's not good news. Today's new report on the state of incarceration in the U.S. by the Vera Institute of Justice isn't actually intended to throw ice-cold water on the successes of modern day criminal justice reform efforts. But it is a sobering look at the slow speed by which we're scaling back on throwing people behind bars, particularly when compared to the rush to lock people up during the drug wars of the past few decades.

Furthermore, this reduction in incarceration is far from evenly distributed across the country. Ten states are driving the biggest decarceration numbers. The other 40 states, when combined, actually show a small increase in incarceration rates.

Fundamentally, what the Vera Institute report shows is a need to look deeper at statistics and adjust how we look at incarceration rates because of such wide variations from state to state. It is true that nationally we've seen a 24 percent drop in prison admissions over the past decade. That sounds awesome. But it's almost entirely due to incarceration reforms in those 10 states. Across the other 40 states, there's been a one percent increase.

The Vera Institute's report is titled "The New Dynamics of Mass Incarceration," and it's all about delving into these numbers and how we interpret them. It's not trying to be a downer, but because of these dramatic differences between states, determining success in criminal justice reform needs deeper analysis beyond a single national trend figure.

The report analyzes some key trends that help explain what's currently actually happening in America's jails and prisons:

Decarceration is primarily an urban phenomenon. In states that are seeing significant declines in people behind bars, it's cities and suburbs that are driving the changes. In New York State, its largest cities have seen drops in prison admissions going back almost two decades. But once you get out of places like New York City and Buffalo, the incarceration rate is actually still increasing. Criminal justice and sentencing reforms are leaving rural and mid-sized cities behind even in states that have seen dramatic drops in decarceration.

The report notes that Virginia, as a whole, has seen only a 4 percent growth in prison population since 2000. But rural communities in the state have seen a 54 percent increase in prison admissions and smaller cities have seen a 34 percent increase.

The report's appendix truly highlights how widespread this phenomenon is. From 2000 to 2013, only four states (South Carolina, California, Nevada, and Utah) saw a drop in the prison admissions from rural communities. Two remained flat—the rest all saw increases. Very similar trends hold in small and mid-sized cities as well.

Shifting incarceration from prisons to jails messes with the numbers. Some states have been reclassifying some felonies as misdemeanors and otherwise scaling back on custodial prison sentences, which is largely a good thing. But there's a down side: There is a trend of shifting sentences from serving time in state prisons to local jails, creating an appearance of decarceration that's not entirely accurate.

The report notes, "Jails are not designed to support long stays, which can mean harsh conditions even if sentences are shorter than prison sentences." Between 2010 and 2015, 11 states reduced their prison populations while at the same time increasing their local jail populations.

California most notably used such a method to reduce its state prison populations in order to comply with a federal court order to reduce overcrowding. Indiana implemented laws that sent people who committed certain low-level felonies to local jails rather than state prison. The end result has been a drop in the state prison population, but the state's overall incarceration has increased due to people being sent to local jails to serve out their sentences instead.

Some states are still seeing all-time high incarceration rates. The report notes that if the state of Kentucky keeps up its current incarceration rate it established in 2000, every citizen of the state will be imprisoned in 119 years. Oklahoma, Arkansas, West Virginia, and Louisiana are all states tagged as still having notable incarceration increases.

But even so there's good news in these states, too. It's just too soon to track the results. Oklahoma voters, for instance, passed an initiative in 2016 reclassifying some drug offenses as misdemeanors. It will be some time before the effect on incarceration of the most recent efforts can be quantified.

Read the full report here. Christian Henrichson, Center Research Director at the Vera Institute, said in a statement that the report's intent is not to dampen interest in criminal justice reform, but to heighten it.

"Vera's research shows there is an urgent need to rethink our approach to ending mass incarceration," he writes. "While we celebrate the successes that have been achieved, the road to countering systemic injustice is difficult and complex. And failure comes at too high a cost. Mass incarceration leaves behind a long legacy that has stripped away the dignity of those behind bars, overly burdened people of color, ripped apart families and communities, and caused intergenerational harm that we cannot begin to quantify. We can and we must do better."

Show Comments (9)