Reefer Madness at The New York Times

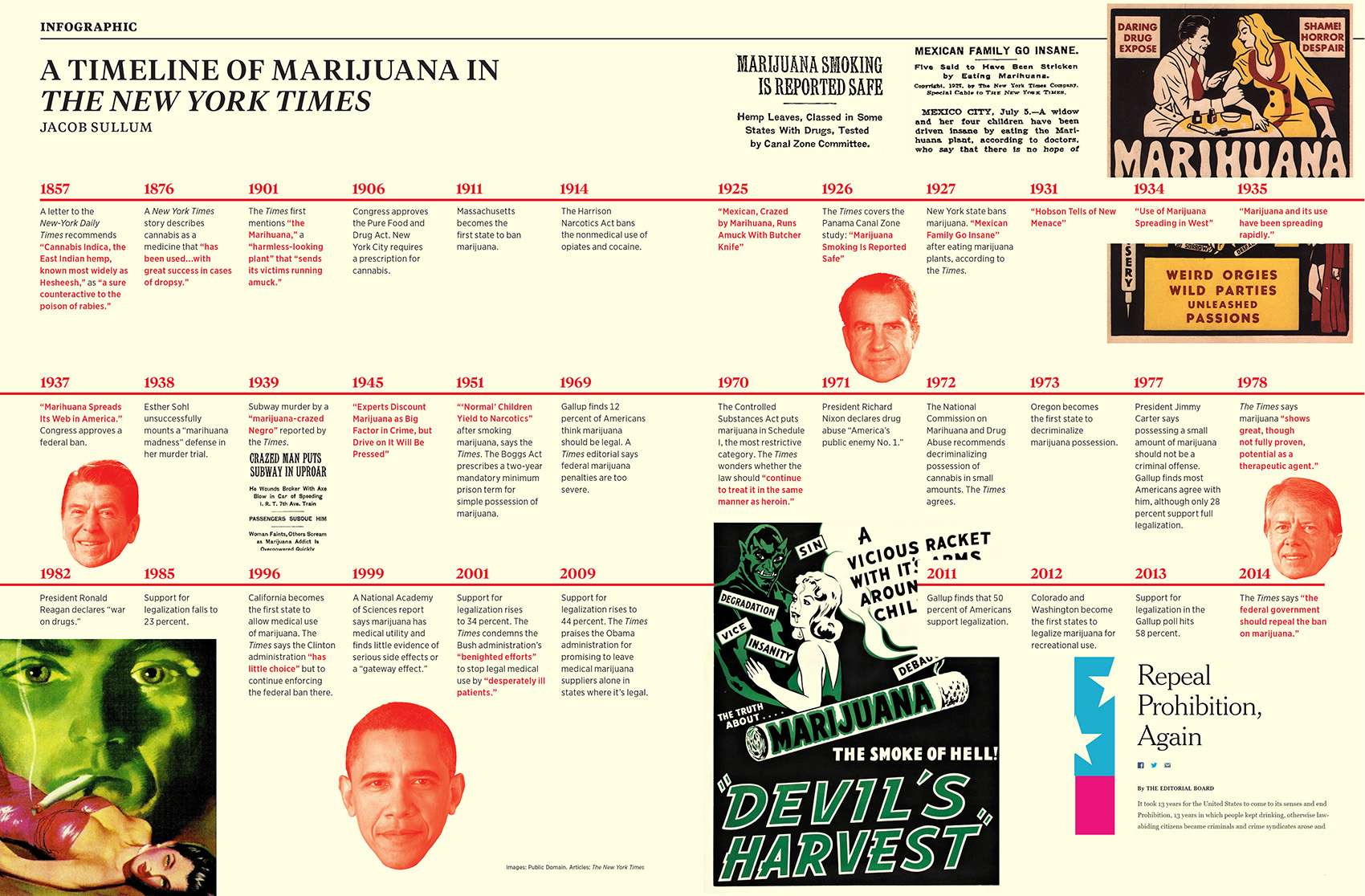

America's Paper of Record, which officially turned against marijuana prohibition in 2014, spent most of the previous century credulously promoting it.

