The WHO Is Right To Reject Calls To Ban So-Called 'Wet Markets'

Wet markets should be made safer, not driven underground.

Last week the World Health Organization, which is housed within the United Nations, recommended that governments around the world not shut down markets that sell live animals alongside meat, produce, and other foodstuffs.

These so-called "wet markets," named because they're markets and wet, appear today to be an easy target. After all, evidence suggests the COVID-19 pandemic may have emerged at a wet market in Wuhan, China, that sold live animals alongside meat, vegetables, and other foods.

But these markets are vitally important to people throughout much of the world. And your perception of them and their merits just might be a misperception.

As Quartz notes, these markets, which often operate outdoors, are just common "places where one usually buys groceries," and may differ little or at all from a typical farmers market. "If you have ever been to a shopping area where butchers and grocers sell fresh [meat and] produce straight from the farm, then you have been to something that would, in some parts of the world, be called a wet market," a pair of CNN writers explained last month. I've been to such places—in countries such as Bolivia, Mexico, Tahiti, Curacao, Russia, Spain, and Portugal, and in American cities such as Cleveland, Philadelphia, Seattle, Des Moines, San Francisco, and New York.

Instead of banning wet markets, key WHO leaders are calling instead for better regulation to make them safer for consumers.

"WHO food safety and animal diseases expert Peter Ben Embarek said live animal markets are critical to providing food and livelihoods for millions of people globally and that authorities should focus on improving them rather than outlawing them—even though they can sometimes spark epidemics in humans," the AP reports.

"WHO's position is that when these markets are allowed to reopen it should only be on the condition that they conform to stringent food safety and hygiene standards," said WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus last week, after urging countries in April to close the markets temporarily.

Embarek also suggested several improvements be made to the markets—such as separating live animals from meat and improving waste management practices—which are a key cog in the food chain for many in the developing world.

"They provide fresh and affordable food for millions," Embarek said. "They can be made safe."

Others outside the WHO agree with Embarek and Ghebreyesus.

David Fickling, writing at Bloomberg Quint last month, called on critics to "put the outrage [over wet markets] on pause," noting their importance to many consumers in the developing world. "[F]ar from being cesspits of disease, wet markets do a good job of providing households with clean, fresh produce."

"[B]lanket bans are unlikely to benefit people or wildlife, and are unfeasible because they overlook the complexity of the wildlife trade," four Oxford scholars wrote in a piece that appeared last month in The Conversation. "A more appropriate response would be to improve wildlife trade regulation with a direct focus on human health… especially those involving live animals."

But many others disagree, including Dr. Anthony Fauci, who as head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is helping to coordinate the Trump administration's reaction to the pandemic. "I think we should shut down those things right away," Fauci said last month during a conversation about wet markets.

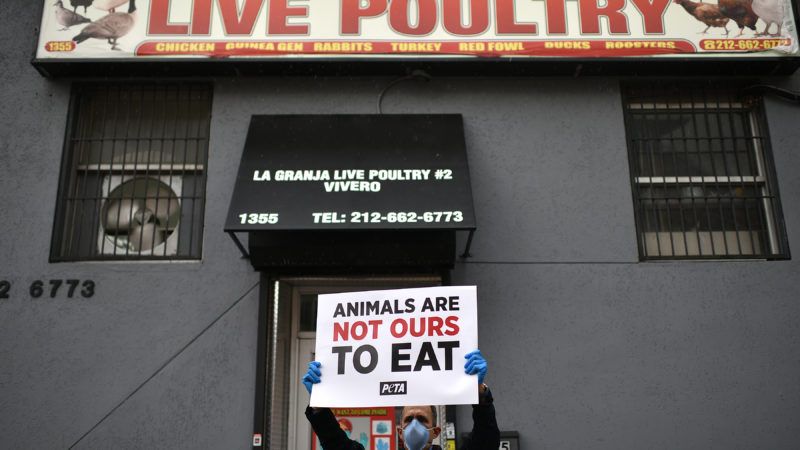

Interesting bedfellows—including PETA, National Review, Bryan Adams, and celebrity gossip site TMZ—have also agreed with Fauci, as do some of Ghebreyesus's and Embarek's own U.N. colleagues. Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, of the U.N.'s Convention on Biological Diversity, said last month that countries should consider banning wet markets.

"It would be good to ban the live animal markets as China has done," she said. But Mrema also sounds a note of caution. "But we should also remember you have communities, particularly from low-income rural areas, particularly in Africa, which are dependent on wild animals to sustain the livelihoods of millions of people."

Is it possible, as the WHO's Embarek claims, both to keep wet markets open for the buyers and sellers who rely on them and ensure the markets don't become the source of the next pandemic? Probably, yes.

I join with the WHO and others in calling for wet markets to remain open (or, as the case may be, to reopen). I also join them in calling for improved market regulation; more widespread hygiene and food-safety training; separating live animals from meat; greater species domestication; banning the sale of diseased or endangered animals (along with some wild and exotic animals); and wider monitoring of both market practices and outcomes.

And to those calling for wet markets to be banned, I ask sincerely that you look around yourself. If placing living animals next to dead ones should be banned, then consider that slaughterhouses—which turn live animals into the meat Americans eat—are home to living and dead animals. Most seafood markets sell live shellfish alongside dead fish. Pet stores sell both living animals and the food they eat. Most farms double as homes, and feature both live animals and their meat. Walmart sold a full array of groceries and live pet fish until discontinuing the latter only last year. You can buy live chickens at some U.S. farmers markets. I could go on.

Placing live animals in close proximity to meat, produce, and other foods is common. It can be dangerous, though it need not be. Wet markets can be both regulated and safe. Banning them would only drive them underground, which would make them unregulated and unsafe and—good intentions be damned—just make the next pandemic much more likely.

Show Comments (66)