Suspicious Minds

The '70s saw a strange interplay of skepticism and nostalgia.

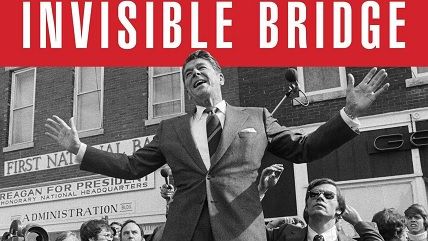

The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan, by Rick Perlstein, Simon & Schuster, 856 pages, $37.50

As the Watergate scandal exploded and Richard Nixon's hold on the presidency started to slip, one group stood steadfast in its commitment to the man in the West Wing. Its members took to chanting "God needs Nixon" outside Congress' Rayburn Office Building. At the 1973 White House Christmas tree lighting ceremony, over a thousand of them showed up to pay their respects. When the president emerged to greet the throng, Garry Wills later reported in Harper's, "they knelt down to worship him."

They were Moonies.

The 1970s were a time of decay for traditional forms of authority, from the president in the White House to the parent in the home. In the resulting void, dozens of would-be alternatives offered substitute certainties, from a flurry of peculiar self-help movements to the strange new religions whose critics called them cults. The Moonies—a dismissive nickname for the followers of Rev. Sun Myung Moon's Unification Church—belonged to one of the most infamous young faiths. The fact that the president was leaning on them for support summed up just how jumbled American attitudes toward authority had become.

The Moonies' appearance at the White House is just one small but telling anecdote in a volume stuffed with such stories. The Invisible Bridge, the third entry in Rick Perlstein's absorbing series of books on recent American history, devotes over 800 pages to an interval of just three and a half years, beginning with Nixon's 1973 claim to have reached "peace with honor" in Vietnam and ending with Ronald Reagan falling just short of the Republican nomination in 1976. In between, it covers not just the obvious episodes—the Watergate scandal, the fall of Saigon—but smaller moments, deeper social trends, and illuminating cultural artifacts, from the early episodes of Saturday Night Live to the fiction of Judy Blume. It is probably the only book where a revolution in sexual mores is discussed in a chapter called "Sam Ervin," and it is surely the only book that makes that combination work. At times it feels less like a '70s history than a '70s movie: one of those Robert Altman pictures with an enormous cast, multiple interwoven storylines, overlapping dialogue, and a climax—in this case, the 1976 GOP convention—where petty personal squabbles and world-changing decisions share center stage.

In Perlstein's telling, the two great currents of the time were suspicion and nostalgia, a skepticism toward American institutions and a yearning for American innocence. "There were two tribes of Americans now," he writes. "One comprised the suspicious circles, which had once been small, but now were exceptionally broad, who considered the self-evident lesson of the 1960s and the low, dishonest war that defined the decade to be the imperative to question authority, unsettle ossified norms, and expose dissembling leaders." The other tribe "found another lesson to be self-evident: never break faith with God's chosen nation."

He's partly right. Americans in the 1970s were indeed torn between a drive to question authority and a longing for an authority they could believe in. But the evidence in Perlstein's own book shows how hard it is to divide those forces into two distinct tribes. Suspicion and nostalgia were woven up with one another, tangled so tightly that they might be inseparable. Even a nostalgist might need a suspicious story to explain how things had gone wrong. And even a skeptic might believe that the country had once been on the right path, that progress required us to turn back the clock.

Like many histories, Perlstein's book offers readers a sort of double vision. On one hand, he shows us the past through the eyes of the future, letting our hindsight reveal truths that contemporaries missed. One lesson of the book, for instance, is how frequently people underestimated Ronald Reagan. Time and again, we see someone pronouncing the man's career over, only to be surprised when he not only survives but leaps ahead. (In the book's very last line, quoting an article published four years and three months before Reagan was elected president, The New York Times pronounces him "too old to seriously consider another run at the Presidency.")