"The federal government should repeal the ban on marijuana," The New York Times declared in an editorial published on July 27, 2014. That week, the paper ran a series of essays fleshing out the case for legalization, including a piece in which editorial writer Brent Staples exposed the ugly roots of pot prohibition.

"The federal law that makes possession of marijuana a crime has its origins in legislation that was passed in an atmosphere of hysteria during the 1930s and that was firmly rooted in prejudices against Mexican immigrants and African-Americans, who were associated with marijuana use at the time," Staples wrote. He mentioned "sensationalistic newspaper articles" that tied marijuana to "murder and mayhem" and "depicted pushers hovering by the schoolhouse door turning children into 'addicts.'" He did not mention that many such stories appeared in The New York Times.

In the context of the era, when papers across the country were running news reports with headlines like "Evil Mexican Plants That Drive You Insane" (Richmond Times-Dispatch) and "Smoking Weed Turns Mexicans to Wild Beasts" (Cheyenne State Leader), the Gray Lady's marijuana coverage during the first few decades of the 20th century was not especially egregious. But to modern eyes, it is remarkably naive, alarmist, and racist. There were occasional bursts of skepticism, but in general the paper eagerly echoed the fantastical fearmongering of anti-drug crusaders such as Harry J. Anslinger, who ran the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) from 1930 to 1962.

The path the Times traveled from promoter to opponent of pot prohibition parallels the journey of Americans generally, most of whom supported legalization by the time the paper's editorial board came around on the issue. In both cases, the single most powerful explanation for the reversal is growing familiarity with marijuana, which discredited the government's claims about its hazards. Since exotic intoxicants tend to be scarier than the ones you and your friends use, it is not surprising that fear of marijuana receded as direct or indirect experience with it became a normal part of adolescence and young adulthood. Conversely, people are much more inclined to accept outlandish claims about drugs they have never personally encountered. In that respect, the supposedly sophisticated and empirically grounded journalists employed by The News York Times are no different from their fellow citizens.

'Mexican, Crazed by Marihuana, Runs Amuck With Butcher Knife'

On the face of it, the fact that marijuana seemed exotic to Americans at the turn of the 20th century is puzzling, since it was a common ingredient in patent medicines during the 19th century. Elixirs containing cannabis were sold as treatments for a wide range of maladies, including coughs, colds, corns, cholera, and consumption. An 1857 letter to what was then known as the New-York Daily Times even recommended "Cannabis Indica, the East Indian hemp, known most widely as Hesheesh," as "a sure counteractive to the poison of rabies."

The letter cited "that famous benefactor to medical science," Irish physician William O'Shaughnessy, who encountered cannabis as a folk cure in India and introduced it as a medicine to Europeans in the early 1840s. By 1876, a Times story (reprinted from The Boston Globe) was describing cannabis as a medicine that "has been used by the faculty here with great success in cases of dropsy."

But that was cannabis, a.k.a. Indian hemp. The first reference to "the Marihuana" in the Times, in a 1901 story with a Mexico City dateline, described it as "a harmless-looking plant" that "sends its victims running amuck when they awaken from the long, deathlike sleep it produces."

The origin of the word marijuana (also spelled marihuana and mariguana) is uncertain. A quarter-century after the term first appeared in the Times, the paper's Latin American correspondent speculated that it "is probably a combination of the names Mary and Jane in Spanish, Maria y Juana." By 1937, the year Congress banned the plant in the U.S., the Times was matter-of-factly asserting that "the weed derives its name from the Mexican equivalent of the names of Mary and John, a fact which those who are engaged in the attack on it say suggests its universal appeal to boys and girls." Anslinger claimed marijuana was derived from mallihuan, the Aztec word for prisoner, but that seems unlikely, since cannabis was not known in Latin America prior to the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century.

