Saving Earth's Biodiversity Through Markets and Technological Progress

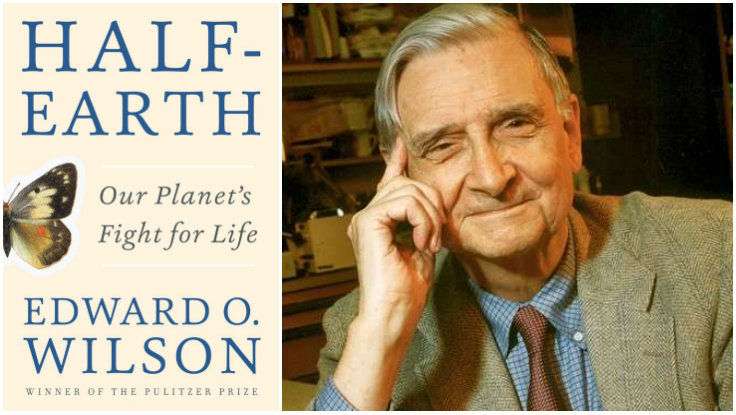

A review of Half Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life by Edward O. Wilson

Half Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life, by Edward O. Wilson, Liveright, 259 pages, $25.95

The world's greatest living naturalist, Edward O. Wilson, shares my conviction that economic, technological, and demographic trends point to a brighter future both for humanity and for the rest of nature. In his latest book, Half Earth, he sometimes comes off as practically a visionary transhumanist, predicting vast improvements by means of nanotechnology, biotechnology, and robotics. He even thinks that scientists will succeed at whole brain emulation—that is, the installation of human minds on digital devices—by the end of this century.

But that hardly means he has no worries. In Half Earth, he cites data showing that human activities, chiefly the expansion of agriculture and the introduction of species to new habitats, has likely raised the rate of species extinction considerably above the natural background trend. Recent research, he writes, "suggests species extinction rates at the present time are closer to one thousand times higher than that before the spread of humanity." Wilson urges us all "to adopt a transcendent moral precept" that states, "Do no further harm to the biosphere."

If the species extinction rate is this high, how many species are going extinct each year? Biologists estimate that the background rate of extinction without human influence is about 0.1 species per million species-years. This means that if you followed the fates of one million species, you would expect to observe about one species going extinct every 10 years. So far biologists have cataloged about 2 million species, but believe that many millions more remain to be discovered. Let's assume a moderate estimate of 5 million species.

If the extinction rate is now 1,000 times higher, that would mean that about 100 species are going extinct per million species-years. So if the world contains 5,000,000 species, that would suggests that 500 are going extinct every year. If that rate continued for the next 85 years, some 42,500 species would disappear by the dawn of the 22nd century.

Some researchers have suggested that species extinction will accelerate to 10,000 times the background rate. That would mean that 5,000 species would be going extinct per year, and 425,000 species—about 8.5 percent of the total—could be gone by the 22nd century. Most of the vanished species would be small creatures, such as insects, arachnids, worms, and so forth.

This is not the first time that biologists have sounded the alarm. For example, in 1980 the Global 2000 Report to the President predicted: "Extinctions of plant and animal species will increase dramatically. Hundreds of thousands of species—perhaps as many as 20 percent of all species on earth—will be irretrievably lost as their habitats vanish, especially in tropical forests." In his 1992 book The Diversity of Life, Wilson himself made the "cautious" calculation that "the number of species doomed each year is 27,000. Each day it is 74, and each hour 3."

That did not happen. In 2007, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) calculated that humanity had "forced 869 species to extinction" since 1500. On the other hand, the IUCN estimated that nearly 17,000 plant and animal species are currently threatened with extinction.

Let me be clear: I mourn the loss of species. The creatures currently inhabiting this planet have made it through the brutal natural selection sieve (and asteroids and volcanic eruptions) that destroyed over 99 percent of all species ever to have existed on Earth. Each embodies complex genetic libraries, behavioral repertoires, and evolutionary histories that are both scientifically fascinating and aesthetically fulfilling. As a relatively well-off first-worlder, I have had the intense pleasure of walking in the wild within 40 feet of grazing rhinos and of swimming with Galápagos penguins. It would be a shame if future generations do not have an opportunity to enjoy such experiences.

