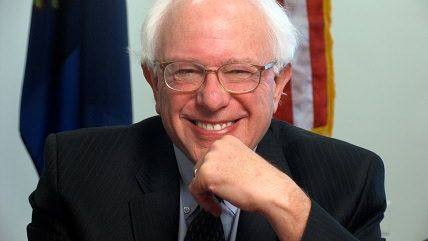

Why Bernie Sanders Is Wrong About Private Prisons

Closing private correctional facilities would make life worse for prisoners and taxpayers.

Last week, Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) joined three House Democrats in introducing criminal justice reform legislation—the "Justice is Not For Sale Act of 2015"—that includes provisions banning the use of all private prisons by federal, state and local governments within two years.

Setting aside that this is likely a political nonstarter in the current Congress, it should also be a policy nonstarter too. The proposed private prison ban is the sort of pandering pablum that may appeal to Sanders' progressive, anti-corporate base, but it confuses symptom with disease and would have little impact on lowering incarceration rates nationwide. In fact, it would be more likely to raise the costs of corrections by returning prisons to government monopoly control and, worse, increase overcrowding in public facilities.

As German Lopez helpfully pointed out in a recent Vox explainer, for all the outsized attention that private prisons receive in the media and in criminal justice policy debates, they only hold a tiny fraction of the total federal and state prison population. According to Reason Foundation's Annual Privatization Report 2015, private prisons housed 141,921—or a paltry 9 percent—of the total 1.57 million federal and state inmates in 2013.

While that's up from 6.5 percent in 2000, it still hovers in the single digits and may have reached a plateau; the private prison share has remained relatively consistent since the total federal and state prison population peaked in 2010.

Lopez notes that given these small numbers, private prisons "don't hold a lot of sway over the whole system," but that "it's good politics" for Sanders to try and appeal to the parts of his base that believe that private prisons somehow caused mass incarceration, not the other way around. In reality, the growth of the private corrections industry has been a response to the tough-on-crime, lock-em-up policies that took hold in the 1970s and 1980s (a point Lopez details further in his piece).

To be fair, Sanders even acknowledged these small numbers in a recent press release, yet still claims a private prison ban would be a "good step forward" to reforming a broken criminal justice system. What's left unexplained is how banning those that operate 9 percent of the system will make any dent whatsoever in improving outcomes for the remaining 91 percent.

It might just do the opposite.

Take California as an example. Already stressed public prison systems in states like California—which alone accounted for one of every 13 inmates held in private prisons in 2013—would need to absorb thousands of inmates into overcrowded government-operated prisons. In fact, California ramped up its use of private prisons in the late 2000s as part of a strategy to reduce chronic overcrowding in state-run facilities and comply with a federal mandate to reduce the state's total prison population.

Left unanswered is why Sanders believes that the answer to reducing prison overcrowding is to potentially create more of it, and why it is the federal government's prerogative to overrule states' decision making on how to manage their own prison populations. (As an aside, also note the irony of a progressive like Sen. Sanders seeking to undermine a progressive state like California's work to improve conditions in its prison facilities by reducing criminogenic overcrowding.)

And while there has been a long-running policy debate over the cost-effectiveness of private prisons, with conflicting evidence on both sides, it's safe to assume that in at least some cases, the costs of in-house operation could be significantly higher than in contracted facilities, especially when pension, retiree healthcare and infrastructure costs are taken into account. Rather than inmates, the beneficiaries of a private prison ban would really be public sector correctional officers and the unions like California's CCPOA that represent them.

Further, while focusing on the use of prison contracting by federal agencies may be an appropriate topic for congressional debate, using federal legislation to unilaterally break dozens—if not hundreds—of state and local prison contracts would constitute a blow against federalism and would no doubt raise the ire of state and local politicians who entered into their contracts in good faith. Just because the U.S. Constitution's Contracts Clause does not expressly forbid the federal government from impairing existing contracts doesn't mean that it makes sense to do so.