In any case, the Times initially drew no connection between marijuana, the drug smoked by Mexicans, and cannabis, the drug swallowed by American consumers of Kohler's One-Night Cough Cure and Dr. H. James' Cannabis Indica. A 1921 report on "a thrilling series of raids" in New York noted that "the only phase of the traffic not represented were dealers in cannabis indica, or hasheesh, an Oriental phase of dalliance with dream-bringing drugs that the police say has been spreading from Turks in New York to natives here."

That "dream-bringing drug" does not sound so bad compared to the intoxicant the Times blamed for a killing spree that left six people dead at a Sonoran hospital in 1925. Except it was the same drug. Under the headline "Mexican, Crazed by Marihuana, Runs Amuck With Butcher Knife," the Times reported that the assailant later "denied all knowledge of the affray."

By the time the remedy and the intoxicant were identified as the same plant, medical use of cannabis was falling out of favor, partly because it could not be injected (since cannabinoids are not water-soluble) and partly because of the general reaction against misleadingly labeled remedies that were often ineffective and sometimes dangerous.

In 1906, Congress approved the Pure Food and Drug Act, which required disclosure of the drugs contained in patent medicines, including cannabis as well as alcohol, chloroform, chloral hydrate, cocaine, heroin, morphine, and opium. Eight years later came the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, which effectively banned nonmedical use of opiates and cocaine. That law did not cover cannabis, but a New York City ordinance enacted the same year required a prescription for "patent medicines containing narcotics," including "cannabis indica."

'Marijuana Smoking Is Reported Safe'

The Times finally seemed to realize that marijuana and cannabis were the same thing in May 1925, when a story about a U.S.-Mexican anti-drug treaty described marijuana as "Mexican hashish." But the paper could not make up its mind about whether the plant was harmless or a terrifying menace to sanity and public safety.

"Marijuana Smoking Is Reported Safe," the Times announced in November 1926, summarizing the findings of an advisory panel appointed by the governor of the Panama Canal Zone. The committee concluded that "the influence of the drug when used for smoking is uncertain and appears to have been greatly exaggerated." It found "no evidence" that marijuana "causes insanity," precipitates "acts of violence," or "has any appreciable deleterious effect on the individuals using it." The article, like almost all of the paper's marijuana coverage prior to the 1950s, had no byline, but it was probably written by Crede H. Calhoun, who lived in Panama and covered Latin America for the Times in the 1920s.

The skepticism did not last long. "A widow and her four children have been driven insane by eating the Marihuana plant," a dispatch from Mexico City declared eight months later. "Doctors…say that there is no hope of saving the children's lives and that the mother will be insane for the rest of her life." According to the story, which appeared on July 6, 1927, the unfortunate family ate the marijuana accidentally, having inadvertently gathered it with "herbs and vegetables growing in the yard."

The idea of marijuana-induced insanity was familiar, but the claim that people can die from a marijuana overdose was new—and is still unverified 90 years later. Also puzzling: the notion that fresh marijuana, which is not psychoactive, would have any noticeable mental effect at all.

But wait. In 1929, the Times covered a decision by Panama's Supreme Court declaring that marijuana was not prohibited in that country because it did not qualify as a "dangerous drug." The article, presumably written by Calhoun, quoted the report to the governor of the Canal Zone, along with the conclusions of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, established by the Indian government in 1893, which found that "not a single medical witness could prove clearly that the [cannabis] habit gave rise to mental aberration."

In 1931, a different government-appointed commission heard testimony that took a dimmer view. Richmond P. Hobson, a former Alabama congressman who had become an anti-drug crusader, made the case for a marijuana ban before the Wickersham Commission on Law Enforcement. "In excess," he said, the drug "motivates the most atrocious acts."

Six months later, Anslinger announced that he was preparing "a uniform law to prohibit the growing of marijuana plants" for state legislatures to enact. At that point about 20 states, including California, New York, and Texas, already had banned the drug. According to the Times, "There are no Federal laws on the growth or use of marijuana, the plant being grown so easily that there is almost no interstate commerce in it." Anslinger, reflecting the contemporary consensus about the extent of the federal power to regulate interstate commerce, "said the government under the Constitution cannot dictate what may be grown within individual States."

