Biden and Journalists Agree: Republicans Would Deliberately 'Crash' the Economy

But…does that make any sense?

As Democrats and the journalists who root for them navigate the fraught final two weeks of an increasingly grim-looking midterm election campaign, many have settled on a message to counteract criticism over the anxiety-inducing state of the national economy: Republicans are worse because they would wreck it on purpose.

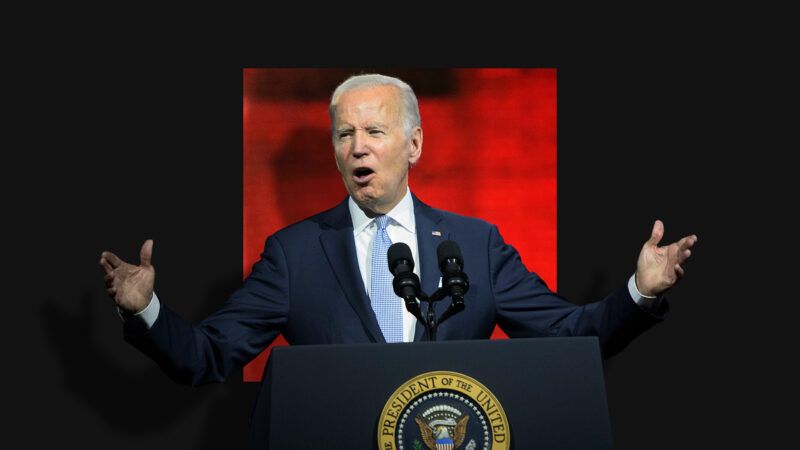

"If you're worried about the economy, you need to know this Republican leadership in Congress has made it clear they will crash the economy next year by threatening the full faith and credit of the United States," President Joe Biden alleged on Friday. "For the first time in our history, putting the United States in default unless we yield to their demand to cut Social Security, Medicare."

It's "not just democracy…at stake this fall," warned the subhed on a recent Atlantic piece by D.C. establishment lifer Norm Ornstein. No: "If Republicans win control of the House of Representatives, the country will face a series of fundamental challenges much greater than we have had in any modern period of divided government, including a direct and palpable threat of default and government shutdown….The concessions demanded by the new MAGA extremist radicals will be non-negotiable. And this time, if Republicans win, a lot more members will be ready to push us over the cliff."

It may seem hyperbolic to assert that a GOP-run 2023–24 Congress will bring fundamental challenges "much greater" than the 1974–76 divided-government era of Watergate, inflation, the Church Committee, and the fall of Saigon, but it is possible, even probable, that I lack a certain catastrophic imagination.

I do, however, have at least some standing to judge the accuracy of this recent headline from New York Magazine political columnist Jonathan Chait: "Republicans Plan Debt Crisis to Force Cuts to Medicare, Social Security: They do this every time."

Reader, they do not do this every time.

On November 4, 2014, Republicans won back control of the United States Senate for the first time since 2007, ushering in the only fully oppositional Congress of Barack Obama's presidency. On November 5, incoming Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R–Ky.), said, "Let me make it clear: There will be no government shutdowns and no default on the national debt."

Congress made good on McConnell's promise the following fall, suspending the debt ceiling until after Obama left office. Since then, the only influential House member to make even mild negotiating noises about the borrowing cap has been Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D–Calif.).

The GOP's fiscal progression from backbenching ballbusters in 2010–2013 to lower-drama accommodationists from 2014–2016 to big-government enablers from 2017–2020 is a fascinating and consequential subject; here's a 2018 stab I made at a devolutionary timeline. In order to arrive at the conclusion that, as Matthew Yglesias wrote recently in the Washington Post, "a Republican win is pretty much a guarantee of a political and economic crisis whose goal is to enact fiscal austerity," you need to leapfrog over all that recent history, and disregard the fact that the party's most popular politician campaigned explicitly on protecting entitlements and then presided over a larger spending increase in his first three-and-a-half years—pre-pandemic, mind you—than Obama managed in eight.

So what, besides political PTSD, is prompting this confidence in such an apocalyptic assertion? (Chait again: "It is…highly likely that they will attempt to melt down the global economy as part of an extortion threat.") One consideration is the general increase in Republican loopiness and obstinance in the age of Trump, regardless of their hero's open hostility to Paul Ryan-style entitlement reform. (Remember, the two government shutdowns under Trump came not because Republican lawmakers wanted to spend less, but because a Republican president wanted to spend more, on border enforcement.)