At the same time, the book lets us see the past through the eyes of the past, reminding us of the often enormous gulf between how an episode appears today and how it appeared as it was transpiring. Sometimes this is just a simple matter of reminding us that historical events that now seem like separate stories in fact happened simultaneously, and that they were experienced that way by the people who lived through them.

For example: Any good history of Watergate will tell you that Nixon's resistance to cooperating with Congress produced a constitutional crisis. Many will mention that there were prominent, mainstream Americans who seriously feared we were on the verge of a turn toward fascism. (Watergate "could serve as a dress rehearsal," one New York Times writer declared, "for an American fascist coup d'etat.") But they generally will not mention that, in the midst of those fears, Nixon made a televised speech that called for shared sacrifice, renewed national purpose, "the strength of self-sufficiency," and emergency legislation.

That is because he was speaking about the energy crisis, and we today think of oil and Watergate as separate subjects. But if you were a skeptical American in 1973, it was natural to suspect that the president was trying to distract you from his scandal—especially when, as Perlstein notes, the immediate situation wasn't as urgent as Nixon made it sound. And it was natural to be uneasy about calls to sacrifice and unity from a president who seemed to be teetering on the brink of breaking the constitutional compact. If you've wondered why not just many conservatives but some prominent progressives, such as the civil rights leader Jesse Jackson, declared the energy crisis a hoax, this is one place to start.

Again and again, Perlstein juxtaposes stories like this, sometimes spelling out the connections and sometimes just being suggestive. Periodically he'll simply break into a rapid montage of scary headlines. One paragraph leaps from the Patty Hearst kidnapping to the "Zebra" serial killings to the nearly simultaneous outbreak of six tornadoes; the paragraph after that swings through six more stories, peaking with a Playboy feature headlined "The Devil Made Us Do It: A Ten Page Pictorial on the Occult." Some of these events had a major social impact and some of them did not, but together they feel like an apocalyptic tide.

It is possible to complain—as Sam Tanenhaus did, reviewing the book in The Atlantic—that you could concoct such a storm with headlines culled from many periods of American history. But from the perspective of the people within that apocalyptic tide, that hardly matters. This was how it felt in the moment; just then, the world seemed to be a dangerous chaos. If it had seemed the same way in the past, well, those former feelings of dread were largely forgotten. Like I said, it was a time of nostalgia.

For Perlstein, Reagan embodies nostalgia, because Perlstein's Reagan is constantly rewriting his own history, revising his past to bring it into accord with the way he wanted the world to be. This isn't exactly unusual behavior for a politician. Indeed, The Invisible Bridge makes a good case that Jimmy Carter was guilty of the same thing. But Reagan did have a special talent for it.

Perlstein does a good job of undermining some of the legends that have attached themselves to Reagan. Reagan famously said, for instance, that he became a Republican because the Democratic Party had gotten too liberal—in his oft-quoted words, "I didn't leave the Democratic Party, the Democratic Party left me." Perlstein points out that Harry Truman's proposal for national health insurance was well to the left of John F. Kennedy's proposal for Medicare, yet Reagan happily backed Truman in the '40s before he condemned Medicare as socialized medicine a decade and a half later. Clearly the man's views had changed, even if he preferred to believe that he had stood still while the Democratic Party fell from grace. Perlstein offers a plausible account of how Reagan's opinions evolved, putting particular stress on the future president's stint in the 1950s and early '60s as "roving ambassador" for General Electric. In those days, Perlstein notes, G.E. devoted a lot of resources to making a moral case for capitalism.

Perlstein doesn't mention it, but the company had just gone through an ideological shift of its own. In the 1920s, G.E. President Gerard Swope unsuccessfully invited the American Federation of Labor to organize his company, hoping to establish a predictable relationship with a single industrial union rather than battling a wide array of craft unions that each had its own interests and demands. During the Depression, Swope devised an economic stabilization plan that helped inspire Franklin Roosevelt's National Industrial Recovery Act; he also advised Roosevelt while the president was developing his Social Security proposal. G.E.'s politics in this era were centered around the idea of state-corporate cooperation, with a secondary role for suitably submissive unions.

