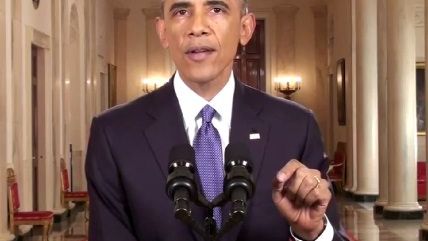

Obama's Immigration Order Means Rational Use of Deportation

The president is right to think the law should not function like a lottery.

If you're a foreigner in this country without authorization, you may be a hardworking, upright and taxpaying person, but you live in daily terror of making a fatal misstep. Overlooking a broken taillight, being a witness to a crime, getting hit by a car while crossing the street—minor misfortunes that attract the attention of police can bring exile, family breakup and misery.

Yoli Navas, a college student in Boston, came to the United States from Venezuela at the age of 6. She was one of the lucky "Dreamers" spared by President Barack Obama's 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) for more than a million young people brought here without permission by their parents. But she faced other perils.

"Those of us who are fortunate enough to still have our parents here live in fear every single day," she wrote last year on the blog of America's Voice, a pro-immigration group. "If my parents are deported, I would either be left without a family, or I would be the sole caretaker of my 13-year-old and 11-month-old sisters.

"This could mean being separated from my family for years, or having to drop out of school just to be able to take care of my sisters. If I had to drop out, that would mean I would no longer be eligible for DACA, which would lead to my deportation as well."

Under Obama's new executive order, up to five million undocumented immigrants could gain work permits and an assurance they won't be removed. This group includes the parents of kids born in the United States as well as foreigners who have been here five years or more without getting into serious trouble. Navas' parents would qualify. So for two years, anyway, their mind and hers will be at ease.

Obama's argument is that since the federal government can't and won't expel everyone who is here without authorization, it should pass over those who pose no real threat and focus on the more objectionable ones—criminals and foreigners who return after being expelled.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has the manpower and money to deport only about 4 percent of the foreigners who are not entitled to be here. It makes sense to focus those resources on the most worrisome ones.

Critics who opposed Obama's previous reprieve, however, are even more vehement in opposing this one. They regard it as an unconstitutional abdication of his duty to enforce the laws. Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Tex., said Obama was "acting as a monarch."

It's not a ridiculous claim, but it falls short of being persuasive. The Supreme Court has ruled that in this realm, the executive branch has plenty of latitude. "A principal feature of the removal system is the broad discretion exercised by immigration officials," it said in 2012. "Returning an alien to his own country may be deemed inappropriate even where he has committed a removable offense or fails to meet the criteria for admission" (emphasis added).

Obama hasn't helped his cause by repeatedly insisting that he didn't possess this authority before suddenly deciding, on the advice of lawyers, that he does. But it's reasonably clear that the powers used by Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush in shielding some immigrants also cover what Obama is doing.

The difference between this new approach and the previous one is modest as a matter of federal policy. Its impact on the lives of those affected, though, is huge. Under previous rules, the vast majority of undocumented foreigners would not, in fact, be deported in the next two years. ICE can't handle most of them. But they would all be at perpetual risk—a small risk of a terrible outcome.

Obama's directive isn't likely to reduce the number of people who will be removed during his remaining tenure. It merely defines the group from which these deportees will be chosen. The change is important for the small number of affected immigrants who otherwise would be expelled. But it's even more important for all the others who can stop worrying about that fate, at least for the time being.

Under this program, deportation would be used in a rational way against those most deserving of removal. Under the GOP alternative, the number wouldn't be much different, but being expelled would be mostly a matter of terrible luck. Obama's critics can live with that sort of random eviction. But the president is right to think the law should not function like a lottery.

Show Comments (157)