Indians and Aliens

Human beings' disturbing capacity to manufacture history to serve our own ends

The Mound Builder Myth: Fake History and the Hunt for a "Lost White Race," by Jason Colavito, University of Oklahoma Press, 386 pages, $24.95

It took Jason Colavito eight years to write The Mound Builder Myth, but the project seems tailor-made for 2020. It starts with multiple waves of a pandemic and ends with conspiracies, white supremacists, and a battle between science and superstition.

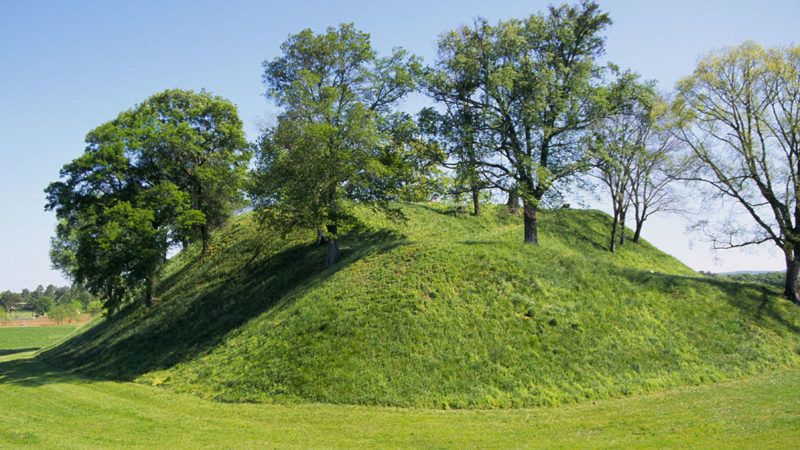

At the heart of the book lie the large earthen mounds that cover a vast portion of North America. The earliest of these, Colavito points out, "were standing in their solemn glory five centuries before the Egyptians raised their pyramids." They were built by Native Americans, but in the 19th century a legend took hold that a lost white race had constructed them. This manufactured myth didn't just ignore indigenous American civilizations. It fed into the theft and ethnic cleansing of the indigenous people's lands.

In this century-spanning work of U.S. intellectual history, Colavito describes how a determined few replaced the truth of who built the ancient earthen mounds in North America with a long-lasting "monumental deception" backed by many political leaders, including several U.S. presidents. The lie has now been exposed, but Colavito argues that the "constellation of ideas" that supported it persists today.

From approximately 4500 B.C. through the time of European colonization, diverse American peoples produced different kinds of mounds. The Poverty Point culture produced concentric semicircles of mounds in the lower Mississippi Valley and surrounding Gulf Coast over the course of nearly 1,000 years. The Adena and Hopewell cultures produced more than 10,000 mounds in geometric and animal forms in the Ohio Valley. The Cahokia civilization of the Mississippi Valley spread mounds from present-day Louisiana to New York, created an urban center rivaling medieval London and Paris, and built Monks Mound, with a base the size of the Great Pyramid of Egypt and height of 100 feet.

European contact proved cataclysmic for much of indigenous America. The devastating spread of infectious diseases and violence left some native nations all but wiped out and others displaced or struggling. But even with this cultural rupture between pre- and post-contact societies, Europeans did not question the fact that indigenous peoples built the mounds. As late as the 17th century, Portuguese and French explorers observed Native Americans building new mounds in the style of the old.

The mounds became a source of fascination for Thomas Jefferson. His family home of Shadwell was built on property containing a mound he dubbed "Indian Grave"—one of 13 in the region. As a child, Jefferson witnessed local Monocans making pilgrimages to the site. As an adult who wished to study it systematically, Colavito explains, Jefferson would essentially "invent a new science, anticipating by more than a century the methodology of archeology." Jefferson's excavation led him to understand better how Monocans built mounds in stages over many years, layering graves upon graves. His observations became part of the only book-length work Jefferson published in his lifetime, Notes on the State of Virginia, which appeared in several versions in the 1780s. Jefferson sought to enhance popular understanding and appreciation of the mounds through scientific inquiry, but his work restated a consensus perspective of Europeans long before him: indigenous Americans built the mounds of North America.

Despite Jefferson, despite science, despite indigenous memory and action, despite firsthand observations of European explorers, the popular narrative about the mounds soon shifted. After making the case for the earlier consensus, Colavito investigates why "educated men at the highest levels of American and European science, government, and society" chose to argue that "that the mounds of the United States were not Native American constructions at all but rather the work of ancient—and white—Europeans."

One of the books that kicked off the movement was Travels in Upper Pennsylvania and the State of New York (1801). Its French-American author, J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, put his own words (and those plagiarized from several other people) in the mouth of an almost certainly fictionalized Benjamin Franklin, styled as the author's traveling companion. As Crèvecoeur's version of Franklin waxes poetic on their surroundings, he manufactures a new history for the new nation, replacing fact with a myth of an ancient and lost white civilization that thrived in North America and left the mounds as proof. This story made the displacement of the natives a kind of full-circle homecoming for white Europeans—a just reclaiming of the continent from barbarians.

"Europe and Asia had their ancient peoples, and the United States needed people every bit their equals," Colavito writes. "'Franklin' lamented to Crèvecoeur that the New World seemed mired in 'ignorance and barbarism,' while ancient Europe had flourished with civilization for 'thousands of ages.' The 'lost race' theory solved the problem at a single stroke. It excused the existence of 'savages' as interlopers and created a history for America as old as Europe's, with people as puissant and warlike as the Romans and as architecturally ambitious as the Egyptians."

The myth grew. The soldier, physician, and banker James H. McCulloh, for example, wrote Researches on America: Being an Attempt to Settle Some Points Relative to the Aborigines of America, &c., with one version published before the War of 1812 and others afterward. In this fanciful book, Colavito writes, McCulloh took those "scattered claims of an albino or white race" and built "an entirely new prehistory for America, stretching from the foundations of most ancient India through a great race war, whereby these ancient white people were destroyed and their superior culture hijacked by swarthy people." Colavito draws a line from the race-war rhetoric of this popular narrative to the anti-indigenous violence of such U.S. leaders as William Henry Harrison and Andrew Jackson.

With a dash of Joseph Smith and Mormonism thrown in for good measure, Colavito traces the interwoven histories of the lost race story and the violence of westward expansion to what he calls a Pyrrhic victory, the scientific debunking of the white-mound-builder myth after the so-called Indian Wars of the 19th century. On the whole, Colavito paints a disturbing but compelling portrait of human nature: If the past doesn't justify one's view of one's own race as a superior breed entitled to other people's property and even lives, then one may simply manufacture a brand new history that does.

At times Colavito's analysis is more suggestive than conclusive, but this does little to detract from the book's interest. What is perhaps most unsettling is Colavito's conclusion—a variation on the theme of his 2005 book The Cult of Alien Gods: H.P. Lovecraft and Extraterrestrial Pop Culture. In short, we in the 21st century should not rest on our laurels. We may have rejected the lost-white-race theory, but many of us dismiss the achievements of Native Americans (and others) in a different way, with tales of ancient extraterrestrial influences on Earth's distant past. More broadly, Colavito points out, in "a country where anxieties about social stagnation, terrorism, diversity, and immigration have created racial and cultural tensions, the work of dissenters from historical reality" is often all too effective.

Colavito's conclusions speak to our national capacity for elevating self-deception over facts. The Mound Builder Myth is a work of history, but it is not only about the past. We are still a country turning away not just from Jefferson but from science and reason.

Show Comments (96)