As late as January 1937, the Times was still saying the FBN, Anslinger's agency, "has admitted that its hands are tied by the fact that the marihuana weed is indigenous to so many States that its distribution is an intrastate problem." That was just half a year before Congress banned the plant.

'Poisonous Weed…Peddled to School Children'

During the 1930s, any trace of skepticism about the purported hazards of marijuana disappeared from the pages of the Times. A 1932 article casually described it as "a narcotic that gives the addict murderous tendencies." The story also claimed widespread "marihuana addiction among the leaders of jazz orchestras," who "find it necessary to take it before playing."

Music critic Gama Gilbert, in a 1938 New York Times Magazine piece about swing bands, observed that "the swingster will smoke his 'reefers' so long as he needs it, and he will need it so long as the demands of his job and its material rewards remain incompatible with human physical resources." But Gilbert averred that the "muggler" who believed marijuana put him "in the groove" was mistaken: "Actually his playing deteriorates and the deeper sources of his talents become dissipated. He is, as swing lingo has it, 'beat.'"

Black jazz musicians were not the only ones smoking reefers. A 1933 story said marijuana use "constitutes an ever recurring problem where there are Mexicans or Spanish-Americans of the lower classes." A 1934 report from Denver said "the consumption of marijuana appears to be proceeding virtually unchecked in Colorado and other Western States with a large Spanish-American population." While "the drug is particularly popular with Latin Americans," the paper reported, "its use is rapidly spreading to include all classes."

In 1926, the Times reported that there was "no evidence" that marijuana "causes insanity," precipitates "acts of violence," or "has any appreciable deleterious effect on the individuals using it." But the skepticism did not last long. "A widow and her four children have been driven insane by eating the Marihuana plant," a dispatch from Mexico City declared eight months later.

According to "some authorities," the Times said in that story, this "poisonous weed which maddens the senses and emaciates the body of the user…is being peddled to school children." It added that "most crimes of violence in this section, especially in country districts, are laid to users of the drug." The Times did not cite a source for that assertion, but it sounds like Anslinger, who claimed that marijuana-induced violence was common and kept a file of grisly crimes he attributed to the drug, such as the 1933 murders in which a young Tampa man named Victor Licata used an ax to kill his parents, two brothers, and a sister. Despite Anslinger's claim, the psychiatric records compiled after Licata's arrest made no mention of marijuana.

By 1934, Anslinger seemed to be agitating for the federal ban he had described as unconstitutional three years before. "The Federal Government is powerless," the Times reported, citing FBN officials, "because marijuana was left out of the Harrison Act under which the bureau gets its authority to stop the traffic in opium and its derivatives."

Marijuana came late to New York City, where police were still being trained to identify the plant in 1936, nine years after the state legislature had banned it. But soon cops were making a show of seizing and destroying it. On August 13, 1936, New York Police Commissioner Lewis Valentine poured gasoline onto a pile of marijuana collected from three boroughs of the city, lit a newspaper, and tossed it onto the contraband. Police claimed the pile, which measured 10 feet high by 50 feet wide, contained enough marijuana to make 12 million "narcotic cigarettes" worth $3 million—about $53 million in current dollars. "This is an extremely dangerous weed," Valentine said, "and we'll do everything in our power to stamp it out."

In January 1937, the Times described an anti-marijuana campaign aimed at teaching young people "the reasons for its general designation as 'the killer drug.'" That June the paper reminded its readers that "public and private agencies are campaigning against the narcotic as the 'most pernicious' and one of the most widely used of drugs," a substance that "may produce criminal insanity and causes juvenile delinquency."

