Miami Beach Homeless Arrests Spiked in February Under Anticamping Law

During one week in February, arrests of homeless people accounted for 66 percent of all arrests in Miami Beach.

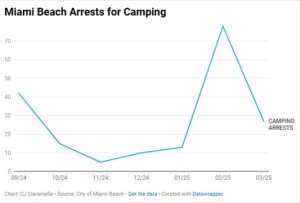

Arrests of homeless people in Miami Beach for violating new anticamping laws sharply spiked in February, according to public records obtained by Reason.

In one particular week in mid-February, arrests of homeless people made up two-thirds of all arrests in Miami Beach.

The numbers are a glimpse into enforcement of anticamping laws in the city that became a model for the rest of Florida. And Florida is now leading a national crackdown following a Supreme Court decision that it's not cruel or unusual punishment to criminalize sleeping in public, even when there was no other shelter available. When Florida Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a statewide law last year banning cities from allowing camping in public, he chose Miami Beach for the location.

DeSantis and Miami Beach officials say the laws are a firm but compassionate way to get people off the street and stop unsightly tent camps. However, homeless advocacy organizations and civil rights groups say criminalizing homelessness is cruel and counterproductive.

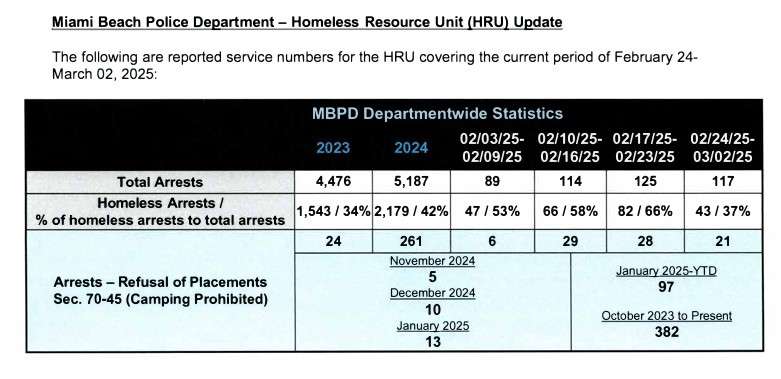

The arrest statistics were obtained from weekly memos that the Miami Beach city manager sent to the city council from last September through May on homeless outreach and enforcement. All of the memos are available here.

The memos show that in 2024, Miami Beach police arrested 261 people under an anticamping ordinance that it strengthened in October of the previous year.

The Miami Herald reported this January that, in addition to the anticamping ordinance, Miami Beach police were heavily enforcing quality-of-life offenses and nuisance crimes along the iconic beach and boardwalk. The result, the Herald reported, was that 42 percent of all Miami Beach arrests in 2024 were homeless people.

That kind of percentage isn't unheard of; in 2022 Oregon Public Broadcasting reported that roughly half of all arrests in Portland over a four-year period were of homeless people.

According to a March memo from the Miami Beach city manager, the number of arrests for prohibited camping went from 10 and 13 in December and January, respectively, to 78 in February. The number of camping arrests dropped to 27 in March.

During the week of February 17, Miami Beach hit a particularly eye-popping statistic: Of the 125 total arrests that week, 82—66 percent—were of homeless people.

Of the 445 total arrests by Miami Beach police in February, 238 were homeless—53 percent.

During that same period, the Miami Beach Police Department Homeless Resource Unit placed four people in emergency shelters or residential treatment, according to city memos. The city's other homeless outreach services recorded dozens of placements, but also hundreds of refusals of service.

A spokesperson for the city of Miami Beach said in a statement to Reason that "no directive was issued to focus on the camping ordinance, and our approach continues to balance enforcement with outreach and care."

"The City of Miami Beach remains deeply committed to treating all individuals, including those experiencing homelessness, with dignity and compassion," the statement continued. "While we continue to prioritize public safety and the appropriate use of public spaces, we recognize the complexity of homelessness and actively work with our Office of Housing & Community Services to connect individuals with shelter and supportive services."

Under Miami Beach's anticamping ordinance, police must give homeless people the option of being transported to an available shelter. If they refuse, they can be arrested and taken to jail.

However, a Miami Herald review of arrests made after the city's public sleeping ban was enacted found Miami Beach police officers asked "only vague questions about whether homeless people want shelter or other assistance before detaining them. Officers do not appear to discuss the availability of beds in specific shelters, offer transportation to the shelters or explain that declining services will result in their immediate arrest."

Things used to be different. From 1992 to 2019, Miami was prohibited under the terms of an American Civil Liberties Union lawsuit settlement from arresting homeless people for sleeping, bathing, or other essential activities.

David Peery was homeless in Miami from 2008 to 2018 and was the class representative for homeless plaintiffs in the consent decree that resulted from the settlement.

Peery, now the founder and executive director of the Miami Coalition to Advance Racial Equity, was shocked by the February statistics. He says they show a "remarkable and deeply troubling diversion of police resources."

"They're spending their time chasing people whose only crime is not being able to afford a home," Peery says. "It's totally fiscally irresponsible and cruel."

As Reason's Christian Britschgi wrote, if cities are going to outlaw sleeping in public, they should also be working to deregulate and expand the types of housing they allow, but in many cases local governments are instead fighting new housing and trying to shut down shelters.

The spike in arrests also doesn't make sense to Peery because homelessness is going down in Miami-Dade County. In January, before the spike in arrests, the Miami-Dade County Homeless Trust reported a 31 percent drop in unsheltered homelessness in Miami Beach over the previous year.

There was one major event on the calendar that month. The Miami International Boat Show took place February 12–16. Boatingindustry.com wrote that the trade show expected 100,000 attendees from around the world and was projected to generate $1 billion in economic activity for the state of Florida. DeSantis was on hand to offer a speech on freedom for recreational boaters.

It's not uncommon for cities to roust homeless people to make way for high-profile events and VIPs. Last March, for example, the Miami Herald reported that police ordered homeless people to move out of an area where filmmakers were shooting Bad Boys: Ride or Die.

"It's more important to hide homelessness than to solve it," Peery sighed.

Show Comments (68)