NIH Awarded More Than 56,000 Grants in 2020. Just 2 Percent Were for Studying COVID.

More evidence that the public health bureaucracy dropped the ball when a once-in-a-generation pandemic hit.

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government approved an unprecedented amount of emergency spending in response to a new and poorly understood public health threat.

But the federal government's agency dedicated to actually studying public health threats was slow to respond.

In fact, just 2 percent of the more than 56,000 grants issued by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) during 2020 went to projects studying COVID-19, even as the virus killed thousands of Americans and ransacked the global economy. That's the conclusion of a new study from researchers at Johns Hopkins University and Penn State University that's been accepted (but not yet peer-reviewed or published) by The BMJ, a Britain-based medical journal.

"In the first year of the pandemic, the NIH diverted a small fraction of its budget to COVID-19 research," the researchers conclude. "Future health emergencies will require research funding to pivot in a timely fashion and funding levels to be proportional to the anticipated burden of disease in the population."

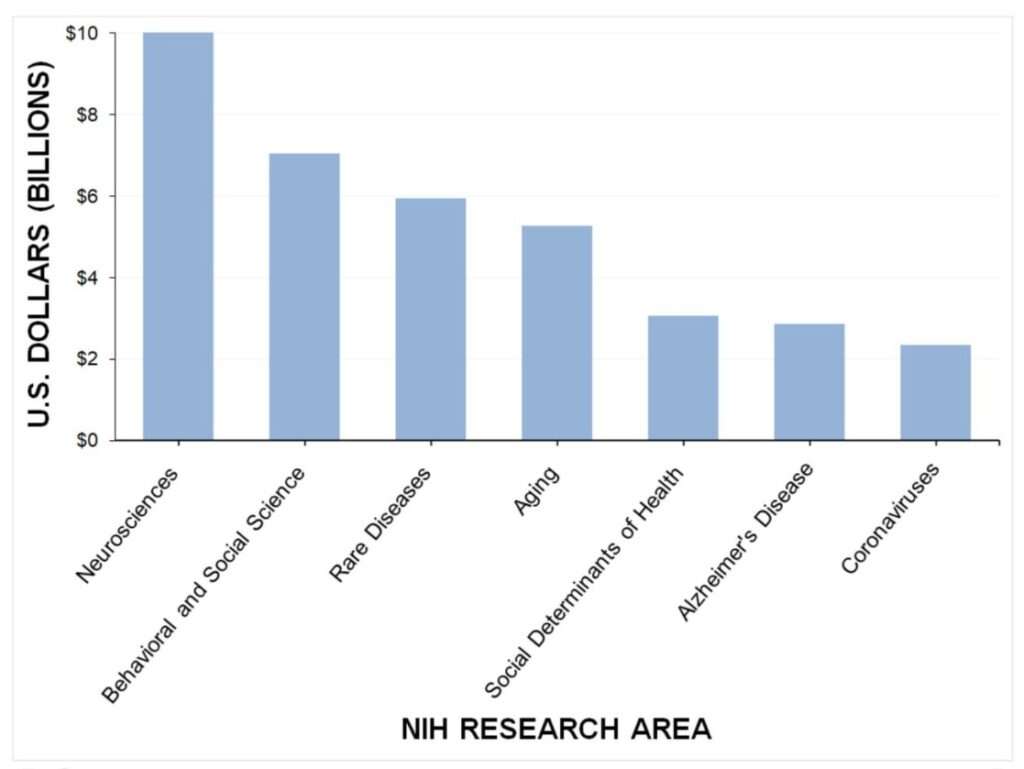

The 1,108 grants awarded for studying COVID-19 accounted for just 5.3 percent of the NIH's $42 billion budget in 2020, according to the report. The NIH dedicated significantly more funding toward behavioral and social science research than coronaviruses during 2020. Studies of rare diseases received about 2.5 times as much funding as coronavirus research, while research into aging got more than twice as much funding.

The COVID-19 research that was funded took a while to get approval. Researchers found that the average time it took for the NIH to approve a COVID-related project was 151 days, with most funding not delivered until the final months of the year.

"The lack of rapid clinical research funding to understand COVID-19 transmission may have contributed to the politicization of the virus," the researchers argue in the paper. "Some of the most basic questions that were being asked of medical professionals in early 2020, such as how it spreads, when infected individuals are most contagious, and whether masks protect individuals from spreading or getting the virus, went unanswered. In the absence of evidence-based answers to the common questions the public was asking, political opinions filled that vacuum."

The study should raise more serious questions about the public health bureaucracy's ability to respond quickly to a developing crisis. For years, the NIH was frequently criticized by figures like Sen. Rand Paul (R–Ky.) for funding wasteful studies that fed cocaine to Japanese quail and nicotine to zebrafish. But when former President Donald Trump proposed cutting the NIH budget by $4.5 billion in 2019, the agency's defenders fretted that the public would miss out on future "ideas and breakthroughs" that would have been generated with those grants.

The COVID-19 pandemic offered a real-world opportunity for the NIH to prove its value. Like the other aspects of America's public health bureaucracy—the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration—the NIH seems to have failed that test.

By comparison, a private-sector effort that started from scratch at the beginning of the pandemic was able to invest $50 million in COVID-19 research during 2020. The so-called Fast Grants program was a joint effort of Tyler Cowen, an economics researcher at George Mason University; Patrick Collison, co-founder of Stripe, an online payment platform; and Patrick Hsu, a scientist at the University of California, Berkeley. Nature reported in August 2021 that 67 percent of grant recipients "said their research wouldn't have been possible without a fast grant, and about one-third said it accelerated their work by months."

Fast Grant applications were designed to be completed in less than an hour, with funding decisions made in two days and money delivered within a week.

That stands in stark contrast to the timeline for NIH grants. "From the beginning, the institutional response [to COVID-19] has been lethargic," wrote Cowen, Collison, and Hsu in a June 2021 blog post reviewing their project. "We found that scientists—among them the world's leading virologists and coronavirus researchers—were stuck on hold, waiting for decisions about whether they could repurpose their existing funding for this exponentially growing catastrophe."

Specifically, they pointed to the fact that NIH grant applications require three phases of review by as many as 20 different scientists. No one is harmed by a long review process for a project that gives blow to birds, but the COVID-19 pandemic required a speedier response that wasn't possible for creaky government bureaucracies. "It is difficult for these bodies, such as the NIH, to adapt as circumstances change," the trio concluded.

The new research from Johns Hopkins and Penn State seems to confirm what Cowen, Collison, and Hsu were seeing on the ground as the pandemic hit. The public health bureaucracy's failure to rapidly respond to a once-in-a-generation crisis likely slowed crucial research, left scientists in the dark about how the coronavirus spreads, and created space for misinformation to reign.

We could have followed the science—if only the bureaucrats weren't getting in the way.

Show Comments (57)