Rolling Stone and the Cult of Credulity

The mantra 'I believe' pathologizes skepticism and doesn't help victims.

Now that Rolling Stone has retracted its University of Virginia gang-rape story—a piece of penny-dreadful writing dolled up as journalism—the hunt is on for the culprit in this fiasco. Who's to blame for the appearance of what seems to be straight-up fabulism in the pages of a once-respectable magazine?

Some are blaming "Jackie," the pseudonymous woman who claimed to have been gang-raped for hours by drunken frat boys yet who offered not so much as a smidgen of evidence to back up her tale. Others point the finger at Sabrina Rubin Erdely, the author of this piece, who failed to execute the most basic of journalistic tasks, such as finding the alleged rapists and, err, talking to them. Some hold the editors of Rolling Stone responsible, wondering what possessed them to give the green light to such thin-gruel hackery.

There's no doubt that all these people—from the student source to the credulous journalist to the clickbait-beats-factchecking editors—have a lot of questions to answer. But we also need to cast the net wider. We need to think about the broader climate that could allow such a tall tale to appear in an esteemed publication.

We now live in an increasingly Salem-like culture, in which people are called to suspend skepticism in relation to all allegations of rape, to say "I believe" the minute anyone claims to have been raped, and to be openly and proudly credulous in response to reports of rape. This cult of credulity, this constant chanting of "I believe!" has warped the public debate about rape and sexual assault. It has now reached its nadir in the shocking suspension of skepticism at Rolling Stone in response to a fabricated horror story.

If Erdely nodded along to Jackie's story while robotically thinking "I believe," she isn't alone. Automatically and uncritically believing allegations of rape is all the rage today. Where for most of the Age of Enlightenment it was considered civilized to believe that those accused of a crime were innocent until proven guilty, now it appears the way to show that you are a good and caring person is to do pretty much the opposite. You should believe instantly the alleged victim's every word, and by extension to believe instantly that the accused is guilty as hell.

So when Dylan Farrow claimed she was sexually abused as a child by Woody Allen, the meme "I Believe Dylan" spread like a pox across the internet. #IBelieveDylan trended on Twitter. At Indiewire, Melissa Silverstein said "There are a few fundamental beliefs that I hold, and one of them is that I believe women." All women? All the time? Including, say, Condoleezza Rice when she said Saddam had loads of weapons of mass destruction? This is silly. Women are just as capable as men of making stuff up.

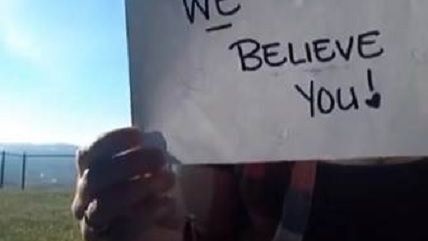

The blogger Lindy West recently set up a website called "I Believe You, It's Not Your Fault," where women share their stories of sexual assault and everyone believes them. In the United Kingdom, the website Mumsnet, where Guardian-reading moms discuss the world's problems as a Polish au pair looks after their kids, launched a rape-awareness campaign called "We Believe You."

The allegations against Bill Cosby have likewise led to outbursts of instantaneous belief, with tweeters imploring us to "Believe The Victims" (they mean accusers) and sharing memes declaring that Cosby is a rapist.

The cult of credulity doesn't apply just to women. When Shia LaBeouf rather fantastically claimed to have been raped by a woman in a crowded hipster art gallery, the cult-like chant "I believe Shia" started to spread. A writer for The Guardian, under the headline "I believe Shia LaBeouf," says she was shocked to see "expressions of doubt" on the Internet in relation to LaBeouf's claims. This is the scary situation we now find ourselves in: When it comes to rape, to doubt, to be skeptical, is apparently an act of evil. Even in relation to LaBeouf, whose last extended bit of publicity revolved around his rampant plagiarism as a filmmaker and tweeter.

There's an air of cultish religiosity to the "I believe" movement. Like theism, it is based entirely on faith. It actively discourages and even pathologizes skepticism and is suspicious of calls for evidence. It demands that everyone suspend their skepticism, reject objectivity, and simply utter the mantra: "I believe you." It demonizes objectivity. To say we should be objective about all allegations of crime, including rape, is to run the risk of being branded a "rape apologist"—as I discovered last week when I wrote a piece for USA Today saying we must presume Bill Cosby is innocent because he hasn't been proven guilty, and quickly found myself branded "pro-rape." To be skeptical is to be suspect. To demand objectivity is to be an apologist for evil.

This cult of credulity is the bastard offspring of the "Believe The Children" movement of the 1980s. Back then, in the U.S. and Europe, it was de rigueur to believe every accusation of abuse made by a child, even if a kid claimed, often under the influence of psychologists, to have been ritually abused by Satanists. To express skepticism about any of this was to be branded an enabler of abuse. As the British child-abuse expert Jean La Fontaine argued in her book Speak of the Devil: Tales of Satanic Abuse in Contemporary England (1998), the slogan "we believe the children" pathologized objectivity: "It was emphasized that if adults did not believe children, [then] they were denying help to innocent victims." And so it is today: if you don't believe Dylan Farrow or Shia LaBeouf or "Jackie," then you're heaping further pain on "innocent victims." So instead, you shoul suspend your skepticism and BELIEVE.

This is the climate in which Rolling Stone could see fit to publish an incredible tale of abuse—a climate in which credulity is worn as a badge of pride and objectivity is tantamount to a sin. Now, even as the hollowness of Jackie's claims is exposed, #IStandWithJackie is trending on Twitter and a writer for The Washington Post says we must still believe, "as a matter of default," those who make accusations of rape, because "incredulity hurts victims." It seems as if they still cannot shake their belief in Jackie's story, because theirs is effectively a religious movement, based in blind faith and openly hostile to "expressions of doubt."

The "Believe The Children" movement had a disastrous impact on Western societies. Families were ripped apart on the basis of rumors and people were unjustly jailed. The "Believe The Women" cult is also harming society. It is whipping up a climate hostile to due process and warping one of the central ideals of civilized societies: that individuals are innocent until proven guilty. And it is needlessly spreading panic on college campuses, too. In pushing an expansive new law that will further curtail due process in the name of preventing sexual assault, Sen. Kristen Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) has claimed that "women are at a greater risk of sexual assault as soon as they step onto a college campus." As Slate's Emily Yoffe has documented, this is patently false. Women between the ages of 18 and 24 who are not on college campuses are in fact 1.7 times more likely to be the victim of violent crime, including sexual assault.

When you say "I believe this woman was raped," you are saying something else, too: "I believe the suspect in question is a rapist." This turns every principle of justice on its head. The presumption of innocence has existed in some form or other for centuries, going as far back as the sixth century Byzantine Emperor Justinian the Great, who said: "Proof lies on him who asserts, not on him who denies." In short, it is the accuser we should be skeptical of, and who we should doubt, and not the responsibility of the accused to disprove the claims made against them. The cult of credulity is laying to waste this civilizing ideal, through effectively saying: "She who asserts is telling the truth; he who denies is guilty."

Yes, Jackie and Erdely and Rolling Stone have some soul-searching to do. But let's not ignore the underpinnings to this journalistic debacle—the emergence of an illiberal, intolerant, unjust climate in which all "victims" are instantly believed, even by journalists, and in which, terrifyingly, a suspect can be condemned through accusation alone.

Show Comments (277)