Two months later, in a one-sentence story dated August 2, 1937, the Times noted that "President Roosevelt signed today a bill to curb traffic in the narcotic, marihuana." That was the Marihuana Tax Act, which effectively banned the plant by imposing prohibitive registration, record keeping, and transfer tax requirements, violation of which triggered criminal penalties. Like the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, the marijuana law was framed as an exercise of the congressional tax power, thereby avoiding the problem noted by Anslinger: that the Commerce Clause, as it was then understood, did not cover intrastate production and distribution of marijuana—or of anything else, which was why alcohol prohibition had required a constitutional amendment.

Since every state already had its own marijuana ban by 1937, the federal law was almost anticlimactic. Judging from an exchange on the floor of the House a few days before that chamber approved the Marihuana Tax Act, the legislators who voted for it did not necessarily know what they were banning. The Republican minority leader, Bertrand Snell of New York, confessed, "I do not know anything about the bill." The Democratic majority leader, Sam Rayburn of Texas, educated him: "It has something to do with something that is called marihuana," Rayburn said. "I believe it is a narcotic of some kind."

'Marijuana Madness…Made Wrong Things Seem Right'

The Times continued to blame marijuana for violence, especially violence by people with dark skin. "Police pointed out that many of the other killings and attacks on women in hotels and hospitals have been done by Negroes," said a story about the rape and murder of a Chicago nursing student published a few weeks after Roosevelt signed the Marihuana Tax Act. "Many youths on the South Side are smoking marijuana, the police said, and the effects of the illegal weed have incited them to attack white women."

All this talk of marijuana-induced violence seems to have made an impression on Ethel Strouse Sohl, a 20-year-old New Jersey resident who, together with an 18-year-old accomplice named Genevieve Owens, carried out a series of armed robberies in the Newark area. On December 21, 1937, the two young women held up a bus driver, William Barhorst, who tried to grab Sohl's sawed-off rifle. The gun went off, killing Barhorst, a 37-year-old father of two. Sohl and Owens got away with $2.10 in change.

During the ensuing murder trial, which the Times followed closely, Sohl, the daughter of a Newark patrolman, claimed she committed her crimes under the influence of "marijuana madness," which "made wrong things seem right." Sohl said she began smoking reefers at 14 and did so before each of the three robberies. To back up her claim that the marijuana made her do it, Sohl's lawyer presented testimony from the Temple University pharmacologist James Munch, who the year before had testified in favor of the Marihuana Tax Act.

Judge Daniel Brennan would not let Munch testify about his experiments with dogs. "He's going to testify about marijuana's effect on dogs and then say it's the same as on humans," the judge remarked. "What kind of testimony is that?" But Brennan did let Munch talk about the conclusions he drew from experimenting on himself and studying "100 Mexicans in a hospital in Nevada." Based on that research, Munch claimed that "continued use of the drug leads to mental degeneracy." That statement prompted the prosecutor to ask, "Doctor, are you a mental degenerate?" Unfazed, Munch opined that Sohl's crimes were caused by marijuana.

The jury did not buy it. Sohl and Owens were convicted and sentenced to life at hard labor. Perhaps the jurors were swayed by prosecutor William Wachenfeld's warning during his summation. "Marijuana never had anything to do with this case," Wachenfeld said. "If you men open the door to a fantastic defense of this kind, it will be all right for anyone to commit a murder if only he first smokes marijuana."

The failure of Sohl's defense did not deter the Times from continuing to draw a connection between cannabis and killing. In 1939 there was the "marijuana-crazed Negro" who "went berserk in a crowded express train," killing an investment banker with an ax blow to the head. In 1941 there was the sailor who smoked marijuana before stabbing a shipmate he thought was "out to get him."

But there was also a 1939 story that said cannabis raids by Anslinger's men "were carried out without fanfare or violence because marijuana users rarely, if ever, resist arrest." It seems "the drug usually leaves them in a torpor," and "the 'higher' an addict is with the drug the less bellicose he becomes." Reviewing Marihuana: America's New Drug Problem for the Times in 1938, Frederick T. Merrill (author of Japan and the Opium Menace) suggested a resolution to the apparent contradiction. "Depravity has been and still is the only motive for [marijuana's] habitual use, and its effects are particularly anti-social," he opined. "The reason why marihuana and crime are so closely linked is more understandable in view of the unpredictable reactions to varying quantities of the drug."

