Donald Trump and the GOP's National Status Anxiety

Last night's GOP presidential debate was, overall, rather light on coherent policy detail, but it served as an effective confirmation of the Republican party's priorities in 2015: policing the border more heavily and punishing undocumented immigrants who are already here, bolstering the nation's military strength, attacking the Islamic State, taking a harsher tack when dealing with other world leaders, and, in general, adopting a more openly aggressive stance on foreign affairs. Domestic policy issues like tax reform did arise, and were haltingly ping-ponged across the stage, but on the whole, the debate saw many of the party's potential standard-bearers emphasizing its hawkish, nativist impulses whenever the opportunity presented itself.

In the process, what the debate revealed, perhaps more than anything else, was the GOP's deep-seated, occasionally verging on apocalyptic, anxiety about America's place in the world—and its dwindling status in the eyes of the party's own faithful.

On more than one occasion last night, this point was made explicitly. The next president must ensure that the "world will know that the United States in America is back in the leadership business," said Carly Fiorina. "America needs a leader who will go big and bold again," said Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker. "I believe that we need to restore America's presence and leadership in the world," said former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush.

Implicit in these statements is that idea that America has not only lost stature abroad, but that it has failed to live up to its promise at home as well. At times, that sentiment was spelled out directly as well, as in New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie's opening statement, which warned that under President Obama, the nation has lost the "belief that the next generation will have a better life" and Texas Sen. Ted Cruz's promise to "reignite the promise of America" within its borders.

What's notable in these statements, and others like them in the debate, is that they describe not what the candidates would do as president, but what America would be.

All throughout the evening, and indeed through the campaign, the GOP candidates have conveyed, to varying degrees, a non-specific sense of uneasiness, and at times even anger, about America's status and identity, relying on a shared sense that America is no longer the glorious institution that it was at some point in the past. Some of this is just the inevitable rhetoric of a party that has been out of the White House for seven years. but it's common enough to leave the impression that most of the GOP candidates believe this to be the overriding problem facing the next president. The suggestion seems to be that the chief business of the next president should be to arrest the nation's perceived decline in standing at home and abroad.

At times last night, this idea manifested as an even broader sense that not only only is America's reputation at stake, but that America's decline inevitably entails the decline of the rest of the larger western world. The phrase "Western civiliation" was uttered six times last night—four times by Ohio Gov. John Kasich, mostly in reference to the conflict in Syria, and twice by Mike Huckabee, who warned that "the survival of Western civilization" was at stake in America's dealings with Iran. In this view, both America and the rest of the world are poised on the edge of an abyss, ready to plummet at any moment into darkness.

