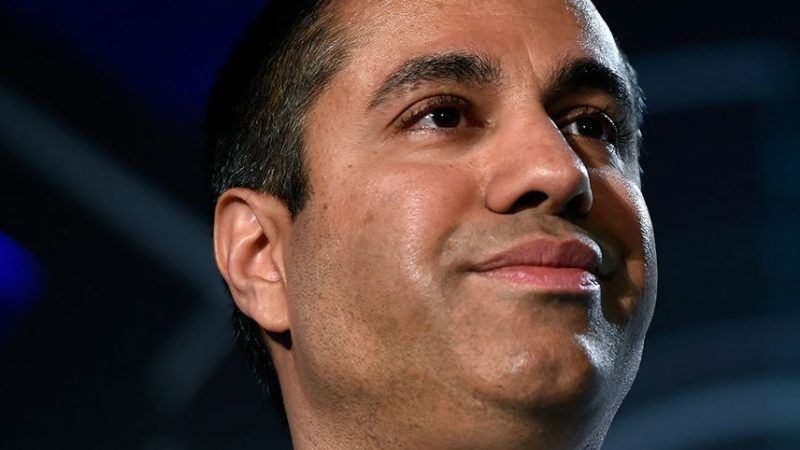

Ajit Pai: 'We Are Returning to the Original Classification of the Internet'

In a Fifth Column interview, FCC chair announces the beginning of the end of Title II regulatory classification of Internet companies, frets about the culture of free speech, and calls social-media regulation "a dangerous road to cross."

Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chair Ajit Pai announced this morning that he is submitting a proposal to repeal what he characterized as the "heavy-handed, utility-style regulation" of Internet companies adopted by the Obama administration in 2015.

Colloquially (if misleadingly) known as "net neutrality" (see Reason's special issue on the topic from 2015) the rules, which included classifying Internet companies as "telecommunications services" under Title II of the 1934 Telecommunications Act instead of as "information services" under Title I, were intended by advocates to be a bulwark against private companies discriminating against disfavored service or content providers. In practice, Pai asserted today in a statement, net neutrality "depressed investment in building and expanding broadband networks and deterred innovation," and amounted to "the federal government…micromanaging the Internet." The measure will be voted on next month.

Pai, appointed to the chairmanship by President Donald Trump after serving as a commissioner since 2012, is a longtime opponent of Net Neutrality, memorably describing it in a February 2015 interview with Nick Gillespie as a "solution that won't work to a problem that doesn't exist." The commissioner foreshadowed today's move in an April 2017 interview with Gillespie, arguing that the Title II reclassification amounted to "a panoply of heavy-handed economic regulations that were developed in the Great Depression to handle Ma Bell." Today's move is already being hailed by free-market advocates and slammed by many in the online activist community.

Pai came on the latest installment of the Fifth Column podcast to explain and debate the announcement with Kmele Foster and myself. You can listen to the whole conversation here:

Partial edited transcript, which includes Pai's views on today's free-speech climate and this month's social-media hearings on Capitol Hill, after the jump:

Foster: As all of you listeners know, because you're weird stalkers, I have a deep background in telecommunication, so I'm actually happy to be chatting with you today, Ajit. And I think you also are announcing some things, and we should perhaps start with the news that you are making.

Pai: Sure, so I'm proposing to my fellow commissioners at the FCC to return to the bipartisan consensus on how to think about the Internet. And so instead of putting the government in control of how it operates and how it's managed, we're going to return to the light-touch framework that was established during the Clinton administration, one that served the Internet economy through the Bush administration and the first six years of the Obama administration. And we'll be voting on this order on December 14th at the FCC's monthly meeting. […]

Essentially, we are returning to the original classification of the Internet.

So, for many, many years, starting with the commercialization of the Internet in the 1990s all the way until 2015, we thought of Internet access as what's called an "information service." And as boring as the phrase is, it actually had significant import: It meant that the FCC would not micromanage how it developed, how it operated. We would let the market develop, and then take targeted action if necessary to protect consumers.

