Surviving Nagasaki

History, memory, and nuclear devastation

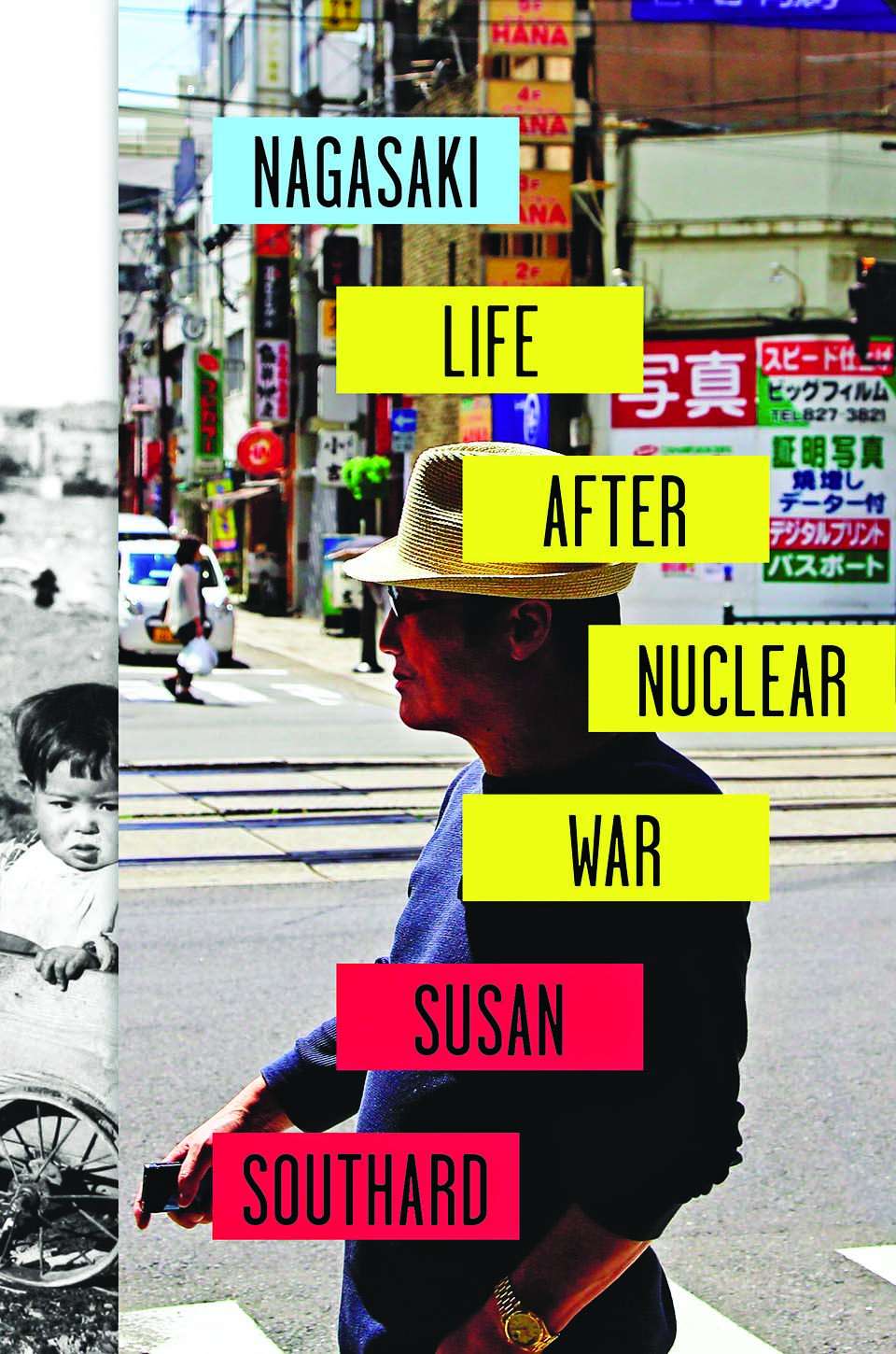

Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War, by Susan Southard, Viking, 416 pages, $28.95

When the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki at the end of the Second World War, Yoshida Katsuji was horrifically injured. "Like everyone else in Nagasaki that day," Susan Southard writes, his "immediate survival and degree of injury from burns and radiation depended entirely on his exact location," the direction he faced, his clothing, and which buildings and natural structures stood between him and the blast. Half a mile away from the explosion, Yoshida saw the skin from his arm "peeled off and was hanging down from his fingertips." "Blood was pouring out of my flesh," he recalls.

