Why Do We Force Employers to Cover the Full Cost of Birth Control but Not Food?

Why the contraception but not the meatball sub?

Two in three Americans think employers should be required to provide birth control to employees through their health insurance plans, even if the business owner has religious objections to doing so, Pew Research Center reported last week.

This is troubling, in part because it shows people supporting a policy that we know violates others' constitutional rights. That's not just my opinion—this is a question the Supreme Court has already ruled on. In its Hobby Lobby decision, a majority of the justices found that at least one class of private employers could not be forced by the government to provide contraceptive coverage if the employer objects on religious grounds to doing so. The Court sat, heard arguments, deliberated, and ultimately concluded that the government doesn't have that authority—that the mandate as applied to closely held businesses was invalid.

Let's set aside the Supreme Court ruling for now, however. It's remarkable that so many people think all employers should be forced to cover their employees' contraception, no matter what, because it suggests that people think birth control is special such that no woman should ever have to pay for it herself. Recall that the government argued in Zubik that it has a compelling interest in ensuring that contraceptives are available at no cost whatsoever to the patient. If a woman has to so much as sign up for a separate insurance plan to get her free contraception, even if that insurance plan is also free, the government says her rights have been violated.

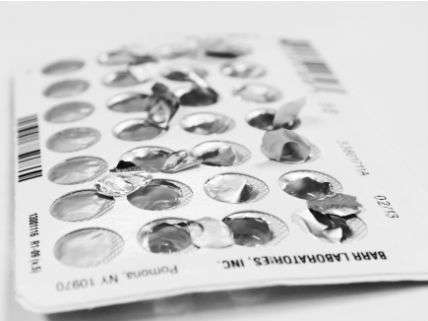

The requirement was the result of a recommendation from the Institute of Medicine (now the "National Academy of Medicine") that women have access to "the full range of Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptive methods [and] sterilization procedures." The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) parlayed that into a mandate that most insurance plans cover all contraceptives, including the morning-after pill, without a co-pay or deductible.

But why is it necessary that contraceptives be not just widely available but also free and provided by a woman's employer? As Nancy Northup, president and CEO of the Center for Reproductive Rights, put it, "access to affordable contraception is essential to women's equality and economic security." Yet there are many things that are important—even crucial—to surviving and thriving the the modern world that people are nonetheless expected to pay for themselves.

Perhaps the most obvious is food.

Surely it's at least as true that "access to affordable sustenance is essential to people's equality and economic security." If I don't eat, I will die. So why shouldn't my employer be required to pay for my meals, above and beyond my base wages, the same way my employer is now required to cover my birth control? After all, I can't make it through the work day without at least one meal. But paying for lunches during the week can cost upwards of a hundred dollars a month; if I have special dietary needs, as many people do, the price tag could be several times more than that. This is a significant burden.

Moreoever, there's a preventive nature to eating: If I do it, I'm far less likely to need to be hospitalized for malnutrition or any of the other medical complications that can result from not having access to food. So why hasn't the federal government passed a law requiring all employers to at least cover one meal per workday?

Some employers do voluntarily subsidize people's meals. The American Enterprise Institute famously boasts that its employees get access to a "gourmet dining room, with a three-course lunch available daily at a nominal cost." It's one of the ways the D.C. think tank attracts top talent. Many big companies have cafeterias on the premises featuring low-cost meal options. Others do monthly staff breakfasts and the like. The place I worked before Reason kept the office kitchen stocked with a never-ending supply of peanut-butter-filled pretzel bites, which saved me on more than one occasion from needing to run out for an afternoon snack when I felt my blood sugar dipping.

Clearly, paying for your workers' food can have positive effects on morale and even productivity. Even still, most businesses opt not to worry about how their workers will manage their food intake, trusting that the people they've hired will make good choices for themselves.

Supporters of the HHS mandate really like to say that religious employers who choose not to offer contraception coverage are "imposing" their religion on their subordinates. But as I pointed out at U.S. News and World Report almost three years ago, that claim disintegrates when you replace "birth control" in the equation with "the meatball sub I had for lunch." If you'll permit me to quote myself:

Few would dare argue an employer who doesn't buy your lunch is relegating you to death by starvation, or even dictating to you what you can or cannot eat. Instead, we all intuitively recognize that workers are compensated in other ways, most notably, through wages. Those wages can be used to buy virtually anything an employee might desire, up to and including a meatball sandwich or a little packet of pills.

The point of this comparison is not to come out in favor of a right to lunch paid for by your employer. It's to highlight the absurdity of claiming that being expected to pay for something out of pocket is practically, legally, or morally equivalent to being "denied access" to that thing. We know this about food. We pretend not to know it, for some reason, when it comes to contraception.

You might be tempted to respond that the fact that lawmakers haven't required businesses to cover the cost of employees' food doesn't mean they couldn't if they wanted to. But the government isn't just arguing that it can force business owners to offer contraception coverage—it's arguing that it's compelled to do so. It has to make that claim, because otherwise the mandate would fail under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which says that a law that substantially burdens a person's religion is only valid if (a) the law furthers a compelling government interest and (b) the law is the least restrictive means to doing so. And to return to where we started, on the question of "whether the challenged HHS regulations substantially burden the exercise of religion," the Supreme Court wrote in 2014, "we hold that they do."

So the government believes it has no choice but to force most employers to cover contraception. It apparently doesn't believe it has no choice but to do the same for food, despite the fact that consuming food is not considered objectionable in the eyes of any religions I'm aware of.

Like birth control, food is quite important to women's quality of life. It has the added benefit of also being good for men. You might even think it more important, since humans tend to die without it. Your chances of needing to be hospitalized are far greater when you don't have access to it, so ensuring access is arguably good for the health care system. Most people feel the need to consume it at some point during working hours, and there's reason to think that subsidizing it is not just good for employees but also has positive spillover benefits for the company. In other words, virtually any rationale for forcing businesses to pay for contraceptives would apply to food as well, and without many of the complicating factors.

So I ask again: By what logic does the federal government have a compelling interest in making sure all women get birth control for free but not a compelling interest in making sure all people get food for free? Why the contraception but not the meatball sub?

Show Comments (310)