The Case For a Military Too Small for Obama (Or Any President) To Abuse

If you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail. If politicians have a whole bunch of Tomahawk missiles, they look for places to put craters.

An old saying has it that when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail. It's probably fair to say that when you have a honking huge military machine, everything looks like…Kosovo? Iraq? Afghanistan? Libya? Syria? Well, a handy target for some expensive ordnance, anyway. If you want everything to stop looking nail-ish, it's a good idea to put that hammer away. And if we want Syria—let alone the next target of opportunity—to stop looking like the latest good place for the U.S. to install new craters, we probably need to reduce our military's ability to reach around the world at will.

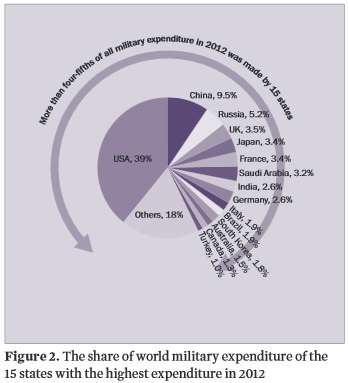

Over the 10 years between 2001 and 2011, acccording to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, annual U.S. military expenditures rose, in constant 2010 dollars, from roughly $385 billion to $690 billion, and from three percent of GDP to 4.8 percent. SIPRI's definition of such expenditures is more inclusive than some governments use, and so perhaps a tad more eye-popping (and honest) than most officials like, since they tend to emphasize "defense budgets" and downplay military aid and the often off-budget costs of actual operations. That means other numbers float around out there, military spending-wise, but these are good numbers with which to start and they can be compared across nations.

And what a comparison!

In 2012, the United States was responsible for 39 percent of the world's total military expenditures (PDF). That's actually down a hair, percent-wise, since the fall of the Soviet Union left the U.S responsible for more than 40 percent of world military expenditures. Hey, somebody had to fill the vacuum. But it's still more than the next 10 countries combined.

That kind of spending on guns, planes, missiles, ships and troops buys a huge can of whup-ass, and the U.S. hasn't been reluctant to use it. Granted, 9/11 called for some sort of response against Al Qaeda and its Taliban protectors, so we invaded Afghanistan. Then we invaded Iraq because… Well, apparently because…elusive weapons of mass destruction? Supposed sponsorship of terrorism? General dislike of the local tyrant? Take your pick.

Eight years later, even the Iraqi puppet government we'd installed had tired of its uninvited guests. It denied legal immunity to the remaining troops, effectively closing the door on the occupation, though only after the deaths of 4,804 coalition (mostly American) troops and a heartbreaking number of Iraqis, though the actual number may never be known.

Troops remain in Afghanistan, though the Taliban government that sheltered Al Qaeda has long since been replaced with something predictably corrupt, though less threatening to the American people than its predecessor. Coalition forces there have lost 3,371 lives (and counting), about two-thirds of which are American. Civilian casualties in that country rank in the thousands, both from insurgents and from occupation forces.

Iraq and Afghanistan have occupied most of the public's attention, military action-wise, over the past decade—logically enough, since they've been the primary sources of Americans in body bags—but U.S. military might has had its lethal way elsewhere, too. Notably, American forces, largely in the form of Tomahawk missiles, participated in an international effort to replace Libya's lunatic dictator with whatever is going on in that country now.

In these image-sensitive days, much U.S. military action is carried out by killer robots raining death from the skies. Fewer body bags come home that way, though there are plenty on the receiving end. Columbia University's Human Rights Clinic estimates that up to 155 Pakistani civilians (PDF) were killed by drones in 2011 alone. CIA drones reportedly stick around after the first hit to blow up whoever shows up to help.

Aside from chasing the Taliban and its Al Qaeda buddies out of Afghanistan, sort of, it's difficult to see what the U.S. has gained from all of this invading, shooting and detonating. Well, other than a percentage of the world's population phobic about buzzing noises in the sky, ever-more unkind thoughts about the United States, and a huge burden on U.S. taxpayers who foot the bill for these bloody adventures, that is.

Those costs, in lives and money, will only go up with any action against Syria. Americans seem to know that, because poll after poll overwhelmingly shows public opposition to military action in that country.

But all of these military incursions are possible only because an enormous military apparatus begs to be used by the sort of people—politicians—who aren't known for self-restraint. As former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright said to then-chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Colin L. Powell, "What's the point of having this superb military you're always talking about if we can't use it?"

You don't have to be a pacifist—in fact, you can still support a perfectly potent defensive capability—to believe that scaling back the military apparatus to something less expensive, dangerous and tempting might be a wise idea. We could probably get by with 10 or 15 percent of the world's total military budget, and still be fully able to clobber anybody who picked a fight wiith us.

There are no guarantees. The elected and appointed political leaders of this country have proven themselves entirely competent to extract the worst possible outcomes from any circumstances. But without such an enormous hammer, the world's trouble spots might look to them a bit less like nails.

Show Comments (38)