Why You Shouldn't Want Congress To Regulate Facebook & Other Social Media

We need to up our media literacy game, not delegate responsibility to politicians who have no idea what they're doing.

As Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg prepares to testify before both houses of Congress this week, a little more of the internet prepares to die.

We are in a social panic over social media, and the final outcome will almost certainly be some sort of government regulation or self-regulation-by-shotgun (think Comics Code Authority) that will ultimately serve only regulators and the dominant companies that help to write the new rules.

But come on, we've got to hurry up! Science says social media makes us depressed, alienated, lonely, bad-smelling! Social media is a vector for youth violence! FFS, even Facebook, which boasts over 2 billion users worldwide, says it makes us crazy and might even be "destroying how society works!" Worst of all, social media—and all the Russian hacking and fake news it abetted—might have helped Donald Trump become president. Regulate now!

"Net neutrality," the federal government's attempt to play traffic cop and CFO of the internet by regulating the business practices of mobile and fixed ISPs, is so 2015. Remember when Twitter was fomenting revolutions in autocratic hellholes and allowing the world to express its solidarity against terrorism by shading our avatars this or that color? Now, the very government that only grudgingly admitted that yes, it was in fact collecting all of our metadata and more, is riding to the rescue to save our "privacy" and all that's still good and decent in cyberspace. It has summoned Mark Zuckerberg to explain his business, his dark arts, and his intentions. Like past barons of once-new industries whose growth curves have slowed or started falling, he's keen to play ball with the government. "I actually am not sure we shouldn't be regulated," he said recently. "I think the question is more 'What is the right regulation?' rather than 'Yes or no, should we be regulated?'" Folks in meatspace and online media, especially those who have seen their circulations and audiences tank over the past few years due to Facebook's ever-changing plans, priorities, and algorithms, are cheering such developments.

We are in a slow-motion chokehold when it comes to online speech and behavior, and the Facebook drama must be seen in that larger context. Some of the new censoriousness proceeds from congressional action but much of it is cultural. For many in the media, the rise of Trump and the alt-right means that free-speech absolutism must yield to concerns over hate speech, conspiracy-mongering, Russian trolls, and fake news. Individual sites and services such as Backpage, which catered to personal ads that routinely blurred the line between friend-for-pay and prostitution, have been shuttered by the feds, while Craigslist has understandably closed down that whole wing of its operation, which often provided support and community to marginalized groups other than child molesters. Twitter is accused of "shadowbanning" people, mostly conservatives, or purposefully reducing the reach of some people's messages on that network, when it's not simply banning others for speech-code violations. YouTube is "demonetizing" videos with political or sexual themes, thus depriving creators of their God-given rights to make money at YouTube by selling ads against views. (The mass shooter at YouTube's headquarters, a militant vegan, claimed as much.) YouTube's corporate big brother, Google, sells placement in its search engine results and (again, supposedly) tamps down findings that its administrators consider awful or rotten or repellent. Nobody looks at the second page of search results, don't you know, so if you're not first, you're last, or completely immaterial to the public, and that's not fair or something. And then there's Facebook, which has a long history of not giving a fuck about anything other than the passing whims of its creator and the wallets of its investors.

In an online-outrage culture that lurches from one screaming match about the last stand of civilization to the next, it's genuinely difficult to remember any, much less all, of the times Facebook has supposedly violated all of us, its loyal users who provide not just content for the platform but dead souls to whom advertisers can sell shit. Do you remember the time that Facebook's commissars told us that they get to keep our data even when we leave the platform? Or that they tracked us across even outside their "walled garden," used our likes to direct advertising, and employed facial recognition software on us? When they suppressed conservative groups? How many websites made a "pivot to video" at Facebook's urging only to die when audiences didn't follow? What about that 2011 consent decree in which the service agreed to safeguard user data and privacy?

But let's cut to the chase. The real reason many people in Washington and the media are so bent out of shape is because when Facebook wasn't spreading supposedly fake news that supposedly threw the 2016 election to Donald Trump, it was allowing a shadowy, sketchy, pro-Trump group called Cambridge Analytica to "scrape" and "spider" and "mine" your profile and…do what, exactly?

This is actually where all the horror stories about the terrible effects of social media go to die. There appears to be little to no question that Cambridge Analytica broke Facebook's existing privacy policies by using data it had no right to have. Facebook, too, didn't seem particularly vigilant or interested in protecting user data, even though it promised to. These are serious terms-of-service violations and there should indeed be fallout, for Cambridge Analytica and for Facebook.