In Ornstein's formulation, the Crazy Party has just gotten more crazy: "Tea Party radicals—who a few years later formed the Freedom Caucus because the existing right-wing caucus, the Republican Study Committee, was not right-wing enough—have moved from the fringe to the center among House Republicans. And if Republicans capture a majority in next month's midterm election, they will make the Tea Party group look like milquetoast moderates."

More specifically, four House Republicans told Bloomberg News earlier this month that they would like to use the debt ceiling as leverage to cut spending growth. "Our main focus has got to be on nondiscretionary—it's got to be on entitlements," Buddy Carter (R–Ga.) told the service. Lloyd Smucker (R–Pa.) suggested means-testing; Jodey Arrington (R–Texas) talked about raising the retirement age.

And, in one of those straight-to-the-filing-cabinet, we'll-balance-the-budget-in-seven-years-no-really white papers, the Republican Study Committee this summer put out a blueprint that would gradually increase the age of Social Security recipients, tweak disability payments, and encourage the creation of younger-worker opt-outs that will almost certainly never be acted upon during my lifetime. There is ample ooga-booga potential here for Democratic cherry-pickers. Also, the relevant entitlements-related chapter headings are "Saving Medicare," "Reforming Disability Insurance," and "Make Social Security Solvent Again."

Then last week, House minority leader (and presumed speaker-in-waiting) Kevin McCarthy (R–Calif.) was asked by Punchbowl News about the debt ceiling. This was his answer:

You can't just continue down the path to keep spending and adding to the debt. And if people want to make a debt ceiling [for a longer period of time], just like anything else, there comes a point in time where, okay, we'll provide you more money, but you got to change your current behavior. We're not just going to keep lifting your credit card limit, right? And we should seriously sit together and [figure out] where can we eliminate some waste? Where can we make the economy grow stronger?

Eagle-eyed observers will detect the utter lack of anything concrete or even urgent here, further buttressed by McCarthy's response to a follow-up question about entitlement reform that he wouldn't "predetermine" anything about any future discussions.

Cue the death gongs.

"Minority Leader McCarthy indicated his support for House Republicans' increasingly open plotting to threaten a catastrophic economic meltdown in order to force wildly unpopular cuts to the bedrock of American seniors' financial security," bellowed Pelosi's press shop. "Leader McCarthy is just the latest of a growing list of extreme MAGA Republicans who have not-so-subtly suggested brutal cuts on Medicare and Social Security."

Well sure, that's a politician's reaction, but what about a responsible journalist? "Republican leaders—by their own admission—are prepared to provoke a global financial crisis, on purpose," wrote MSNBC's Steve Benen. Oh.

In the event, it took Kevin McCarthy all of one day to furiously walk back even the perception about his remarks.

"I never mentioned Social Security or Medicare," the Bakersfieldian said on CNBC. "Actually, in the 'Commitment to America,' we say to strengthen Social Security and Medicare….The debt ceiling needs to be raised, but I also know I'm going to strengthen Social Security, Medicare."

McCarthy does not have a reputation for being the sharpest tool in the shed. In contrast, his senior counterpart Mitch McConnell—you know, the guy who so eagerly ditched the debt ceiling as a negotiating tool in December 2021 that Donald Trump called him a "Broken Old Crow"—is known by friend and foe alike for being among the canniest legislative operators in American politics. McConnell has shown zero enthusiasm for debt-ceiling brinksmanship and government shutdowns for going on nearly a decade now; McCarthy popped a tepid trial balloon after just 24 hours.

No matter. The emerging media/Democratic consensus, even in the absence of anything like an actionable plan or visible campaign politics around using the debt ceiling to force entitlement cuts, has solidified around accusations of deliberate economic sabotage.

"There's nothing—nothing—that will create more chaos, more inflation, more damage to the American economy than this," Biden said Monday. "Republicans are determined to hold the economy hostage….It's outrageous."

Echoed MSNBC host Chris Hayes Tuesday night: "This is blindingly obvious, but worth stating over and over. A GOP house majority would have every incentive to do whatever possible to make the US economy worse in the run-up to 2024. The only reason *not* to do that is some sense of public duty, and I'm not holding my breath."

