The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Libel takedown injunctions and fake notarizations

I've blogged before about people getting injunctions against alleged libelers, aimed solely at getting Google to deindex the allegedly libelous page. The injunctions aren't gotten with any expectation of the alleged libeler voluntarily complying, or of the alleged libeler being forced by the court to comply. Rather, Google has a policy that it will often remove pages from its indexes once it sees an injunction finding the pages to be libelous; and that's what the plaintiff wants.

It's understandable that many plaintiffs would legitimately seek such a remedy, and that Google would offer it. Traditional libel damages awards are useless when defendants lack money, and court enforcement of injunctions is useless when the defendants are effectively anonymous, or overseas, or are unable to remove the libelous material (for instance, from sites such as RipOffReport, which doesn't allow people to remove their own posts).

But one danger with this practice, as we've seen, is that it leads to an incentive for unscrupulous people - whether plaintiffs, their lawyers or reputation-management companies hired by the plaintiffs (and potentially working out the details without the plaintiffs or the lawyers' knowledge) - to file lawsuits against fake defendants. The fake defendant supposedly submits a document agreeing to the injunction. (In reality, the document is provided by the same reputation-management company that is acting on behalf of the plaintiff.) The court believes that both sides agree to the order, so it issues the order. And then Google sees the order, and often acts on it.

One possible means of preventing the fake-defendant lawsuits, of course, is to try to make sure that the defendant is real; and one obvious solution to the problem is to have the signature verified by being notarized. But who will verify the existence of the verifiers?

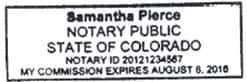

Consider Chinnock v. Ivanski, a case in which the complaint identified the defendant as "an individual who resides in Turkey." But on the Amended Order for Permanent Injunction, the defendant's signature was notarized by a Samantha Pierce of Colorado, and here is a copy of her notary stamp:

20121234567 appears suspicious, and in this instance appearances do not deceive: There is no Samantha Pierce listed on the Colorado notary site, with that notary ID or any other. (I posted this order Tuesday, as a little puzzle for our readers; this post is the promised explanation.) The notary ID 20121234567 and the expiration date Aug. 8, 2016, are the placeholders shown by the Colorado secretary of state in explaining to notaries what format they should use for their seals.

And that's not all; on the earlier, pre-amended Stipulated Order for Permanent Injunction in the same case, the notary for Ivanski's signature is Amanda Sparks of Fulton County, Ga. Again, there is no Amanda Sparks of Fulton County on the Georgia notary website; there is an Amanda Sparks in a different county, but with a different expiration date.

Similarly, in Lynd v. Hood, the notary listed for the defendant's signature is Jose Garcia from Harris County, Tex., and his license is said to expire on March 2, 2016. However, there is no Jose Garcia listed on the Texas notary website with the same license expiration date. Chinnock v. Ivanski and Lynd v. Hood were filed by lawyers Daniel Warner and Aaron Kelly, of Kelly/Warner PLLC. (Both lawyers' names appear on some court documents in each case; the court docket shows Warner as the lawyer of record on Chinnock, and Kelly as the lawyer of record on Lynd.) Warner was also the beneficiary of one of the Richart Ruddie-linked orders that fit the pattern discussed in this post - that's what led me to look closely at the Chinnock order - though the exact connection between Warner and Ruddie is unclear.

It is also unclear who was responsible for the apparently inauthentic notarizations, and who knew about them. It is possible, for instance, that they were the work of some reputation-management company that connected the plaintiffs and Kelly/Warner, and that the company claimed that it had gotten the documents authentically signed and notarized. I reached out to the Kelly/Warner people about this, but they would not respond on the record.

The private investigator who has been helping me (Giles Miller of Lynx Insights & Investigations) couldn't find the ostensible Lynd v. Hood defendants, Connie Hood and Jesse Wood, at the addresses given for them; nor could he find any evidence of the existence of Krista Ivanski, of Chinnock v. Ivanski; nor could he find Jake Kirschner, the ostensible defendant in Ruddie v. Kirschner, the case aimed at deindexing a RipOffReport post about Daniel Warner; nor Howard Marks, the defendant in Gottuso v. Marks, another Kelly/Warner case (though one without a notarization). It's possible, of course, that the relevant public records are incomplete, and that each of these people was associated with the address for too short a time to make it into such records. Still, the overall pattern, coupled with the suspicious notarizations, suggests that at least some of these orders are untrustworthy.

Show Comments (0)