But what Cambridge Analytica did—use a social network to find and message people who might be interested in Trump—is not so different from what the Obama campaign did in 2012. Indeed, the whole point of a social network is that you can find and reach people who share particular interests and predilections with much greater ease and accuracy. You can do that to start an online group, sell soap, or push particular candidates or issues. Targeted advertising isn't simply a boon to sellers, of course. It also means that recipients are more likely to care about what messages they're receiving.

That basic dynamic is busily being recast as something so sinister and dark that it must be reined in by Congress, industry, or some mixture of both, especially when it comes to politics. Google's former chief technology advocate tells The Atlantic that Cambridge Analytica "passed the data to those who could weaponize it and use to against America, FB's homeland." What? Since when does getting what is effectively a mailing list turn into the ability to "weaponize" anything? So many necessary steps are missing in this equation. Let's say you receive a list of good prospects for whatever message you want to send. What does it take to motivate someone to actually get up and do something, whether buy a car or pull a lever for a candidate? And is that a bad thing, in any case?

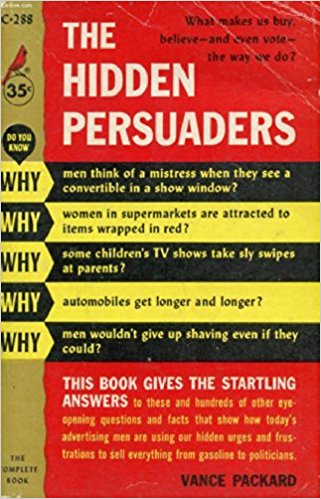

People are talking about "social-media marketing" as if we are automatons being brainwashed by what old-school overwrought critics of postwar abundance such as Vance Packard called The Hidden Persuaders and Wilson Bryan Key (Ph.D.!) called Subliminal Seduction. Fears that we are being secretly programmed by outside forces—ad men, communists, outer-space aliens, gods, you name it—are neither new nor particularly convincing. Those very same anxieties are always thrown at new forms of communication and expression. Early critics of the novel, for instance, were terrified that the original audience of young, impressionable women, would suddenly acting out like the heroines they read about. In the 1950s, comic books and television were charged with creating juvenile delinquents, homosexuals, and worse. In the not-so-distant 1990s, conservative politicians such as Bill Bennett and Bob Dole and liberals such as Janet Reno and Joe Lieberman improbably attacked the Law & Order franchise, The Simpsons, and increasingly ubiquitous cable TV shows for violent crime rate that promptly started declining.

Every new medium breathes fear into the existing order. And that's what is happening now, with a twist: Zuckerberg and his counterparts at other social-media platforms seem ready, willing, and able to trade some level of autonomy for a regulated sphere of activity in which they can lock down their present dominant positions. Twitter and Facebook both have hit rough patches in which they are struggling to maintain, much less, grow in the United States. Twitter lost American users year over year between 2016 and 2017; this year, even before the latest controversy, Facebook lost users in North America. Little more than a decade in, social media companies are growing soft in the middle. It only makes good business sense for them to want to structure their worlds a bit more, doesn't it? It's less important that they are able to grow their audiences than it is for them to keep upstarts from eating their lunch.

But while the solons of social media start working with the government to keep the internet safe from microtargeted ads and to unintentionally usher in a new age of spam and electronic junk mail, it will be up to those of us in the culture at large to create a new ethos of social-media literacy, one that fosters our abilities to filter and critically analyze the information we're sucking in like baleen whales suck in krill. This is less difficult or novel then it might seem. If each new form of media creates a social panic, they also create new levels of self-consciousness. Indeed, in the 1990s, just as cable TV and the World Wide Web vastly multiplied our daily flow of information, popular culture standards ranging from Beavis and Butt-head to Mystery Science Theater 3000 to The Simpsons to The Onion to The Daily Show to Howard Stern's radio program taught us how be more critical about the narratives we were consuming in ever-greater amounts. When it comes to social-media scrutiny, University of Maine journalism professor Michael Socolow floated a framework on how to avoid fake news. To "prevent smart people from spreading dumb ideas," Socolow suggests not sharing surprising news that doesn't include links to evidence or data, being especially skeptical when a story perfectly validates your worldview, and always asking yourself, "Why am I talking?"

Those three practices are hardly a start. But they'll do far more than any likely policy from D.C. or Facebook to empower us to enjoy the internet without turning cyberspace into a shadow of itself. As Mark Zuckerberg talks to Congress, remember that the only regulations that might be worse than those dreamed up by governments are those suggested by an industry itself.

Show Comments (36)