Then a wave of strikes in the '40s changed the corporate mood, souring its view of organized labor and at least certain sorts of government intervention. Under the guidance of Lemuel Boulware, the firm's new labor-relations man, G.E. was soon distributing literature ranging from a comic-book adaptation of F.A. Hayek's The Road to Serfdom to a conspiracy tract by the liberal-turned-McCarthyist muckraker John T. Flynn. Reagan the former Trumanite absorbed these influences, and their effects on his worldview were soon felt.

In a detail that says a lot about both G.E. and Reagan, the future president got in trouble with the company after he took to criticizing the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). The agency bought its turbines from G.E., you see. After an awkward meeting with the company's CEO, Reagan agreed to drop the TVA references from his speeches. This quiet change had no impact on his reputation. Like many politicians, Reagan had a knack for appearing to be uncompromising as he compromised.

Perlstein argues that he also had "the gift of moral absolution": an ability to turn tales of trauma into tales of redemption, allowing Reagan to project a faith in American goodness at a time when many people were calling that goodness into question. This "blithe optimism in the face of what others called chaos," Perlstein writes, was "what made others feel so good in his presence—and what drove still others, those suspicious circles for whom doubt was the soul of civic wisdom, to annoyed bafflement at his success."

On one level, this is exactly right: Reagan did frequently frame his stories this way, and that does explain a part of his popular appeal. But on another level, it is incomplete. Reagan also found ways to tap into the very skeptical spirit that he was defying.

And that brings us back to the complex relationship between suspicion and nostalgia.

Those "suspicious circles" who despised Reagan were prone to nostalgia for past presidents, particularly JFK. Perlstein quotes a kindergartener contrasting Kennedy with Nixon—"There used to be a president who didn't lie, but he's dead!"—and he demonstrates that the boy's rosy view of the 35th president wasn't limited to schoolchildren. For many Americans, Perlstein writes, "'Kennedy' meant comfort, truth, trust, the calm before the storm."

That sentiment extended deep into otherwise skeptical segments of society, from countercultural filmmakers to anti-CIA crusaders. (Frank Church, the Idaho Democrat who headed the Senate's probe into the crimes of the intelligence community, tried hard to resist the conclusion that Kennedy had been complicit in much of the misbehavior.) The conspiracy theories that blamed the U.S. government for JFK's death may have been some of the most extreme expressions of the era's suspicious spirit, but they tended as well to be suffused with this nostalgic idea that there once was an innocent president whose death had put the country off track. The typical assassinologists believed, Perlstein writes, "that if they could simply expose the lies of the powerful who covered up the veritable regicide, they could bring redemption to a fallen land."

Meanwhile, the right wing absorbed a lot of the period's skeptical spirit. It's telling to compare the conservative movement's reaction to Watergate with the response among Washington's mandarin class. The Georgetown villagers fretted about the scandal's impact on how the public perceived the presidency; each time a new revelation emerged, they moved to contain it, just slightly expanding the size of the infection that would need to be excised before the establishment could return to business as usual. Conservatives, by contrast, adopted a slash-and-burn everybody-does-it defense of Nixon that rivaled the assassinologists' vision in its portrait of Washington as a fetid swamp—except the conservatives didn't have a soft spot for anyone named Kennedy. "If Nixon's guilty, then so were Johnson and Kennedy and Eisenhower and Truman," announced one of Nixon's most notorious last-ditch defenders, a retired rabbi named Baruch Korff. "And, my God, I could tell you things about Roosevelt!"

When people like Korff said things like this, it was a cynical exercise: not an attack on official corruption so much as a resentful whine that Nixon was being singled out. But even in those cases, that meant the faction most inclined to excuse abuses of power was now going out of its way to highlight abuses of power. The most prominent person to follow this script was the Nixon speechwriter turned New York Times columnist William Safire, who took a strong interest in Kennedy-era malfeasance. (Unlike Korff, Safire was capable of criticizing his old boss Nixon too, particularly when the president's abuses came close to home. In 1973, on learning that the FBI had tapped his phone on the White House's orders, he devoted a column to his "fury" at the "unconscionable invasion.")

