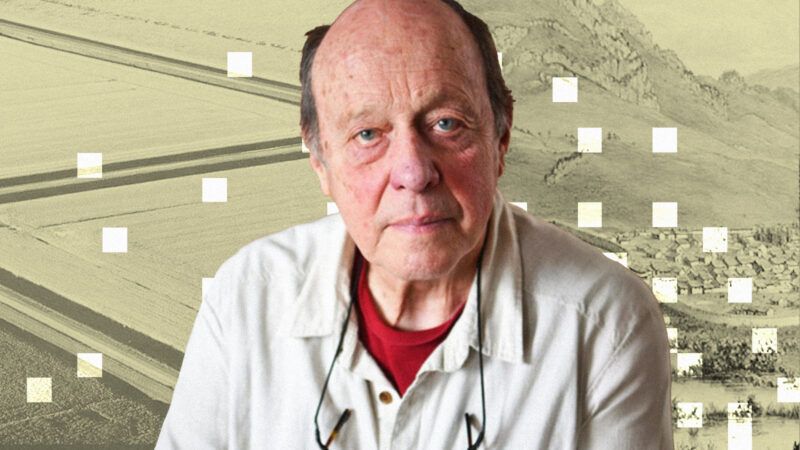

What James C. Scott Taught Us About Liberty, Authority, Surveillance, and Resistance

Scott wrote about the ways people resist authority—and the unmapped territories where much of that resistance takes place.

James C. Scott, who died July 19 at age 87, was one of the most original and radical political theorists of the past century.

Beginning as a political scientist studying Southeast Asia and then expanding to other disciplines and to the rest of the globe, Scott wrote about the ways authority exerts itself, about the ways ordinary people resist or avoid that authority, and about the unmapped territories where that resistance often takes place. I mean unmapped both figuratively (as when he recounted how Malaysian farmers covertly evaded the Islamic government's tithes) and literally (as when he described the uncharted marshes and mountains where people could escape state power). Scott's wide-ranging studies took in everything from Br'er Rabbit tales in the Old South to urban planning in Brazil, from Stalin's war on the Russian peasantry to Maya Lin's Vietnam Veterans Memorial, from the origins of grain farming to the origins of the Tennessee Valley Authority.

The storyline that emerges from those explorations isn't a conventional account of grand states and empires. It isn't a romantic longing for a lost golden age before those states and empires either. It's a dynamic vision where the zones of centralized authority and the zones of relative liberty are constantly adjusting to one another, so that one might, say, flee the conscription and taxes being imposed by state centers but still lurk around the frontiers, trading with your former overlords. While the borders on a map stay static, a state's actual reach might grow and shrink with the seasons. At times it might disappear altogether. And even where hierarchical power seems to be strongest, there will be tiny spaces for free action, or at least for little acts of sabotage and ridicule. To quote an Ethiopian proverb that Scott put at the beginning of his 1990 book Domination and the Arts of Resistance: "When the great lord passes the wise peasant bows deeply and silently farts."

This vision took a while to reveal itself. At the beginning of his career, Scott didn't seem radical at all: Fresh from college in the 1950s, he went to work for the CIA, filing reports on Burmese student politics. (A decade later, in a sign of how much Scott's worldview had evolved, he refused to take a job at MIT because it would have entailed doing research for the Pentagon.) In the 1970s and '80s, he became known for his writing on the subsistence economy of Asian peasants—and, after two years of fieldwork in a Malay village, of the ways peasants find to route around laws and other impositions they dislike. This expanded into an interest in the ways all sorts of people, peasant or not, route around impositions they dislike, particularly in societies where they cannot change policies through democratic means.

And that led to an interest in how the authorities, in turn, move to block such routes. In particular, Scott became fascinated with how governments try to track and map all that activity happening beyond their ken—and how authoritarians try not just to map their societies but to remold those societies to make them more mappable. That became a central theme of Scott's most famous book, 1998's Seeing Like a State.

Scott is sometimes described as an anarchist, and he was influenced by a number of anarchist thinkers (especially Colin Ward). But he was ambivalent about whether abolishing the state entirely was a practical goal—to quote one of his book titles, he gave just Two Cheers for Anarchism. Nor would he describe himself as a free-market libertarian: While there was obvious overlap between his thinking and, say, Friedrich Hayek's ideas about dispersed knowledge, Scott saw his work as a critique of large-scale corporate capitalism as well as of the state. In an oral history interview conducted in 2018, he remembered William Niskanen of the Cato Institute calling to ask if he would speak at a libertarian event: "I remember my partner was with me and I put my hand over the phone and said to her, 'What have I done wrong that the Cato Institute is calling me and wants me to sort of talk at their conference?'" (I should add, though, that he was friendly the couple of times I approached him about reviewing books for Reason. Indeed, he agreed to write about the second book I pitched to him, though he later decided that the text wasn't good enough to be worth reviewing. Of course, for all I know he was looking up from my emails and asking whoever happened to be passing by, "What have I done wrong that Reason magazine wants me to write for them?")

In any event, many of us who do accept the libertarian label got a lot out of Scott's work. He is probably one of the four or five strongest individual influences on my own thinking, and I cite him frequently—not just when directly discussing his books, but when writing about topics ranging from political charisma to the history of Haiti. And even when I'm not actually citing him, there's a good chance he's shaping my thinking. When I wrote last year about the all-black towns that emerged after Reconstruction, I never mentioned Scott by name, but his intellectual fingerprints were all over the article.

So I say this enthusiastically: You should read Scott. His books and papers represent a wider, deeper way of thinking about politics—one that extends far beyond the formal institutions that try to govern our lives but only sometimes succeed.

Show Comments (5)