Frederic Jameson: Beloved Authoritarian

His famous erudition was attached to his nightmare politics.

The American academia from which I recently retired is not an overwhelmingly authoritarian institution. Sure, the administration may police speech here and there. And certainly the system sorts people very early by ideology; during my career, those who disliked the consensus political positions, or who couldn't conceal their disagreement for years on end, didn't tend to make it out of grad school. But the purges are relatively gentle, and the institutions do not, by and large, feature internment facilities or beatings or executions.

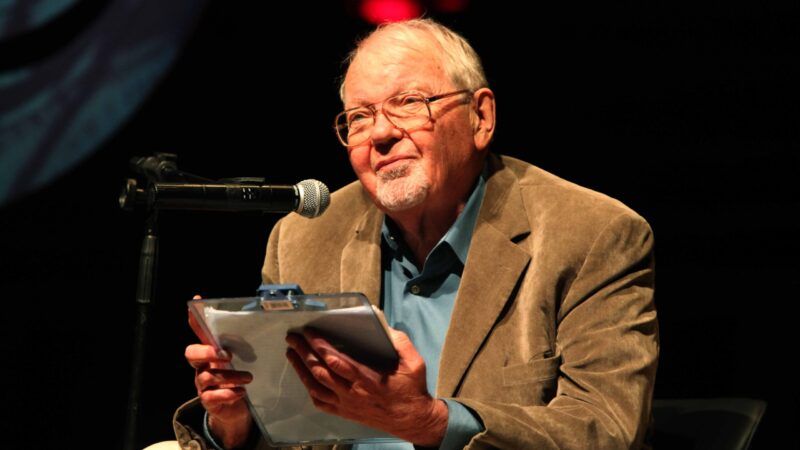

Nevertheless, many professors I worked with deeply admire authoritarianism. Nothing better illustrates this point than the reception of the late literary theorist Frederic Jameson, who Jacobin dubbed "the leading Marxist literary and cultural critic in the United States, if not the world," and The Nation called "an intellectual titan and one of the torchbearers of Marxist thought through the tenebrous night of neoliberalism." For the mighty critic Terry Eagleton, "Jameson was the finest theorist of all."

Jameson was remarkably influential. He didn't coin the terms "postmodernism" or "late capitalism," but his big 1991 book Postmodernism: Or, the Logic of Late Capitalism seemed to inform everyone what they meant. The book wandered through visual arts, literature, architecture, politics, and media, trying to make sense of the 1980s. More to the point, it applied Marxist theory in a way that the emerging academic left turned out to be yearning for.

A pretty good emblem is that phrase, "late capitalism." It appeared to be an attempt to give a historical account of the then-present, but it also has the quality of a wish. If it's late, it's almost over. Jameson, and seemingly everyone I knew, were expressing their desire every time they uttered their name for their time. A famous sentence is often attributed to Jameson, though he did not take credit for it: "It's easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism." Well, even just the incessant use of 'late,' along with the demonstration that Marxism could be still be mentioned in the English department in 1992, filled many professors with hope.

All the tributes listed above, and many more besides, express reservations about Jameson's writing, with its swaggeringly didactic, voice-of-god tone, its quick tendentious takes on a dozen texts per page, and its ought-to-be infamous tics (such as randomly dropping the phrase "as such" every few sentences to lend weight to abstract concepts). But even as the obituaries admitted here and there that there were some drawbacks to Jameson's work, none appeared to take issue with his dogmatic Marxism. And Jameson was definitely a dogmatist. In his 1981 book The Political Unconscious, he called Marxism the "untranscendable horizon" that "subsumes" other "apparently antagonistic or incommensurable" approaches to literary criticism, "thus at once canceling and preserving them."

And the Marx at the center of Jameson's writings is the worst possible version of the thinker. Jameson interprets Marx the same way Marx's most vociferous enemies interpret him: as a totalitarian.

Many things that had always been true of Jameson became obvious late in his life, with 2016's An American Utopia: Dual Power and the Universal Army. One explicitly invoked source of Jameson's ideas in this book is Leon Trotsky's 1920 text Terrorism and Communism, in which Trotsky treated terrorism as an indispensable revolutionary and governing strategy. (In the French Revolution, Trotsky casually suggested, a lot more Terror would have been a lot better.) Trotsky's book also argued for the total militarization of society, starting with labor, which he said should be organized into "industrial armies." And not freely formed ones: "Organized economic life," he wrote, "is impossible without compulsory labour service….The very principle of compulsory labour service is for the Communist quite unquestionable. 'He who works not, neither shall he eat.'" That's not exactly "From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs."

This, of course, was written just after a dramatic revolution, with counterrevolutionary armies still in the field, as the Bolsheviks were trying to consolidate power in a situation of chaos. But Jameson regards the program as desirable right here and now.

An American Utopia argues that the left has lost its political imagination and that we need a return to a utopian vision, a sense that a better world is possible. Intending to inspire us, Jameson recommended the most grindingly oppressive totalizing regime that could be, a nightmare vision indistinguishable from a post-apocalyptic dystopia.

Let's look at some of the half-developed details. "The first step in my utopian proposal," Jameson wrote, is "the renationalization of the army along the lines of any number of other socialist candidates for nationalization…by reintroducing the draft to transform the present armed forces back into that popular mass force. First of all, the body of eligible draftees would be increased by including everyone from sixteen to fifty, or, if you prefer, sixty years of age, that is, virtually the entire adult population." At some point, this "universal army" will shuck off the old "representative" government, in something that seems like a military coup, and be the sole authority, allegedly identical with all the people.

The military, Jameson says, will provide health care to all. "Pharmaceutical production, disease control, and experimentation with and production of new medicines, would now be reorganized and situated within the army itself." That is, the army will also be the sole public health authority. It will also be the sole provider of education, and the sole employer, manufacturing clothing and automobiles, infrastructure and shelter. Jameson urges "immediately placing this institution (if it can still be called that) in charge of the ordering and supply of food production and therefore in a controlling position for that fundamental dietetic and agronomic activity as well."

This is totalitarianism indeed: a nation that has mobilized its entire population for total war and dedicated itself to controlling every practical aspect of their lives. This cannot make even for a plausible fiction, though this part resembles a lot of current dystopian writing:

We may provisionally call this new institution the Psychoanalytic Placement Bureau, and it will, in conjunction with unimaginably complex computer systems, handle and organize all forms of employment as well as all manner of personal and collective therapies….The new institution will combine the functions of a union and a hospital, an employment office and a court, a market research agency, a polling bureau, and a social welfare center. Presumably, what is left of the police as an institution will eventually be absorbed in this collective agency, which will eventually replace government and political structures equally, the state thereby withering away into some enormous group therapy.

A highly militarized group therapy, we might add. Jameson also suggests, in an almost flippant aside, that the populations of New York and Shanghai should be forced to switch places.

Jameson had a ready reply to anyone who accused him of totalitarian designs: that people who talk about totalitarianism (and for that matter freedom or individuality) are bourgeois reactionaries expressing their hatred of "the collective as such." Toward the end of An American Utopia, Jameson reaches a "sobering assessment": "the human species is a particularly loathsome biological entity, and this [is] very much owing to its individuality (and freedom) rather than the lack of it."

If Frederic Jameson were still alive and having his way, individuality and freedom would be impossible. If the chained shade of Jameson comes for us, be ready to dodge the draft.

Show Comments (20)