Bureau of Prisons Will Reduce Time Inmates Spend in Controversial 'Double Solitary'

News investigations have found that putting inmates together in cells the size of a parking space for 23 hours a day, shockingly, doesn't end well.

The federal Bureau of Prisons announced Friday that it will curtail its practice putting dangerous inmates in cramped cells together for up to 23 hours a day, a practice paradoxically known as "double-cell solitary."

The agency, as part of the Obama White House's directives earlier this year to reduce the use of solitary confinment, said it will now require mental health screenings before placing an inmate in what's known as its Special Management Unit, which is meant to hold gang leaders, violent inmates, and others considered too dangerous for the general prison population. Time in SMU will be limited to two years, with the goal of getting most inmates out within one year, and, the agency said, it will no longer release inmates straight from SMU back out into society.

Solitary confinement is often described as a tiny slice of hell, but arguably more hellish, as Jean-Paul Sartre once famously observed, is being trapped with another person. Civil liberties advocates argue the practice of putting two inmates, many times violent or mentally ill or both, in a 6x10 foot cell for up to 23 hours almost day ensures they will become more violent, more ill, or both.

"We're placing people in SMU who are supposed to have behavioral problems," Amy Fettig, the senior counsel for for the ACLU's National Prison Project, said in an interview. "But then we're placing them in a cell the size of your bathroom with another person for 12 months. That type of arrangement sets up people to be injured, if not worse."

As the Marshall Project reported earlier this year, at least 18 states double-up their restrictive housing unit cells, more than 80 percent of the 10,747 federal prisoners in solitary have a cellmate, and the consequences are often deadly:

One prisoner, Aaron Fillmore, started feeling an unexplainable aggression towards his cellmate. "It was a level of discomfort that I never experienced before," he wrote in a letter. Fillmore was double celled at Lawrence Correctional Center in Illinois for three months. "I had thoughts of just punching him in the face. Why? I have no idea. I just had the urge to do it."

In 2013, an Ohio man suffering from psychotic delusions strangled his cellmate a day after they were placed together. The murdered cellmate was two days away from being released. A prisoner in Georgia stabbed his cellmate multiple times in 2014 as officers were handcuffing that cellmate through the cell door. When guards demanded that the prisoner put his hands up to be cuffed, he yelled in response, "I can't do that. He just kept messin' with me." That same year in Alaska, two cellmates who had been friends got into an argument, which ended when one strangled the other. After realizing what he had done, he screamed for the guards' help.

Fettig and other civil liberties advocates say the reforms are a step in the right direction, but still far above international standards for solitary confinement. A United Nations expert on torture has called for solitary confinement over 15 days to be completely abolished.

And, Fettig said, although inmates in SMU are not technically in solitary, "what we hear from mental health experts is it's still an extreme level of isolation even if you're with another person. The mental health impact is very, very similar. You're likely to see the mental and cognitive degradation that occurs in severe isolation."

Alan Mills, the executive director of the Uptown People's Law Center in Chicago, a nonprofit legal aid organization, said "double celling does not relieve the damage done by solitary."

"To the contrary, it makes it worse," he continued. "People confined to solitary develop coping mechanisms--constant pacing is one, very strict routines is another. Having a second person, always present, in a very small space with zero privacy, interferes with these coping mechanisms--and one person's coping mechanism is another person's irritant."

In 2014 Mills documented two inmates confined to double-cell solitary in an Illinois state prison who had developed bed sores from lack of movement.

For now, civil liberties advocates are waiting to see how the new policies will actually play out.

"What is in writing is not always what is implemented on the ground," Fettig said, "and in a vast system like the Bureau of Prisons, we're going to have to see rigorous oversight, otherwise it's just a piece of paper."

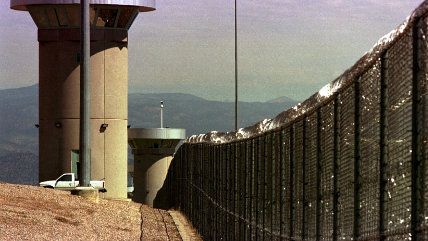

The Lewisburg federal penitentiary currently has the largest SMU in the country, housing more than 1,000 inmates. As Fusion reported on Friday:

Constructed in the 1930s, Lewisburg was a model of prison reform. Inmates lived in a building designed to look like a college campus, and participated in programs like a prison newspaper and a farm where they grew their own crops. But over the years, the facility got more and more restrictive. Starting in 2009, most of the prison was transformed into an SMU. It's billed by the Bureau of Prisons as a rehabilitation program, a way to make the worst of the worst inmates—gang leaders and inmates with extreme disciplinary records—more manageable. Among prisoners around the country, however, it's a source of fear […]

One inmate, Sebastian Richardson, said in a lawsuit filed in 2011 that he was assigned to be a roommate with another prisoner—nicknamed "The Prophet"—who had assaulted about 20 people while in prison. When Richardson refused his roommate assignment, he said he was placed in hard restraints for a month. (Five years later, the case is still pending.)

In a press release, the Bureau of Prisons said "the SMU program is one of the tools available to staff to ensure a safe and orderly environment at all institutions and to address unique security and management concerns."

Show Comments (19)