The European Union: Separating Myth from Reality

Despite its self-congratulations, the EU is not responsible for 60 years of peace and prosperity in Europe.

On Thursday, the British people will decide whether or not to stay in the European Union. The U.S. foreign policy establishment, President Barack Obama included, have urged the British to remain in the EU. The latter were not amused, noting that the United States does not care what the Europeans think when it comes to American relations with Canada and Mexico. So, in preparation for the British referendum on the EU membership, let us take a closer look at the EU: what is it and what has it accomplished?

This is how the EU answers those questions: "The EU is unlike anything else—it isn't a government, an association of states, or an international organization. Rather, the 28 Member States have relinquished part of their sovereignty to EU institutions, with many decisions made at the European level. The European Union has delivered more than 60 years of peace, stability, and prosperity in Europe, helped raise our citizens' living standards, launched a single European currency (the euro), and is progressively building a single Europe-wide free market for goods, services, people, and capital" (my emphasis).

This self-congratulatory assessment of the EU's achievements is deeply problematic. Consider peace and stability. The EU's narrative ignores, for example, the roles played by Germany's unconditional surrender, Anglo-American occupation of West Germany, the rise of the communist threat in the East, and the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization—all of which preceded the creation of the first and extremely tentative pan-European institutions. It also ignores the EU's failure to deal with the Yugoslav crisis in the early 1990s, which was eventually "resolved" by the application of American military strength.

Moreover, many Europeans see the EU as responsible for the growing instability in Europe. They see monetary policy as a source of friction between nation-states, with the relatively well-off Germany and Austria on one side, and the failing Greece and stagnating Italy on the other side. The same is true of the EU's failure to come up with an effective response to the recent wave of immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa, thus pitting the generally welcoming German government against the unwelcoming governments in Central and Eastern Europe.

Consider, also, prosperity. The role of the Marshall Plan in stimulating economic growth is, at best, controversial, but omitting it altogether from the EU's narrative of Europe's post-war recovery is self-serving. Similarly, Western European economies began to recover, as was to be expected, when the war ended and long before the signing of a free-trade agreement known as the European Economic Community in 1958.

That is not to say that intra-European trade liberalization was not beneficial. It was, beginning in the 1960s. (The last intra-European tariffs did not disappear until 1968.) In the meantime, Western Europe benefited from domestic reforms, such as Ludwig Erhard's liberalization of the West German economy in 1948, and the global reduction of tariffs under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which started in 1947. The official EU narrative tends to omit all of the above inconvenient facts.

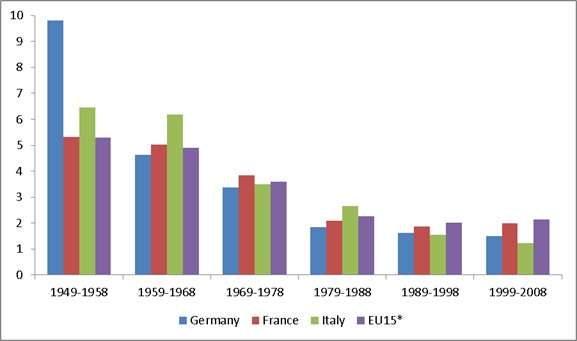

Figure 1: GDP, Average Growth per Decade, Percent (1949–2008)

That is not to deny the strong desire for peace and prosperity among European peoples and their leadership after World War II. Rather, as I argue in a paper that will be released by the Cato Institute tomorrow, the EU institutions were, for the most part, ineffectual, and have increasingly become liabilities. As the example of Switzerland shows, there is no a priori reason to think that a looser cooperation between European states, which would follow British withdrawal from the EU, is incompatible with peace and prosperity.

Show Comments (50)