In 2015, that changed, and we switched to calling it a "telecommunication service," essentially treating every Internet Service Provider in the country, from the big ones all the way down to the mom-and-pop fixed wireless providers in Montana, as anti-competitive monopolists to be regulated under 1934 rules that were developed for Ma Bell, the old telephone monopoly. And so we are simply returning that classification back to the information-service one that started under President Clinton. And additionally, we are getting rid of some of the regulations that were adopted under that so-called Title II "common carrier" classification, in terms of the various…rules that were adopted back in 2015.

Welch: So give us a tangible sense of what are things, regulations, that were already happening under this classification, or ones that could be or were in the pipeline, at least until you got in, and how they would impact people's experiences or impact the market in a way that you would think is negative.

Pai: To me, the most pernicious one was something the FCC adopted called the "general conduct" standard. And under this, the FCC didn't specify what conduct was exactly prohibited, they said we'll take a look at any practice by any Internet Service Provider; we'll decide if it is violative of any number of different things, such as free expression online or the like, and we might take unspecified actions to stop it.

Welch: So just to be clear, the FCC had zero authority to discuss or consider the contents of free speech online before 2015. This opened the door to the FCC caring about whether Kmele's dropping F-bombs or whether you're giving a space to people who are cheering on Islamic terrorists or something like that.

Pai: Well, certainly I think that Kmele was safe, and would be safe, I would hope. But what wasn't safe, however…was indicated by my predecessor's comments when he was asked, "Well, how would this Internet conduct standard be applied?" He literally said, "We don't know, we'll have to see where things go." And in the subsequent months, what happened was the FCC initiated an investigation into free data offerings by wireless companies. So if T-Mobile, for instance, said, "You know what…you can watch as much video as you want, exempt from any data limits that might be on your plan." The FCC said, "No, you know what, that free data offering is something that could violate this Internet conduct standard. We're going to investigate it." And they initiated investigations into several other free-data offerings.

And that's the kind of thing that, last time I checked, consumers seem to like the offerings from the service providers, and that's the kind of thing that the FCC was starting to meddle in. And that's one of things that we are getting rid of, is that Internet conduct standard that essentially gave bureaucrats a free rein to second-guess, I think, a lot of pro-consumer and pro-competitive offerings

Foster: Let's let's try to take this from the standpoint of separating the access portion of the conversation and the content portion of the conversation. Because I think for a lot of people, when they hear about the FCC—and we should actually talk about some of the news that the FCC has been involved in throughout the first year of the Trump administration: There were the privacy guidelines that were done away with at the very beginning of the year, at least some rules that, as I believe, had not yet gone into effect. So this is, again, on the content side. We had, actually, the president, who has sent out a couple of tweets. This is your boss, so I'm not necessarily asking you to speak ill of him, but I won't stop you if you wanted to, but he has suggested on some occasions that "some people" are saying, or "a lot of people" are saying, maybe it was "many" people…whatever the phrase is, I think it generally just means that he is saying that there ought to be equal time, for example. So again, another content-related thing that networks ought to be giving equal time to both sides because he felt he was being treated unfairly by network television comedians.

So with respect to the content side, with respect to treating content on the Internet both equally and making certain that it is sufficiently pure, that people's information is being protected by the ISPs who are collecting it, and by various other people who are collecting it online, could we talk a little bit about how the rules that are being introduced or proposed at any rate are affecting that, and what your own thinking is about the way that the FCC should actually be shepherding content on the Internet when it comes to both the privacy of users and giving their data to other people, and when it comes to the things that they're actually consuming online?

Pai: So that last factor is pretty easy for me. I come to the table as a firm believer in the First Amendment, and I think the digital era has only enhanced the potential for free speech and free expression. And to me, at least, the Internet is one of the greatest platforms I think we've ever seen in history, to be honest, for allowing people who, in a previous age, might only finds their views expressed in a letter to the editor, or if they happened to get onto a TV station for an interview. It's given them a platform to be able to speak without that intermediary. That's a great thing. And so that's why the FCC doesn't get involved in deciding what kind of content goes on the Internet, who is going to be allowed to speak, and all the rest.