So was marijuana a "killer weed" that triggers mayhem and murder or a soporific drug that renders its users docile and indolent? Yes.

'The Ruinous Step From Marijuana to Heroin'

In 1945, a report commissioned by New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia concluded that "marihuana is not the determining factor in the commission of major crimes," that "marihuana smoking is not widespread among school children," that "juvenile delinquency is not associated with the practice of smoking marihuana," and that "the publicity concerning the catastrophic effects of marihuana smoking in New York City is unfounded." The Times quoted the reassuring findings, but the headline over the story correctly predicted that they would have no impact on policy: "Experts Discount Marijuana as Big Factor in Crime but Drive on It Will Be Pressed."

The La Guardia Committee Report, which was prepared by the New York Academy of Medicine at the behest of an advisory committee appointed by the mayor, irked Anslinger, who complained that it was unscientific. But having accomplished what he wanted with his horror stories about crimes caused by cannabis, the FBN head began to play down that angle. Now that the bureau had jurisdiction over the drug, hysterical reports about out-of-control marijuana addicts would not reflect well on it. Furthermore, as illustrated by Ethel Sohl's murder trial, the idea of cannabis-induced violence did not sit well with prosecutors, who did not want to see criminals escape responsibility by blaming their crimes on marijuana.

By the 1950s, Anslinger had backed away from his claim that marijuana turns people into murderers. Instead, he began arguing that it turns them into heroin addicts. The Times, in turn, began parroting the new rationale for marijuana prohibition.

A 1950 story cited "a sharp increase in dope addicts—victims who have 'graduated' from marijuana to heroin." It quoted Anslinger, who described the new heroin addicts as "young hoodlums" who "all started by smoking marijuana cigarettes." As he put it in congressional testimony the following year, "They took the needle when the thrill of marijuana was gone." A 1951 story described how "a youth tries a 'harmless' marijuana cigarette at a party" and later "takes the ruinous step from marijuana to heroin."

Marijuana's alleged role as a "gateway" helped justify lumping it together with other drugs in the penal code. In 1951, the Times reported that "Congress will be called upon shortly to consider a bill which experts believe will go further toward stamping out the narcotics evil in this country than anything since the Harrison Narcotics Act." The story was referring to the Boggs Act, which established mandatory minimum sentences for federal crimes involving marijuana and other illegal substances. According to Anslinger, the enhanced penalties—precursors to the draconian sentencing rules that in recent years have drawn bipartisan criticism—were necessary to win the "battle with the drug traffic."

While the Times first publicly toyed with the idea of ending pot prohibition in 1972, it did not get around to endorsing that policy until 2014. "Why not sharpen priorities by legalizing or at least decriminalizing marijuana?" asked a 1986 editorial. Good question.

Fifteen years later, the Times was still citing the purported link between marijuana and heroin as a reason to keep pot illegal. A 1966 editorial rejected psychedelic guru Timothy Leary's "specious" claim, following his 1965 arrest for marijuana possession, that freedom of conscience includes the freedom to alter your consciousness. "Experience has tragically demonstrated that marijuana is not 'harmless,'" the Times declared. "For a considerable number of young people who try it, it is the first step down the fateful road to heroin."

That claim was echoed several days later under the front-page headline "Drugs a Growing Campus Problem." Reporter John Corry allowed that "student pot parties, those wild abandoned orgies in which no man's daughter is safe, seem to exist more in fancy than in fact." Still, "a significant number of marijuana smokers will go on to heroin," he warned, citing the FBN. "'Potsville,' the narcotics agents say, 'leads to the mainline.'" Half a century later, in its editorial endorsing legalization, the Times would say "claims that marijuana is a gateway to more dangerous drugs are as fanciful as the 'Reefer Madness' images of murder, rape and suicide."

