All Politicians Are Unpopular—So Strip Away Their Power

Shrink the federal waistline for healthier communities.

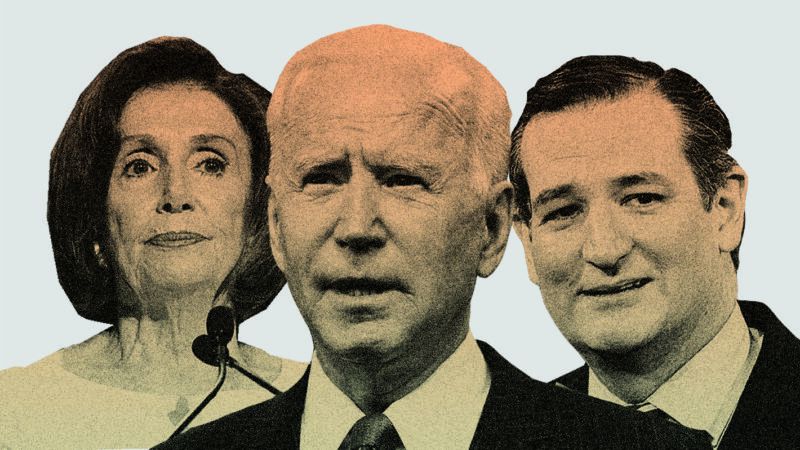

As we begin what will surely be another tumultuous year in politics, I'd like to congratulate our leaders in Washington for uniting our fractious country around a common proposition: We don't like you.

President Joe Biden is unpopular. Former President Donald Trump is unpopular. Congressional leaders are unpopular. More generally, a recent Gallup survey shows that only 39 percent of Americans have either "a great deal" or "a fair amount" of trust and confidence in the federal government to handle the nation's problems. Regarding Congress in particular, most Americans describe their level of confidence as "very little" or "none."

A healthy skepticism about the pretensions of politicians and the exercise of federal power is nothing new in American life. What we face now, though, is quite unhealthy cynicism. It's toxic. And while we have lately endured a series of especially inept and unctuous leaders, the problem is really one of institutions, not individuals.

Regardless of party, we've allowed the political class to strip too much authority from states, localities, and communities. That power (and, not coincidentally, the attention that comes with it) has been drawn to the nation's capital. Changes in media consumption have enabled and accelerated the trend. Political careers are made with cable news clips and viral tweets aimed at true believers, not by building real coalitions, serving constituents, or enacting durable policy reforms.

In short, Washington has gotten too big for its britches. Can it lead us to a better future? Of course not. It can barely waddle. And swapping out blue pants for red pants, or vice versa, won't make much difference.

Tony Woodlief, executive vice president of State Policy Network (of which I am a board member), offers a different solution: Shrink the federal waistline. In his fascinating new book I, Citizen: A Blueprint for Reclaiming American Self-Governance, Woodlief argues that the nation's capital has become "an imperial city." Its conquests have not only overturned America's constitutional order but also needlessly made enemies of citizens who, despite their many disagreements, ought to be able to live together in peace and mutual respect.

"A decades-long ideological war waged by political elites in our name," Woodlief writes, "has punctured the reservoir of goodwill that characterized American civic life for generations. Simultaneously, centralization of power in D.C. has eroded the authority of our elected legislatures, which has reduced control over our own government."

If you think Woodlief is only blaming elected officials for this state of affairs, you're mistaken. The political class he describes includes journalists who for their own purposes devote more attention to clowns than to conciliators. It includes pollsters who construct either-or questions to produce artificially rigid measures of polarization. It includes consultants and activists and other private interests who prefer to play their rigged game in the Washington casino rather than having to engage us in the real, robust, inherently untidy communities across our sprawling country where we spend most of our time pursuing our own conceptions of the American dream.

Moreover, if you think Woodlief's book concludes with one of those standard, wonky checklists of public policies that can "solve" the problem, you're mistaken again. While he supports some institutional reforms of the federal government, such as strengthening the Government Accountability Office, Woodlief thinks it's more important to strengthen our state governments, local governments, civic associations, and families so they can more effectively resist federal encroachment and offer Americans more opportunities to exercise true citizenship closer to home.

It's a hopeful message for what is still, at its core, a hopeful nation. "We are not broken," Woodlief concludes, "the political class is. We are not at war, they are."

Show Comments (151)