In terms of privacy, Congress and the president made a decision earlier this year to rescind some the FCC's privacy regulations that were adopted last year.

Foster: And this was like right before the last administration went out, I believe like in December of last year.

Pai: Correct, late last year and in early this year, the current Congress decided to rescind those rules. And so that's why, I think that's one of the questions that we are confronting is, what to do about privacy? And I've long said that previous to these Title II common-carrier regulations, the privacy practices of every online player, whether it was an edge provider like Google or Facebook, an Internet Service Provider like Verizon or Comcast—the FTC applied a consistent privacy frameworks to all those players.

Welch: The FTC.

Pai: Federal Trade Commission, yes. By classifying ISPs, however, as common carriers, the FCC, my agency, created a void. And the reason is because the FTC under the law cannot regulate common carriers, and so that's why late last year, the FCC adopted very onerous regulations for ISPs in terms of privacy. So you had two different agencies adopting two different sets of rules for digital players in the online economy.

Foster: What was onerous about those rules, from your standpoint?

Pai: So, a variety of things. First and foremost, I think it didn't reflect the basic consumer expectation. Consumers have a reasonable expectation of privacy, and so if their information is sensitive as the FTC has long believed, they want to have an opt-in approach. If their information is less sensitive, they're more comfortable sharing it, an opt-out approach, if you will. And the FCC essentially just jettisoned all of that. It ignored the fact of that basic consumer expectation, and it also said that regardless of the fact that 85 percent of Internet traffic is encrypted, it's the HTTPS, nonetheless, we are going to treat it as if the ISPs had uniquely pervasive insight in what consumers were doing.

Foster: And to make it accessible, the way it's generally talked about is: My browsing history, the preferred sites that I visit on a regular basis, what I'm searching for on Google. In some way, shape, or form, the person I buy my Internet connection from has that information. And they might do something with that information, like, say, for example, sell it to marketers, in the nicest, most generous way, sell it to marketers so that they can advertise things to me that I'm interested in. Or to put it in a more nefarious way, they get all of my naughty pornography habits, and they are selling access to that information. […]

But in either case, you're suggesting that before these rules were introduced, there was a void—that ISPs could have been doing this thing, which it's interesting to ask whether or not they had been doing it, and even today there is still a void; effectively those rules never went into force. It has always been the case that ISPs could technically sell that information. Had they—

Pai: Currently, they cannot.

Foster: They can't now?

Pai: No, they can't, because currently they are Title II….So once we remove that Title II classification, the FTC will once again have comprehensive jurisdiction over both ISPs and online content providers, so they'll apply that similar framework to everybody.

Foster: […] So before the rules were adopted, were there restrictions then as well? Those would've come from the FTC?

Pai: Exactly, yes. The Federal Trade Commission would and did apply them consistently to everybody in the online space.

Foster: And were there violations of those norms? What was the reason for reaching for a stricter standard from the FCC standpoint?

Pai: Honestly it was just a power grab. I think the agency didn't really do a reasoned analysis of what it was that Internet Service Providers were doing that would justify those particular regulations. It didn't do, I don't think, at least an intellectually honest assessment of how the Internet operates. Just the mere fact, for example, that every time if you're on your computer, you see "HTTPS," that means your ISP can only see your domain name. They can't see the particular pages that you're on, and also—

Foster: But it could matter. The domain name might matter, if it's HotMoms.com or something, which I don't know that that's a thing; we're not advertising for that.

Welch: No, certainly not.

Foster: I'm going to find out if it's a thing right now. Please keep talking. […]

Pai: And if you think about how a lot of people use the Internet—for example, if you're surfing on your smartphone at home, you're probably using Wi-Fi, so you're—

Foster: It's not a thing, by the way. Go ahead.

Pai: So you're on your home network. But then, as you're driving to work, you might be on your cellular network, which might be a different provider. And when you get to work or go to a coffee shop or your office, you're probably on a third network. And so you use a number of different Internet Service Providers over the course of the day, so no one of them most likely would have pervasive insight into what you were doing on the Internet. And so the simple point I've made is simply just uniform expectations of privacy: The consumers expect that whoever has control over their information, whether it's an ISP or an online edge provider, they should protect that information if it's sensitive. And so that's one of things we're returning to the Federal Trade Commission, would be the comprehensive regulation of everybody who holds online consumers' information.