'The Dangers Appear to Be Less Than Previously Assumed'

Although the Gray Lady was not ready to let Leary off the hook in 1966, she was beginning to soften her stance. Three years later the Times urged Congress to "lighten the penalty for mere possession" of marijuana, which at the time carried a mandatory minimum sentence of two years. "The penalties for those who prey on the innocent by peddling drugs can hardly be too severe," another 1969 editorial said, but it urged "a distinction between soft and hard drugs."

By 1970, the year the Controlled Substances Act put marijuana in Schedule I, the law's most restrictive category, the Times was wondering whether the government should "continue to treat it in the same manner as heroin." It hastened to add, "This is not to say that marijuana should be legalized"—a policy that was supported by only 12 percent of Americans, according to a Gallup poll taken the previous year. Marijuana "is a dangerous drug," the paper explained in 1971, but not so dangerous that simple possession merits a prison sentence.

In 1972, reacting to the reformist conclusions of the Nixon-appointed National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, a Times editorial conceded "the dangers inherent in smoking marijuana appear to be less than previously assumed." It agreed with the commission that criminal penalties for possession and use should be eliminated. As for "outright legalization," the Times said, "the accumulation of further medical evidence might justify such a step later on." In 1978, the Times said marijuana "shows great, though not fully proven, potential as a therapeutic agent." But legalizing marijuana for medical use "would be premature," it said; more research was needed.

In 1996, responding to the passage of medical marijuana initiatives in California and Arizona, the Times was still calling for more research. In the meantime, it said, the Clinton administration's "aggressive campaign to combat the state initiatives…makes sense."

By then, the paper's position was at odds with public opinion. A large majority of Americans—69 percent, according to a 1997 ABC News poll—thought doctors should be able to prescribe marijuana for patients who could benefit from it. The crackdown the Times endorsed included an attempt to stop doctors from recommending marijuana by threatening to take away their prescribing privileges, a sanction that was ultimately rejected by a federal appeals court on First Amendment grounds.

In 2001, after a Republican replaced Clinton in the White House, the Times changed its tune. It condemned the new administration's "benighted efforts to prevent the use of marijuana to relieve the symptoms of pain, nausea or loss of appetite in desperately ill patients." After Barack Obama took over from George W. Bush in 2009, the Times praised his promise to leave state-legal suppliers of medical marijuana alone—a pledge that was soon broken by a crackdown more intense than Bush's.

The paper's reaction to the 2012 initiatives that made Colorado and Washington the first states to legalize marijuana for recreational use was less hostile than its initial response to medical marijuana in California. In late 2013, the Times noted the possibility that marijuana legalization could reduce traffic fatalities if it leads to less drinking. "That could be good news," it admitted. In January 2014, it marked the beginning of legal recreational marijuana sales in Colorado with a noncommittal editorial suggesting "what to watch for in the early stages of this experiment." It finally embraced legalization in July of that year.

In short, while the Times first publicly toyed with the idea of marijuana legalization in 1972, it did not get around to endorsing that policy until 42 years later. What happened in between?

Jimmy Carter, a president who advocated decriminalization of marijuana possession, was replaced in 1981 by Ronald Reagan, a president who ramped up the war on drugs despite his lip service to limited government. That crusade had the support of parents alarmed by record rates of adolescent pot smoking in the late 1970s. Gallup's numbers indicate that support for legalizing marijuana, after rising from 12 percent in 1969 to 28 percent in 1978, dipped during the Reagan administration, hitting a low of 23 percent in 1985.

'A More Sensible Alternative'

A story published in 1986 gives you an idea of how the Times covered marijuana during this period. The federal government had begun to cite the rising potency of marijuana as a reason parents who smoked pot in their youth with no ill effects should nevertheless be alarmed by the possibility that their kids might try it. Citing "parent groups and drug counselors," reporter Peter Kerr wrote that "a teen-ager's first brush with [marijuana] today may be a far more powerful experience than it was a generation ago."