One area where Wilson goes wrong is his forceful rejection of the notion of the Anthropocene, defined as the new era in which humanity is the dominant force on Earth. He particularly loathes the researchers who urge their colleagues to accept the end of "pristine" wild lands and instead investigate the "novel ecosystems" that humanity is busily creating by moving species around the planet. Wilson points out that introduced species are sometimes a threat to native species. Species that evolved in isolated ecosystems on oceanic islands and freshwater streams are especially vulnerable. For example, a 2013 study estimated that Polynesian wayfarers with their rats and pigs caused the extinction of 1,300 species of birds as they spread across the uninhabited Pacific archipelagos.

Clearly some invasive species have caused considerable damage, especially disease organisms like the fungus that wiped out the American chestnut and the one that is currently assaulting amphibian species around the globe. Nevertheless, human-introduced species do seem generally to be increasing the species richness and perhaps even improving ecosystem functions, such as nutrient cycling, in many new habitats. For example, New Zealand's 2,000 native plant species have been joined by 2,000 from elsewhere since the arrival of European settlers, doubling the plant biodiversity of its islands. Chris Thomas, a biologist at the University of York, suggested in 2015 that plant speciation has actually sped during the Anthropocene and that the current "plant speciation rate could be comparable to the extinction rate."

Wilson regards such Anthropocene musings as "the product of well-intentioned ignorance" and pleads for biology to restore many ecosystems to pre-modern or even pre-human-interference baselines. He may be in luck. Researchers using the fantastic new CRISPR gene-editing technology have devised gene drives that can curate plant and animal populations in the wild. To extirpate invasive rats from a Pacific island, researchers could create a gene drive that will insure that all rat pups are born male. Notionally speaking, such gene drives could rid New Zealand of the 2,000 non-native plant species that have taken up residence there.

In Wilson's larger vision, he wants to "increase the area of inviolable natural reserves to half the surface of the Earth or greater." This proposed set-aside is based chiefly on Wilson's seminal work on species area curves, which roughly estimates that reducing the area of a habitat by 50 percent will still enable about 90 percent of its species to survive. About 15 and 2.8 percent, respectively, of the Earth's land and oceans areas are now in protected reserves of various sorts. Wilson wants to create more reserves "within which natural processes unfold in the absence of deliberate human intervention, where life remains 'self-willed.'" He thinks many favorable trends will make this possible sooner rather than later.

The first favorable trend is that human population will very likely peak before the end of this century. Urbanization, economic growth, and the education of women all contribute to this trend. Wilson forecasts human population to peak at around 11 billion by the end of the century, and other researchers think the peak will be much faster and lower—perhaps 8.7 billion by the middle of this century. Another highly positive trend is that 80 percent of people will live in cities by then. Currently, about half the world's population lives on the landscape, mostly as hardscrabble farmers. With urbanization, rural populations will be cut in essentially half, dropping from 3.6 billion now to 1.7 billion in 2050. This frees up lots of land for nature.

Wilson also wants a new "green revolution" to dramatically boost crop yields, so that more land can be returned to a natural state. Again, the news is good: Jesse Ausubel, a researcher at Rockefeller University, calculates that we are on the verge of peak farmland. An area nearly double the size of the U.S. east of the Mississippi could be restored to nature by 2060.

Wilson expects humanity's ecological footprint—that is, the amount of land and resources used to support people—will also shrink radically. "The footprint will evolve, not to claim more and more space, as you might at first suppose, but less," argues Wilson. "The reason lies in the evolution of the free market system, and the way it is increasingly shaped by high technology." Market signals relentlessly push entrepreneurs to find ways to do more with less. Thanks to intensive economic growth, Wilson predicts, the "average person can expect to enjoy a longer, healthier life of high quality yet with less energy extraction and raw demand put on the land and sea." This growth will be enabled by a combination of nanotech, biotech, and robotics. Wilson also believes that whole brain emulation will spark an intelligence explosion that will further enable humanity to withdraw from nature.

At the end of my book The End of Doom, I wrote:

New technologies and wealth produced by human creativity will spark a vast environmental renewal in this century. Most global trends suggest that by the end of this century, the world will be populated with fewer and much wealthier people living mostly in cities fueled by cheap no-carbon energy sources. As the amount of land and sea needed to supply human needs decreases, both cities and wild nature will expand, with nature occupying or reoccupying the bulk of the land and sea freed up by human ingenuity. Nature will become chiefly an arena for human pleasure and instruction, not a source of raw materials. I don't fear for future generations; instead, I rejoice for them.

Our views may not be completely congruent, but I am delighted to find that Edward O. Wilson largely agrees with that conclusion.

Show Comments (32)