Is Marginally Loosening California's Zoning Restrictions Racist?

A new mailer from the AIDS Healthcare Foundation argues that allowing the construction of apartment buildings near transit stops is tantamount to "negro removal."

Is allowing for the construction of more housing near transit stops racist? Most people would say no. Not the Los Angeles-based AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHF), however.

Rather the organization—founded in the 1980s to prevent the spread of HIV and AIDS—had decided to dip their toe into the housing policy debate in California, arguing in a recent mailer that allowing for more housing construction would be tantamount to the racist urban renewal programs of the mid-century.

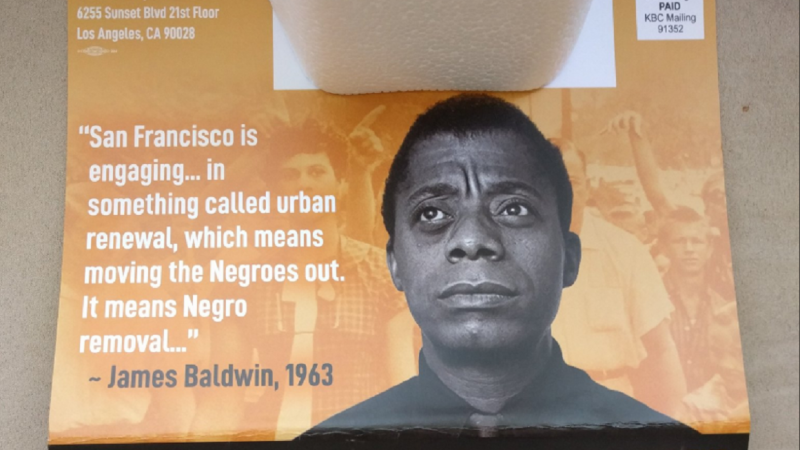

"Urban renewal means negro removal," reads a mailer from the AHF, which also features an image of James Baldwin— a 1960s-era civil rights advocate and novelist. TV ads blaring the same message also aired this week.

— Kyle Huey (@khuey_) April 17, 2019

The target of the mailer is SB 50, a bill that would override local zoning restrictions near transit stops and in wealthy neighborhoods, allowing for taller, denser apartment buildings to be built where now only single-family homes are allowed.

Doing so, say advocates, will boost the supply of housing, helping to make the Golden State's incredibly pricey cities a little more affordable and, by extension, a little more inclusive.

Not so says the AHF, which argues that deregulating housing construction along the lines of SB 50 will benefit the rich at the expense of poorer, minority communities.

"SB 50 is a handout to greedy developers," reads the AHF mailer, which goes on to say that the bill would these developers "free rein to displace working class communities of color."

The argument that loosening California's restrictions on new housing construction will result in gentrification of minority neighborhoods as "luxury condos" replace older, more affordable housing stock, is hardly unique to AHF.

Indeed, this criticism has dogged most any attempt to peel back zoning restrictions legislatively, and is often employed to stop individual projects working their way through local planning processes as well.

AHF's mailer is unique, however, both in how bluntly it makes this case against SB 50, and in how many untruths it spreads about the bill.

For example, the AHF's mailer says that "SB 50 bans cities from rejecting big residential luxury developments containing only a small number of affordable units."

This is a reference to many cities' "inclusionary zoning" policies which require that private developers designate a certain percentage of new units in a projects as "affordable"—meaning they are rented out at below market rates to people earning less than an area's median income.

Regardless of the wisdom of these inclusionary zoning requirements (which some research suggests reduces the supply of new housing), this claim is simply untrue.

SB 50 requires that any housing project that benefits from its upzoning provisions, and is larger than 20 units, include somewhere between 15 to 25 percent affordable units. And contrary to AHF's claims, the law includes an explicit provision saying that local governments could impose higher affordability requirements should they wish.

Reads an analysis of the bill prepared by state Senate committee staff, "if the local government has adopted an inclusionary housing ordinance and that ordinance requires that a new development include levels of affordability in excess of what is required in [SB 50], the requirements in that ordinance shall apply."

The rest of the mailer is more hyperbole than outright falsehoods, calling SB 50 a "trickle-down housing bill" that would "accelerate the consequences of gentrification" and "build luxury towers without adequate affordable housing."

That argument is deeply ironic coming from AHF, given the group's past support for a policy that is known to spur gentrification: rent control.

Back in 2018, AHF spent some $21 million advocating for Prop. 10, a ballot initiative that would have repealed state-level limitations on the ability of California's local governments to impose rent control.

A Stanford University study from the same year found an expansion of rent control in San Francisco during the '90s actually sped up gentrification by encouraging landlords to take rent-controlled housing units off the market and convert them into pricier condominiums that could be sold at market price.

Were AHF truly as concerned about gentrification as their noxious mailer suggests, they might want to reconsider their past rent control advocacy as well. Instead the group had decided to cynically deploy identity politics in an effort to spread myths about what is, at the end of the day, a marginal loosening of California's ridiculously restrictive zoning laws.

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Show Comments (39)