Justice Stevens Is Wrong About the Constitution, Again

The retired SCOTUS justice takes aim at the First Amendment, the Second Amendment, and the Fifth Amendment.

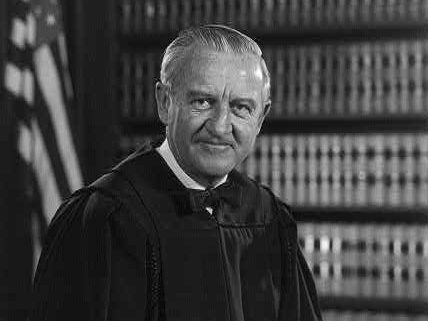

Retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens delivered a speech this week at Washington University Law School in St. Louis. The purpose of the speech, Stevens explained, was to "say a few words about my former colleague, Nino Scalia, and a few of the cases we decided during the 28 years that we served together on the Court."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, among the cases that Stevens brought up for discussion was District of Columbia v. Heller, the 2008 dispute in which Stevens cast the principal dissent and Justice Scalia wrote the majority opinion, holding that the Second Amendment protects an individual right—not a collective one—to keep and bear arms. "Our views diverged," Stevens told his audience, on "whether the framers understood the Second Amendment to protect the right of the people of each State to maintain a well-regulated militia, as I think, or whether the framers instead understood that Amendment as protecting a right of private civilians to own and use firearms for nonmilitary purposes, as Justice Scalia thought." Under Stevens' losing view, the Second Amendment would offer zero constitutional protections for such "nonmilitary purposes" as owning guns for hunting, sport shooting, or self-defense.

The speech was in keeping with Stevens' recent public behavior. Since retiring from SCOTUS in 2010, Stevens has apparently found it quite difficult to keep his legal opinions to himself. Speaking before the Equal Justice Initiative in New York City, for example, Stevens declared, "if I were still an active justice, I would have joined [Justice Samuel Alito's] powerful dissent in the recent case holding that the intentional infliction of severe emotional harm is constitutionally protected speech." Stevens was referring to Snyder v. Phelps (2011), the case in which the Supreme Court ruled 8-1 (Alito was the only dissenter) that the First Amendment covers the right of the Westboro Baptist Church to hold offensive protests outside of military funerals. As the majority opinion of Chief Justice John Roberts noted, correctly, "such speech cannot be restricted simply because it is upsetting or arouses contempt."

Along similar lines, in a 2011 speech at the University of Alabama School of Law, Justice Stevens took to the stage in defense of his 2005 majority opinion in Kelo v. City of New London. "The Kelo majority opinion remains unpopular," Stevens complained. "Recently a commentator named Damon W. Root described the decision as the 'eminent domain debacle.'" (I did. Here's why.) Stevens then tried to justify his lousy Kelo opinion on the grounds that "Kelo adhered to the doctrine of judicial restraint, which allows state legislatures broad latitude in making economic policy decisions in their respective jurisdictions."

Perhaps you've begun to notice a pattern in Stevens' thinking. Stevens prefers the narrowest interpretation of the Second Amendment, thus giving lawmakers maximum power. Stevens prefers the narrowest interpretation of the First Amendment, thus giving censors maximum power. Stevens prefers the narrowest interpretation of the Fifth Amendment, thus giving the forces of eminent domain maximum power. As I have previously observed about the retired justice, Stevens' views about cases such as these "raise troubling concerns about Stevens' commitment to the written Constitution."

Show Comments (64)