Welch: Now, the reason that Boing Boing hates you is the two-word phrase—which is loaded, and I think misleading—net neutrality, which you're against. You described it memorably for Reason in an interview, and I'm going to botch it, so I probably won't even try to—

Pai: I remember it.

Welch: Can you render it?

Pai: Back then, I think I called it "a solution that won't work, to address a problem that doesn't exist."

Welch: Yes. Very good.

But surely you understand the motivation for this, and this affects the Title II conversation and everything else, which is that people have a genuine anxiety that the freedom that they have known on the Internet is potentially imperiled, even if it's not now. Even if the problem doesn't exist right now, we don't know what will happen 10 years from now. My God, a lot of things didn't exist 10 years ago that exist now and exert a lot of control. So people are worried that a small number of powerful companies are going to start privileging some content or privileging some other businesses, and kind of start discriminating against others. Is that a problem? Is that something to worry about in an era where we have four companies that everyone, particularly, is obsessing about right now; it's all on the social media, it's Facebook and Google, I guess Apple, and fill-in-the blank on the fourth? There are amalgamations of power that have a disproportionate influence there. So do they not have a point to be concerned about, and are you concerned about that kind of accumulation of power among tech companies here?

Pai: I completely understand that concern, and I would have two responses; one drawing from the past, and one about the future.

With us back to the past, prior to the imposition of these rules in 2015, we had a free and open Internet. We were not living in some digital dystopia in which that kind of anti-consumer behavior happens. There was no market failure, in other words, for the government to solve. Going forward, the question then is, what should the regulations be? Now as you said, there could be some kind of anti-competitive conduct by one or a couple players. And to me, at least, the question is, how do you want to address that? Do you want to have preemptive regulation based on rules that were generated in the Great Depression to regulate this dynamic space, or do you want to take targeted action against the bad apples as they pop up?

And to me, at least, the targeted action is the better approach, for a couple different reasons. Number one, preemptive regulation comes at significant cost. Treating every single Internet Service Provider as a monopolist, an anti-competitive monopolist that has to be regulated with common-carrier regulation, is a pretty…that's a sledgehammer kind of tool. And so that has significant impacts, and we've seen some of those impacts in terms of less investment in broadband networks going forward.

But secondly, I think it also obscures the fact that we want to preserve a vibrant open Internet with more competition. And so to the extent you impose these heavy-handed regulations, ironically enough, you might be cementing in the very lack of competition, as you see it, that you want to address.

And so my argument has been, let's introduce more competition into the marketplace in order to solve that problem. We've been doing that by improving more satellite companies, getting more spectrum out there for wireless companies, incentivizing smaller fiber providers in cities like Detroit, to be able install infrastructure. That is the way to solve that problem. Not preemptively saying, "We are going to impose these rules on everybody, regardless of whether there is an actual harm right now."

Foster: And you said before 2015 there weren't really violations of this standard, and the standard we're talking about here, this is primarily a conversation about access. So it's whether you're using your cell phone to get to websites using the Internet that way, or using your cable Internet provider at home, which oftentimes you only have one of those. The question is whether or not they're prioritizing some traffic versus other traffic, or maybe even just blocking you from getting to certain services, services that they don't make a profit off of your using.

In general, I think it's true that there wasn't a lot of that happening before. But even back in 2015, AT&T was throttling bandwidth on its unlimited data plan. So they're selling you an unlimited data plan, but once you get above say 25 MB, you've downloaded a couple songs, they start to actually scale back the rate of speed with which you can access the Internet. And there's been a fair amount of this throttling going on, and I think part of what a number of people who are concerned about net neutrality regulations want, is, one, they want to know that they can access all of the things at essentially the same rate, that there isn't any prioritization going on, which is a weird thing to want, because from a technical standpoint, there's always some kind of prioritization going on, but that's a separate point. But there is increasing concern, I think, especially as people get much more powerful mobile devices, to have their wireless connection also not be throttled in the way the AT&T was doing. And we still see a fair number of data caps, although they'll talk about them a bit more explicitly now. I believe AT&T was fined for some of that throttling back in 2015.