It is worth noting even in a speculative piece of writing about entitlement-related politics that the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund is headed toward depletion by 2026, and that Social Security is currently projected to reach insolvency in 2034, after which (if nothing is changed) come mandatory, across-the-board 20 percent cuts to every recipient. This used to be the type of predictable, well-documented, long-range catastrophe that politicians from both major political parties felt motivated to warn about and even organize around now and then—the subject came up in every State of the Union Address from 1997 to 2013, for example.

In fact, one of the key reasons that entitlement-reform negotiations were on the table from 2010–2013—and likely will not be in 2023–24—is that a Democratic president helped put them there. "There's no doubt that we're going to have to…address the long-term quandary of a government that routinely and extravagantly spends more than it takes in," Barack Obama said in February 2010, while announcing the new National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, co-chaired by Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles. "Without action, the accumulated weight…of ever-increasing debt will hobble our economy, it will cloud our future, and it will saddle every child in America with an intolerable burden."

The Simpson-Bowles framework, which involved (among many other things) raising the age of Social Security and subjecting some entitlements to means-testing, failed to receive enough votes in the bipartisan committee, though it did lead directly to the Budget Control Act of 2011, the creation of yet another eventually-failed bipartisan entitlement reform committee, and—as a triggered punishment of that committee's failure—sequestration spending caps.

The Tea Party-wave midterm elections of 2010, in which whole swaths of often-insurgent Republicans campaigned directly and loudly on spending cuts and entitlement reform, obviously influenced the contentious fiscal politics of those years. But there were also some willing Democrats on the other side of the table.

How does that compare to 2022? Limited-government conservatism has gone the way of the dodo bird—if there are any Rand Pauls or Thomas Massies in the freshman 2022 class, I certainly haven't heard of them. The rising National Conservatism movement is explicitly big government; the hot policy action in the GOP is about expanding welfare to encourage families.

Democrats have changed, too. Twelve years after his boss entertained demographic tweaks to old-age entitlements, Biden has taken to labeling any such proposal as "ultra-MAGA." Key to that absurd mislabeling is the dramatic elevation of a February "Rescue America" pamphlet from Sen. Rick Scott (R–Fla.) whose entire explicit verbiage about entitlements is contained within one sentence: "Force Congress to issue a report every year telling the public what they plan to do when Social Security and Medicare go bankrupt."

How, exactly, does this amount to cutting Medicare and Social Security, as Biden charges daily from the stump? Via this passage from Scott: "All federal legislation sunsets in 5 years. If a law is worth keeping, Congress can pass it again." In the president's hands, these 18 aspirational words, untethered to any imagined mechanism or draft bill, became this:

He's proposed a plan to put Social Security and Medicare on the chopping block every five years. If you don't vote for it again, it goes away. That means every five years, Congress will vote to cut, reduce, or completely eliminate Social Security and Medicare.

Turns out that Scott was asked directly back in March whether he wants to "potentially sunset programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security." His response:

No one that I know of wants to sunset Medicare or Social Security, but what we're doing is we don't even talk about it. Medicare goes bankrupt in four years. Social Security goes bankrupt in 12 years….I think we ought to figure out how we preserve those programs. Every program that we care about, we ought to stop and take the time to preserve those programs.

Rick Scott, influential though he is, does not run the Republican caucus in the Senate. The man who does, Mitch McConnell, had this initial reaction to Scott's blueprint: "We will not have as part of our agenda a bill that raises taxes on half the American people and sunsets Social Security and Medicare within five years."

In their cascade of confident doomsaying about GOP entitlement-slashing and economic sabotage, left-of-center commentators have hit on one almost uncannily similar theme. "The one political fight that's likely to matter most next year is the one thing most voters are hearing very little about," Steve Benen wrote. "The single biggest thing at stake in next month's midterm elections has attracted only a sliver of…attention," agreed Matthew Yglesias. "The most important question," Paul Krugman averred, "will be one that is getting hardly any public attention: What will the Biden administration do when the G.O.P. threatens to blow up the world economy by refusing to raise the debt limit?"

Maybe voters are blind to what only anti-GOP columnists can see. Maybe serious entitlement-reform groundwork has been laid by Republicans without attracting any notice from the libertarians who are actually interested in the issue.

Or maybe the explanation is simpler than that.

Bonus Remy content:

Show Comments (182)