The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

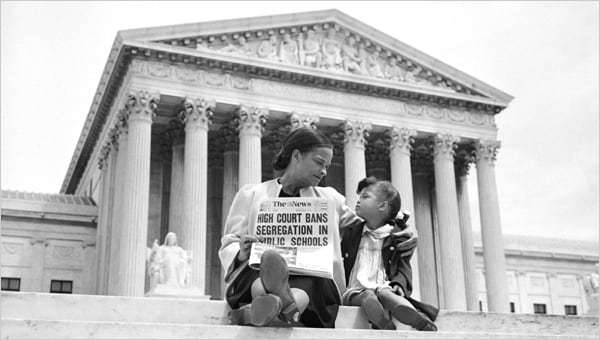

Democracy and Brown v. Board of Education

In her seriously flawed recent book Democracy in Chains, historian Nancy MacLean argues that James Buchanan and many other libertarians are anti-democratic and that their supposed opposition to Brown v. Board of Education helps prove the charge. The idea that Buchanan and other leading libertarian thinkers of the day supported segregation and opposed Brown is based on crude misreading of evidence and utterly indefensible. In addition, as various critics (including myself) pointed out, it is strange to claim that opposition to Brown is an indicator of opposition to democracy, given that Brown and other anti-segregationist court decisions struck down policies enacted by the democratic process and supported by political majorities in the states that adopted them. Indeed, Brown invalidated government policies heavily influenced by ignorance, prejudice, and the tyranny of the majority - all reasons that libertarian thinkers have long cited as justifications for limiting the power of democratic processes in a range of settings.

In an interesting recent essay, historian Lawrence Glickman concedes that there are flaws in MacLean's analysis, but tries to resuscitate her claim that opposition to Brown is anti-democratic. Glickman's argument is better-reasoned than MacLean's own. But it still largely fails. To the extent it might succeed, it does so by redefining democracy in a way that leads to conclusions left-liberal critics of libertarianism are unlikely to be happy with. The issues Glickman raises are important for reasons that go well beyond the debate over MacLean's book. They have broader implications for the relationship between democracy, liberty, and judicial review.

I. Why Brown was Countermajoritarian.

Glickman correctly points out that many of the segregationist policies struck down by Brown were enacted in states where African-Americans did not have the right to vote, thereby casting serious doubt on those policies' democratic credentials. This is true, but not enough to refute the conclusion that Brown was a countermajoritarian decision constraining the democratic process. I covered this issue in my earlier post on the subject:

A consistent majoritarian democrat should be against Brown. After all, that decision struck down important public policies enacted by elected officials and strongly supported by majority public opinion in the states that adopted them. In fairness, those states were not fully democratic because they denied the franchise to African-Americans. Had blacks been able to vote at the time, Jim Crow segregation would surely have been less oppressive. But a great many segregation policies would likely have been enacted nonetheless, since blacks were a minority and the white majority in those states was strongly racist. The Brown case itself actually arose in [Topeka,] Kansas, where blacks did have the vote, but still lacked sufficient political clout to prevent the white majority from enacting school segregation.

Glickman notes that, by the time it reached the Supreme Court, Brown was combined with several other desegregation cases that arose in places where blacks did not have the right to vote at the time. True. But the inclusion of the Topeka case is still significant because it shows that segregation could arise even in places where African-Americans did have the right to vote, and that the civil rights movement believed that judicial intervention in such cases was entirely appropriate.

There is also a broader point to be made here. The position advocated by the civil rights movement in cases like Brown and ultimately endorsed by the Supreme Court was not that segregation should only be struck down in areas where African-Americans were denied the right to vote or those where the policy lacked majority public support. It was that such race discrimination is unconstitutional and should be invalidated by unelected judges regardless of how much support it might have from majority public opinion or elected officials. That is what ultimately makes Brown and other similar decisions constraints on majoritarian democracy, rather than judicial attempts to reinforce it. The same is true of a great many other judicial decisions favored by left-liberals that cannot be readily justified as merely helping to ensure that everyone is able to participate in the democratic process.

II. What if Democracy Entails Giving Everyone "a Say in the Decisions that Affected their Lives"?

It is possible to resist this conclusion by defining "democracy" in broader terms. And that's exactly what Glickman does. In his view, the essence of democracy resides "not only in one person/one vote and in constitutional protections for minorities but in the necessity for all people to have a say in the decisions that affected their lives."