Do-oh Mineko's story is even more gruesome. The "whole left side of her body was badly burned, a bone was sticking out of her right arm at the elbow, hundreds of glass splinters had penetrated most of her body, and blood was streaming down her neck," Southard reports. There was a "wide and deep horizontal gash stretching from one ear to the other, filled with shards of glass and wood." By candlelight and without anesthesia, a doctor removed hundreds of glass shards and splinters from her body and head as she screamed all night, praying to die.

The immediate aftermath of days and weeks did not bring an end to the pain and suffering. A decade after the war, Southard notes, survivors still suffered "blood, cardiovascular, liver, and endocrinological disorders, low blood cell counts, severe anemia, thyroid disorders, internal organ damage, cataracts, and premature aging." They were routinely rejected as suitors for marriage. They faced an extreme and often unobtainable burden of proof to secure access to the health examinations provided to survivors under the 1957 Atomic Bomb Victims Medical Care Law. Yoshida's children endured the shameful predicament of telling their friends what had happened to their father's face.

Even the nearly instantaneous destruction of hundreds of thousands of lives can become somewhat lost in a war where 60 million people, mostly civilians, died. In Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War, Southard, who holds a degree in creative nonfiction, focuses on five survivors, tracking their post-bomb lives and consulting hundreds of other primary and secondary sources.

In addition to Yoshida and Do-oh, Southard describes the fates of Nagano Etsuko, Taniguchi Sumiteru, and Wada Koichi, "among the select few who keep the public memory of the atomic bomb alive." These survivors' memories lend texture and depth to the book, which is built on a solid framework of scholarly literature. Theorists of history should find interest in the tricky methodological balance Southard strikes.

Southard is up against collective memory. She cites a 1995 Gallup poll finding that one-fourth of Americans had no knowledge of the atomic bombings and that few understood their severity. Looking not just at the bombing and its aftermath, but at the memory of that history, Southard examines the institutional factors that shaped public understanding. General Douglas MacArthur's censors, who required the preapproval of press publications in occupied Japan to prevent "false or destructive criticism of the Allied Powers," rejected Chicago Tribune journalist George Weller's reports on the devastation. The U.S. government, whose scientists had "conducted no studies on the potential effects of high-dose, whole-body radiation exposure on the people of Japan," tried to control the scientific determination of what had happened. More than 8,000 Americans and Japanese worked in the Civil Censorship Detachment, which monitored media, personal correspondence, and telecommunications. In 1945, the United States confiscated Japanese researchers' "early blood samples, specimens, photographs, questionnaires, and clinical records from victims' autopsies and survivors' examinations."

The United States had an interest in rationalizing the bombings. In the wake of the war, Americans read about how many lives the bombs supposedly saved. Karl T. Compton, president of MIT, wrote a December 1946 Atlantic piece estimating that the bomb had saved "hundreds of thousands—perhaps several millions" of Americans and Japanese from perishing in a prolonged war. Former Secretary of War Henry Stimson presented similarly high estimates, neglecting to mention the fraught debates among top officials over the U.S. demand for unconditional Japanese surrender and other complicating facts. Meanwhile, American officials censored publications on the bombings, forcing a U.S.-written appendix that highlighted Japanese atrocities onto Takashi Nagai's 1947 book The Bells of Nagasaki. America's nuclear build-up in the early Cold War made officials all the more guarded against bad publicity for this new weapon of war. It wasn't until 1967 that the United States finally sent footage of the post-bombing wreckage back to Japan.

Struggle over memory also transpired within Japan, where the bombing's meaning was highly contested. In 1969 Tatsuichiro Akizuki, a Nagasaki-based doctor, launched the Nagasaki Testimonial Society, calling on written records of first-hand experience with the ultimate goal of abolishing nuclear weapons. The project gave voice to survivors frustrated with the hesitance of the Japanese government, now allied with the United States, to condemn the bombings, and with official textbooks that minimized their calamity in an effort to rehabilitate Japanese nationalism.

According to a 2015 Pew Research Center poll, 56 percent of Americans consider the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki justified. The U.S. government's active attempts to limit public revulsion in the bombings' immediate aftermath appear to have had a lasting effect. But even those who think the use of the atomic bomb against Japan was the right choice must still face the scope of destruction and the generations of suffering that rippled out from the detonations in Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

Southard's book is an invaluable tool for that task. The instantaneous death of hundreds of thousands of people in August 1945—and the possible deaths of millions or billions more in a future nuclear war—are imbued much more meaning and immediacy by the personal glimpses that Southard provides.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Surviving Nagasaki."

Show Comments (7)