To back up that claim, Kerr reported that the level of THC in samples seized by the government rose "from an average of 0.5 percent in 1974 to 3.5 percent in 1985 and 1986." But cannabis with a THC potency of less than 1 percent, commonly known as "ditchweed," is not considered psychoactive, so either pot smokers in the '60s and '70s only thought they were getting high, or there was something wrong with the government's samples from that period. Perhaps they degraded in storage before they were tested, or perhaps they were never representative of what people were actually smoking.

In other respects, however, Kerr's story was admirably balanced, especially compared to earlier coverage. Based on an interview with a spokesman for the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, he shared the argument that higher potency means less smoking, reducing the risk of respiratory damage. Kerr also reported that "recent studies…point to growing evidence that marijuana use may have serious long-term health effects" but added that "advocates of decriminalization of marijuana point to the lack of conclusive evidence that marijuana is more harmful than tobacco or alcohol."

That was an understatement, since there was (and is) strong evidence that both of those substances are more dangerous than marijuana, but it was still a welcome caveat. Kerr also noted that marijuana use by teenagers had declined since 1980 and that "debate continues about how harmful the drug is—and how vigorously laws against it should be enforced."

Legalization got a couple of positive mentions on the New York Times editorial page during the 1980s. A 1982 essay actually advocated "regulation and taxation" as "a more sensible alternative" to decriminalization, arguing that "a prohibition so unenforceable and so widely flouted must give way to reality." But that piece was attributed only to editorial writer Peter Passell, so it did not represent the paper's official position.

Four years later, an editorial that was mainly about drug testing asked, "Why not sharpen priorities by legalizing or at least decriminalizing marijuana?" Good question. Let's think about it for a few more decades.

The executive editor of the Times at this point, A.M. (Abe) Rosenthal, was a passionate prohibitionist who started writing a twice-weekly column for the paper in 1987. Although it was officially called "On My Mind," his detractors renamed it "Out of My Mind" because of its vitriolic, hyperbolic tone.

Rosenthal, who liked to argue that the war on drugs could not be said to have failed because it had never really been waged, deemed the idea of legalization "morally disgusting." In a 1989 column, he called opponents of drug prohibition "the new anti-abolitionists," a "scattered but influential collection of intellectuals" who were "intensely engaged in making the case for slavery." He railed against the legalization of medical marijuana, a "fraud" that he feared would "quickly make a mockery of the national consensus against drugs."

After the 1996 elections, Rosenthal castigated Bill Clinton for failing to "lead the fight against the near-legalization in California of marijuana, the proven gateway drug to hard drugs and mean deaths." He blamed the financial support of George Soros "and other folk whose own children are not likely to wind up in gutters, brains crippled by drugs."

In retrospect, Rosenthal's fulminations against drug policy reformers marked the beginning of the end for marijuana prohibition, which became steadily less popular during the next two decades. According to Gallup, support for legalization rose from 25 percent in 1995, the year before Californians approved medical use, to 58 percent in 2013.

"We have been careful and cautious on this subject," Rosenthal's son Andrew, then the paper's editorial page editor, told MSNBC after the Times finally took a stand against prohibition in 2014. The younger Rosenthal said the new position was not controversial within the editorial board and that when he raised the subject with the publisher, Arthur Sulzberger, "He said, 'Fine.' I think he'd probably been there before I was. I think I was there before we did it."

Rosenthal tells me he "never really did" discuss marijuana policy with his father, who died in 2006, because there "didn't seem much point to it, and we had lots of other things to disagree about." He adds that "his views were informed by misinformation that pervaded society for a generation, and he tended to lump marijuana in with all kinds of actually dangerous drugs."

It took more than a century for The New York Times to go from credulously accepting anti-marijuana propaganda to contemptuously rejecting it, along with the ban built on that foundation of lies. Which raises an obvious question: If the Times could be so wrong for so long about marijuana, how many other mistakes has it made in covering and commenting on drug policy?

The short answer is plenty. The paper has exaggerated the hazards posed by pretty much every substance that has ever been a subject of public concern while conflating the effects of drug use with the effects of prohibition. The corrections may take a while.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Reefer Madness at The New York Times."

Show Comments (68)