The Federal Government's Finances Are a Total Wreck

And the biggest liabilities don't even appear on the official balance sheet.

The federal government's latest financial statements came out last week and they paint a dire picture of our nation's fiscal health. It's not just the annual deficit, which is too large and growing. The new report shows trillions in long-term liabilities that could burden the country for years to come. And it suggests that financial management in large government agencies, like the Department of Defense, is appallingly poor.

The federal government reports assets of $3.5 trillion and liabilities of $23.9 trillion yielding a negative net position of $20.4 trillion. Although this last amount is similar in size to the national debt, net worth is conceptually different.

Federal audited financial statements use accrual accounting, which means that obligations are recognized as they are incurred. For example, the $23.9 trillion in liabilities includes $7.7 trillion in veterans benefits and retirement benefits earned by federal civilian employees. Another $200 trillion in liabilities arise from various guarantees the government has made, including its commitment to backstop private pension plans—many of which are becoming insolvent.

But the biggest federal liabilities of all do not appear on the government's balance sheet. According to a supplemental schedule, the federal government has $49 trillion in Social Security and Medicare liabilities. Although these retirement obligations are just as politically sacrosanct as federal employee pensions and federal guarantees for private pension systems, they receive very different accounting treatment. If these obligations were placed on balance sheet where they belong, the government's negative net position (i.e., its unfunded debt) would balloon to $69 trillion—well over triple the nation's $19 trillion gross domestic product.

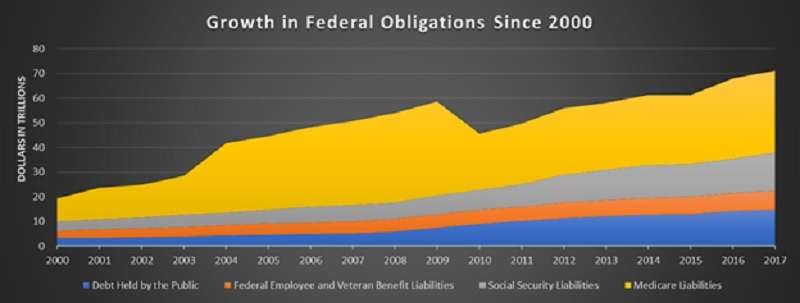

As the accompanying chart shows, the federal government's net position has been deteriorating throughout the 21st century. The only apparent bright spot occurred in 2010 when actuaries bumped down Medicare liabilities amidst optimism about Obamacare's prospects for reining in medical costs—a hope that has not fully panned out. The big spike between 2003 and 2004 was largely the result of George W. Bush's unfunded Medicare prescription drug benefit.

Although the government's fiscal year 2017 deficit was an already alarming $666 billion, its balance sheet net position worsened by over $1.1 trillion. Social insurance obligations increased a further $2.3 trillion. So, while the government added less than $700 billion in red ink during fiscal year 2017 on a cash basis, the total bleeding in accrual terms was closer to $3.4 trillion. Just as accountants and regulators insist that corporations use accrual accounting to properly inform investors about their financial condition, we should have similar expectations for sovereigns such as the federal government.

Even worse, the chart doesn't include all federal liabilities. Government financial statements exclude $5 trillion in outstanding mortgage backed securities issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) were placed under federal conservatorship during the financial crisis. Although the federal government owns 79.9% of each of these entities and would undoubtedly cover any shortfalls they experience with taxpayer money (as they did in 2008), their liabilities are not consolidated onto the federal government's balance sheet.

Finally, it is worth noting that the 2017 federal financial statements—incomplete as they are—received a negative audit opinion, as they do every year. Specifically, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) acting in its role as the federal government's CPA concluded:

The federal government is not able to demonstrate the reliability of significant portions of the accompanying accrual-based consolidated financial statements as of and for the fiscal years ended September 30, 2017, and 2016, principally resulting from limitations related to certain material weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting and other limitations affecting the reliability of these financial statements.

The GAO reported favorable opinions for most of the federal departments it reviewed, but the Department of Defense (DOD) remains problematic. The GAO found weaknesses in the DOD's cost reporting and its accounting for plant, property and equipment.

These findings invite the question of whether the DOD can effectively manage all the new money Congress and the Administration are giving it. If Pentagon accountants don't really know what the department owns and can't document what the military establishment is spending, what assurance do we have that all the extra tax money it is about to receive won't be wasted?

It is unfortunate that each year's federal financial statements do not receive more attention. Any company reporting results like those the government reported last week would face liquidation. Any state or local government reporting such a lopsided balance sheet would lose access to the municipal bond market. While the federal government enjoys a special status because it can lean on the Federal Reserve to buy its bonds with newly created money, that money printing capability can only go so far.

If the bleeding doesn't stop, we should expect investors in Tresasury securities to demand higher rates as the perceived risk of not being paid on time, in full and with uninflated dollars increases. With over $14 trillion in publicly held debt already on the books and trillions more being added in the coming years, federal interest costs will mount placing added pressure on the budget. At some point, the nation could face a sovereign debt crisis with serious global consequences.

Show Comments (22)