So there's at least some potential issue here, because there are, in many cases, only a few carriers that you can actually go to to get some of these services. So wireless in New York City, you can get one of, say several: T-Mobile, Sprint, AT&T, Verizon. Most places, they all have their own networks, for the most part. Everybody else is leasing stuff from those guys. But when it comes to Internet service in New York, if you want cable, you talk to Optimum. Or if you want fiber you talk to Verizon Fios. Those are your only two options. And in many places you've got fewer than those two. In a few places you've got more, say, if Google fiber is in your neighborhood or something. In places like that, Net Neutrality could potentially be a real issue for people. So I wanted to be sure to place it in that frame. I am similarly skeptical of the need for it, but I wanted to at least introduce that complexity for you to respond to.

Pai: Absolutely, and this is why what the one rule that we are preserving relates to transparency. I think that consumers, when they purchase a service, should have the right to know from the service provider, this is how we are providing the service, and the terms on which we are providing it, and so they have to disclose that. Additionally, the Federal Trade Commission has authority over unfair and deceptive trade practices, as do state attorneys general, for instance, and other authorities. And so those authorities still remain. If a company is not living up to what they say they're going to do, and they have to disclose that again, under the FCC's framework as I conceive it, then they'll be accountable for that. And so that's the kind of thing that will empower consumers, I think, to understand what exactly it is that an ISP is doing in terms of business practice, and there will be authority still to take care of that problem.

Welch: We've talked a lot on this program over the last several weeks in particular, as there's been hearings on Capitol Hill dragging the social media companies up, and it's kind of tied up with the Russia investigation and all of this. I think we've all at some point characterized this moment as a bit of a "panic." It feels like there is a Capitol Hill regulatory…sort of existential panic about the power of social media companies, and also about the way in which people are worried that Facebook, in particular, could be manipulated by hostile forces. You …don't really work on the generating or commenting on legislation, but just watching this, do you have a bad feeling in your gut about where this is going? And if it went anywhere, if Dianne Feinstein or anyone else was going to write up some new kind of regulation, maybe on political advertising on Facebook or some kind of transparency rules, is that going to fall on your lap, and are you worried about it, and do you feel like taking any sort of preventive shots across the bow?

Pai: Well, generally speaking, I don't take preemptive shots across the bow with Congress.

Welch: I don't know why.

Pai: But I do think that it speaks to the transformative impact the Internet has had. This entire conversation would've been nonsensical to somebody 20 years ago, that you would think the Internet played such a large role in our daily lives. And not just in terms of ordering a coffee or reserving the table at a restaurant, as you said, even the core functions of our electoral process—

Welch: This conversation that we're having on a podcast that people are listening to on their phone.

Pai: Yeah, yeah, exactly right.

Welch: In a subway.

Pai: And that's why I think there's been the impulse in some quarters, and we heard it at last week I believe it was, or maybe two weeks ago, from Senator Franken when he said that I think these net neutrality regulations should apply to Facebook, they should apply to Google, they should applied to Amazon, to all these other online companies. And to me, at least, I think that's a dangerous road to cross.

One of things that's made the Internet the greatest free-market innovation in history, I think, is the fact that policymakers of both parties decided in the 1990s, "You know what, we're not going to treat this like the water company. We're not to treat it like the electric company. We're not going to treat it like Ma Bell. We'll let it evolve and see where it goes." And where it's gone is incredible. Trillions of dollars of value for consumers, trillions of dollars of investments across the country that wouldn't have existed had we treated it like the subway system here in New York. And so, to me at least, I wanted a level playing field for all of these online players, but I wanted it to be a light touch, a market-based playing field, as opposed to the government-knows-best playing field, in which online providers of all stripes have to come on bended knee to Washington and say, "Mother may I?" before we execute on our business.