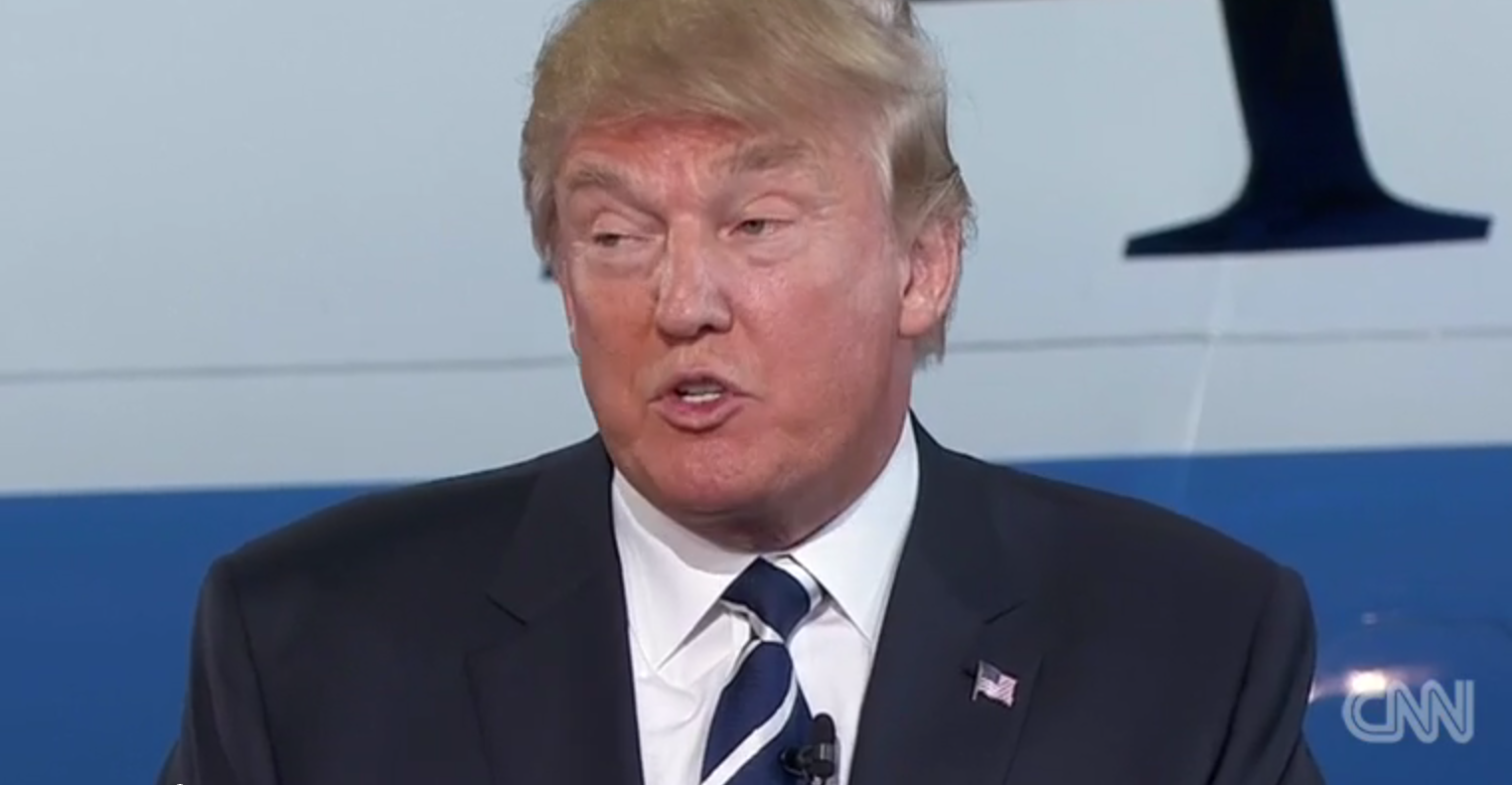

In this loss-charged environment, it is perhaps no surprise that the most successful GOP candidate of the race so far, Donald Trump, has run a campaign that is not merely light on policy specifics, but actively disdainful of them, and that his oft-repeated slogan is simply, "Make America great again."

For Donald Trump's supporters, what Trump would do as president is far less important than the character improvements he would impart to the nation simply by virtue of winning the presidency.

Trump, more than any other candidate, has effectively capitalized on the GOP base's pervasive sense of unease about America's character and status. In the process, however, he and his supporters exacerbated the character flaws in the Republican party, playing up and encouraging some of its most unpleasant and off-putting elements—its merciless nativism, its unyielding hawkishness, its persistent anti-intellectual bent. And in the process he threatens to do lasting damage to a party whose reputation is already in the dumps, reaching its lowest levels in more than two decades earlier this year.

At this point, there is clear (and entirely unsurprising) evidence that Trump has harmed the party's already-low reputation with Latinos and immigrants. There is good reason to believe that Trump, who has repeatedly demeaned women based on their looks, will further turn off women from the party as well. Many Europeans, meanwhile, appear to view Trump largely as a boorish joke—an icon of ignorance and vulgarity who reflects poorly not just on the GOP but on the nation.

At home and abroad, Trump is hurting both the GOP and the country that GOP leaders insist they want to rescue. Which suggests that before trying to rescue Western civilization; Republicans should probably try to salvage their own party first.

Show Comments (112)