Much depends on exactly what it means for people "to have a say in the decisions that affected their lives." If it merely means having some minimal opportunity to participate in the decision-making process, then African-Americans in 1950s Topeka had enough "say" to qualify. After all, they, like whites, could vote in local elections that decided who would get to direct education policy. True, they rarely actually prevailed on issues related to segregation. But repeated defeats are a standard part of the political process, especially for unpopular minorities.

But perhaps "having a say" means more than just the right to participate, but actually requires people to have a substantial likelihood of influencing the outcome. In that sense, blacks in Topeka obviously did not enjoy true "democracy." But their painful situation was just an extreme case of a standard feature of electoral processes. In all but the smallest and most local elections, the individual voter has only an infinitesimal chance of actually influencing the result, about 1 in 60 million in a US presidential election, for example. A small minority of citizens have influence that goes well beyond the ability to cast a vote - politicians, influential activists, pundits, powerful bureaucrats, important campaign donors, and so on. But the overwhelming majority do not.

If having a say means having substantial influence over the content of public policy, most of us almost never have a genuine say. Obviously, most voters are not as dissatisfied with the resulting policies as African-Americans in the 1950s had reason to be. But that is largely because their preferences and interests happen to line up more closely with the dominant political majority, not because they actually have more than infinitesimal influence.

Perhaps you "have a say" if enough other voters share your preferences that the government is forced to follow them. But in that event, the government is still enacting your preferred policies only because powerful political forces advocate for them, not because you have any significant influence of your own. In the same way, a person who agrees with the king's views might be said to "have a say" in the policies of an absolute monarchy. And if, as Glickman suggests, the goal is to give "all people" a say (emphasis added), then any electoral process will necessary leave many people out. There are almost always substantial minorities who strongly oppose the status quo, but have little prospect of changing it.

The powerlessness of the individual voter is one of the reasons why many libertarians favor making fewer decisions at the ballot box and more by "voting with your feet." When making choices in the market and civil society, ordinary people generally have much greater ability to make decisive choices than at the ballot box. When you decide what products to buy, which civil society organizations to join, or where you want to live, you generally have a far greater than 1 in 60 million chance of affecting the outcome. Whether or not it is more "democratic" than ballot box voting, foot voting gives individuals greater opportunity to exercise meaningful choice.

Taking the "having a say" standard seriously also entails cutting back on the powers of government bureaucracies. The latter wield vast power over many important aspects of people's lives, often without much constraint from either foot voting or ballot box voting.

If having a meaningful say is the relevant criterion, it also turns out that James Buchanan's advocacy of school choice - wrongly derided by Nancy MacLean as an attempt to promote segregation - is more "democratic" than conventional public schools. In the case of the latter, most individual parents have very limited ability to influence the content of the public education available to their children. They can only do so in the rare case where they can exercise decisive influence over education policy, or by moving to a different school district. By contrast, school choice enables them to choose from a wide range of different options, both public and private. And they can do so without having to either move or develop sufficient political clout to change government policy.

This advantage of foot voting does not by itself justify either libertarianism generally or the specific policy of school choice. It also does not by itself prove that we should cut back on the bureaucratic state. Perhaps conventional public schooling, massive government bureaucracy, and other similar institutions can be justified on grounds unrelated to giving people a say. But it does highlight how the ideal of "having a say in decisions that affect you" has implications that cut against policies embraced by many left-liberals.

Glickman also briefly mentions arguments that segregated schools were undemocratic because they impeded development of the "capacities" of citizens for political participation. It is certainly true that argument was made at the time. But Brown did not rule that segregated schools were only unconstitutional in cases where they left African-Americans students with poorly developed political capacities, and later decisions building on Brown struck down segregation in situations far removed from education and capacity development.

There is, of course, one other sense in which Brown might be democratic, after all. In public discourse, "democratic" is often lazily used as a synonym for "good" or "just." Whether or not it is linguistically correct, this usage is not analytically useful. It essentially effaces the distinction between democracy and other seemingly good political values, and defines away the possibility that democracy might ever be bad in any way.

In sum, Brown is best understood as a constraint on democracy, unless the latter is expansively defined as having a genuinely meaningful say over government policy, or as synonymous with whatever is good and just.

Show Comments (0)