Certainly, some private prison opponents will worry about private prisons being less safe for inmates or that companies might lobby for more people to be incarcerated. On the former point, notwithstanding recent events in places like Oklahoma and Arizona, the overall track record for incidents in private prisons tends to be comparable to government-run prisons. After all, prisons are difficult environments, and bad things happen even in well-managed prisons, public or private.

There's a key difference, however, between privately run prisons and government-run counterparts: the contract mechanism, which provides a vehicle for accountability. If dissatisfied with performance, a government can cancel a prison contract with a private company. By contrast, the government tends not to fire itself, and the watchmen ultimately watch themselves.

On the latter concern, while claims that private prison companies have directly lobbied to lock more people up tend to be based largely on innuendo, government prison guard unions have routinely done so.

In critiquing Sanders' proposed private prison ban, Fordham Law School professor John Pfaff makes an astute observation that "[b]y focusing on 'private!' not 'incentives!' Sanders is emphasizing form over substance."

This is especially true when one considers that we are in the early stages in a major rethinking of how correctional contracts can be designed and harnessed to better target redicivism reduction and offender rehabilitation, both cited by Sanders as motivations for reform. As some quick examples:

- In 2013, Pennsylvania cancelled all of its contracts with private operators of community corrections centers and rebid them on a performance basis, tying vendor compensation to their performance at reducing recidivism rates among the populations they manage. The state corrections agency recently announced an overall 11.3 percent reduction in recidivism across its 42 contracted community corrections centers between July 2014 and June 2015, marking the second consecutive year of decline.

- That same year, Pennsylvania awarded a five-year correctional mental health services contract that was updated to significantly enhance performance expectations, including financial incentives to reduce the number of misconducts for mentally ill offenders, the number of inmates recommitted to prison mental health units, and the number of recommitments to prison residential treatment units. Conversely, the state can impose financial penalties on the contractor if it fails to achieve targeted baseline results for those same metrics.

- The U.K. has piloted similar recidivism-based, pay-for-success contract models for prison operations in recent years.

- A number of pay-for-success (or "social impact bond") contracts have been implemented in Massachusetts, New York State, New York City, the U.K., and elsewhere to provide private-sector sector financing and nonprofit delivery of inmate programming aimed at reducing reoffending among those nearing release from prison.

The common theme here is that rather than avoiding a private sector role in corrections, forward-thinking jurisdictions like Pennsylvania and the U.K. have accepted the fact that after roughly 30 years in existence, the private corrections industry is here to stay. Hence, rather than wishing the industry away as the Sanders crowd would prefer, the more pragmatic view is to try to make better use of privatization and focus the contracts (and the economic incentives underlying them) toward moving the needle on the persistent challenge of recidivism.

Put simply, rather than abolishing private prisons altogether, why not incentivize the private sector to step up and do a better job on recidivism reduction than governments are doing themselves?

While the experimentation with various performance contracting models aimed at reducing recidivism is still in a nascent stage—and the ability to scale up successful models thus remains uncertain—placing rehabilitation and recidivism reduction at the core of the correctional contracting model has the potential to accelerate the discovery of successful programs and innovations more than hoping governments bound by inertia and budget constraints will somehow overcome those challenges and reverse decades of poor performance on recidivism.

Instead of pursuing a quixotic quest to ban private prisons, Sanders would do far better to concentrate on some of the other elements of his proposed criminal justice legislation, including reinstating federal parole and changing federal policies on immigrant detention. Over at Fusion, Jorge Rivas accurately notes that "[i]t may be easier for Sanders to change the laws that incarcerate immigrants than actually closing the privately run immigration facilities that detain them."

In short, contracts follow the policies, not the other way around. And there's no shortage of other, more substantive criminal justice reform proposals on the table for Sanders to engage (examples here and here, for starters).

Until then, those of us interested in advancing real criminal justice reform should not get distracted by hollow, ineffective proposals like Sanders' proposed private prison ban.

Show Comments (50)