The document that best encapsulates this attitude is probably Victor Lasky's 1977 book It Didn't Start with Watergate. Lasky's political sympathies may be inferred from the fact that he once received a grant of $20,000 from that fountainhead of Watergate crimes, the Committee for the Re-Election of the President. But as he took his reader on a tour through the misdeeds, some imagined and some very real, of Presidents Roosevelt, Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson, he wound up painting a portrait of a deeply stained political establishment. At one point he approvingly quoted Noam Chomsky. Skepticism makes strange bedfellows.

More broadly, the right's rhetorical jabs at big government were custom-made for a skeptical age, even if some of those same conservatives turned around and defended big government when it manifested itself as the CIA, the FBI, or the Nixon White House. And social conservatives sometimes aimed their fury not just at the elites but at American society at large. (The rising anti-abortion movement, Perlstein notes, believed that "a society gone mad was sanctioning genocide." No innocence there.) They may have yearned for certainties, but so did the Kennedy nostalgists on the left. In both cases, the longing for innocence was embedded in the skepticism.

That skepticism and that yearning were affixed so tightly together that Perlstein occasionally errs when deciding which is which. He presents nuclear energy, correctly, as an institution that attracted popular suspicion in the '70s. Resistance to the metric system, meanwhile, appears here as an example of nostalgic Americans "hugging any excuse not to change." But one of the most prominent opponents of metric conversion was Whole Earth Catalog founder Stewart Brand, a hero for many in the more left-leaning suspicious circles. Doing a victory lap in New Scientist after it became clear that metric conversion was a flop, he compared metrification directly to nuclear power, declaring that both "sound terrific so long as you don't think about them for more than 30 seconds."

When suspicion and innocence are wound together, successful politicians learn to draw on both sentiments at once. Two figures were particularly adept at this: Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan.

When Carter and his all-things-to-all-people campaign emerged in the 1976 primaries, he regularly hit the evils of the '70s scandals in particular and government in general. But his rhetoric distinguished the citizens from the state. You were still innocent, he told the country, even if your leaders weren't. If you sent him to Washington, he said in a famous phrase, he'd give you "a government as good as its people."

Reagan, unlike Carter, wasn't prone to invoking Watergate as a sign of the state's misdeeds. He had, after all, stood by Nixon to the end. Yet he fed on people's distrust of power even as he reassured them. Entering the Republican primaries in late 1975, he condemned Washington's "buddy system" of corruption and privilege; the old G.E. spokesman even threw in a jab at "big business." His willingness to take this approach had its limits—at the same event, he dodged a question about the FBI's surveillance of Martin Luther King. But like Carter, he was attempting to appeal to both the public's skepticism and the public's nostalgia, its fear of the powerful and its desire to believe that the voters themselves, far from the Beltway, were untainted by the evil in D.C.

Neither Carter nor Reagan invented that synthesis. The idea of an essentially noble people facing a corrupt establishment has been the default narrative for more than a century's worth of populist crusades. Maybe more significantly, given Reagan's Hollywood background, it's the worldview you'll find in many Frank Capra films. People who invoke Mr. Smith Goes to Washington as a tribute to the American way forget how dark the movie's portrait of American political culture actually is; Jimmy Stewart, in the title role, is practically the only honest man in the city. Mr. Smith goes to Washington, finds it soiled with corruption, reaches back to Lincoln and Jefferson for inspiration, and wins a victory that redeems American democracy. It's an appealing script, and politicians love to let voters imagine that they're reenacting it.

Jimmy Stewart shows up a few times in The Invisible Bridge. In his final cameo, we see him stumping for Reagan on the campaign trail. (As endorsements go, that sure beats the Rev. Sun Myung Moon.) Perlstein notes that Stewart spoke in "his best aw-shucks Mr. Smith tones." A baton was being passed; a new actor was taking an old role.

Show Comments (17)