Foster: Interestingly, I think that's the thing though—when you describe water, power, transportation in New York, the subway is the lifeblood of the city. When it's not working, it's a problem, which is frequent. But for most people, they think to themselves, "No actually, that's precisely how I want my Internet service to work. I want it to be a price that I understand from this provider that I know, with rules that are completely well-known," and in many cases that's the expectation from an economic standpoint, and they use this phrase "natural monopoly." The expectation that there can only be one player eventually. That in order for competition to actually exist, it would be more expensive than having one player actually be dominant in this marketplace. There's an expectation that telecom services which require this really expensive investment in infrastructure are in fact natural monopolies. And as a consequence of that, they've been regulated as such.

So your reference to Ma Bell is something that some people might not appreciate straightaway. It's important to acknowledge that the reason there are so few providers in a lot of these places to begin with is a consequence of proactive, preemptive regulation that helped to create these telecom monopolies in the first place. It created the monopoly with Time Warner in this particular region of the country, where they were the only broadband access provider for a time, and in various other places where Verizon for example, has come in to spend money, to build their own network, to compete to introduce another carrier, the incumbent has been able to actually make it challenging for them by appealing to local officials, which I think is worth mentioning. […]

Welch: I wanted you to a kind of chew on a bit of a paradox that I think you live through, and we all do in a way, which is that legally I don't think, or jurisprudentially, we haven't been in a better moment for free speech that I can think of. The Supreme Court, in particular, is very strong on free speech cases, they just took another three or four this past week….I mean, now…the First Amendment's starting to crowd out other amendments almost in the way that they're judging things. So we have this pretty great bedrock happening.

Culturally it feels like we haven't been as backslid like this in a really long time. Again, this is something we've talked a lot about. I know a couple weeks before the president started talking about equal time and this kind of stuff in his Twitter feed, you made some comments about just how the FCC is on the receiving end of a lot of like, "Hey, these people are either fake news or they're bad, we should look at this and we should…." Complaints about the political content of speech. How do you observe this? Do you feel like we're in a more politically oriented sense of we need to do something, and departing away from the free speech traditions that America has had, even at a time that we've never been more kind of legally free?

Pai: I think you frame the paradox pretty well, from a doctrinal perspective at least. The First Amendment is alive and well, if you look at some of these court decisions. But the problem, as you pointed out, is that there's a culture that is required to keep that promise of free speech alive, and especially if you look on college campuses it's…from Evergreen State to Yale, virtually every week it seems like there's another case in which somebody who just doesn't want to hear different point of view wants to and does in fact shut it down. And I think that's pretty disturbing for what it means for the future of free speech.

Welch: And how does this affect your work?

Pai: Oh, it affects it, I can tell you, just about every day I get multiple emails saying you suck at your job because you're not taking this network off the air. Sometimes it's somebody who hates, say Fox News, sometimes it's somebody who hates MSNBC. You name it. I read this article in my local paper, how on earth can they print something like this?

And look, that's sort of the core of what free press is all about. And so I know it's not going to make me popular, probably among anybody, but I'm going to consistently say that so long as I have the privilege of occupying this position, my ally's going to be the First Amendment. I trust in the marketplace of ideas, and I don't want to be in the business of deciding who gets to speak, and who gets to print, and who gets to think, and who gets to express. That's something for the American people to decide for themselves.

Welch: But don't functionally you have to respond to at least some…I don't know what it is, a process, like a petition, or look into this thing that happens?

Foster: Like if someone says cock-holster on television, like a late-night television host?

Welch: Yeah. Like you have to do something, and spend some minor amount of resources in this, right?

Pai: Well, if there's, say, a broadcast license renewal application somebody can always file what's called a "petition to deny." They'll say you should deny the renewal of this broadcast license for these reasons, and one of the reasons could theoretically be, "I didn't like the content of this broadcast," and the like. And that's kind of thing the FCC traditionally has not countenanced. It's one thing if they're actually violating a rule, but if it's just simply they're broadcasting something you don't like, the political tint of a newscast or whatever, we don't get involved in that sort of thing.

Show Comments (150)