Aluminum Tariff Tradeoff: 300 Jobs for $690 Million in New Taxes

New study argues the tariffs have boosted employment, but doesn't examine the costs of President Donald Trump's protectionism.

If you ignore the fact that tariffs are taxes, it's pretty easy to make tariffs look good.

That's what a report released this week by the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), a union-backed think tank, tries to do. By ignoring the costs of higher taxes on imported aluminum, the EPI study claims that President Donald Trump's aluminum tariffs have created about 300 jobs at American aluminum manufacturers. In addition, the report claims, American aluminum suppliers and processors have made more than $3 billion in economic investments since the tariffs were imposed—including the restarting of three smelters that had previously been closed—investments that could, eventually, create as many as 2,000 additional manufacturing jobs.

"We found absolutely no evidence of broad, negative impacts on the economy of steel and aluminum tariffs to date," Robert E. Scott, EPI's senior economist, told CNBC, which trumpeted the pro-tariff study on Tuesday under a headline proclaiming that "steel and aluminum tariffs are not hurting the economy."

If that's the case, Scott and his colleagues must not have been looking very hard. No, I'm not talking about the literally hundreds of companies that have reported economic problems caused by the Trump administration's tariffs—although they matter too.

The bigger flaw in the EPI study is that it fails to account for the costs of the tariffs. Those 300 new jobs didn't just spring up out of nowhere because the president said some magic words—they are the result of businesses shifting resources and strategies in an economic environment where imported aluminum has suddenly been subjected to a 10 percent tax increase. In other words, the trade-offs (in this case, the higher taxes) matter.

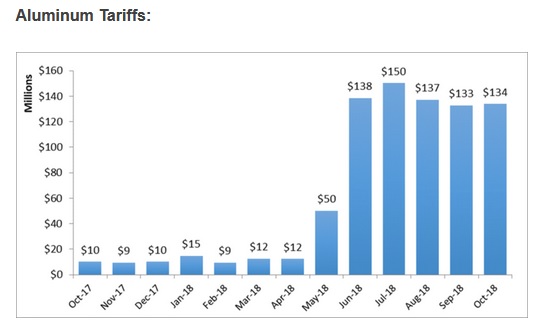

And the trade-offs are huge. Since the aluminum tariffs were imposed on June 1, American companies have paid about $690 million in tariffs to the federal government, according to data from The Trade Partnership, a pro-trade nonprofit, and Tariffs Hurt the Heartland, which is lobbying for Congress and the administration to remove those tariffs.

Do the math. That means those 300 jobs have cost about $2.3 million each. That's insane. Even if you give EPI the benefit of the doubt and assume that those 2,000 additional manufacturing jobs eventually come online, we're still talking about a price tag of about $300,000 per job.

It's no surprise that the tariffs have given a modest boost to American aluminum plants, but economists have warned for months that the economic consequences of Trump's protectionist trade policies would far outweigh the benefits. Shortly after the steel and aluminum tariffs were imposed, The Trade Partnership predicted that the number of jobs in American steel- and aluminum-producing industries would increase by about 26,300, while tariffs reduced employment in the economy as a whole by about 429,000. That's 16 jobs lost for every job gained.

Thanks to the 10 percent tariff on aluminum, a 25 percent tariff on steel, and additional tariffs on more than $200 billion of Chinese-made goods, Americans ended up paying $6.2 billion in import taxes in October, making it the most expensive tariff month in American history, according to Tariffs Hurt the Heartland.

Those taxes are a significant drag on the economy, even if they do spur a low-level of job creation in certain domestic industries. Like the proverbial case of the broken window, it's relatively easy to see the new jobs created by the tariffs—but the unseen costs, like the jobs that are lost or never created in the first place because of the higher import taxes, matter too.

The EPI report highlights the positive consequences of Trump's tariffs while refusing to look at the negatives. That's something I'd expect from the White House, but not from supposedly serious economists.

Show Comments (42)