The Guaranteed Minimum

Much debate during the past year has centered on the Nixon Administration's plan for a guaranteed minimum income, under the Family Assistance Program proposal. To shed some light on the motivational factors involved in such assistance, Professor Semmens conducted a semester-long experiment at Arizona State University. The results are quite interesting.

As bad and as big as our welfare state is, it promises to get much worse before it gets any better. In fact, it is very likely that we shall be treated to the spectacle of a Republican Administration initiating measures of crucial significance in entrenching welfarism into our political system in much the same fashion that the Tories of Great Britain inflicted the greater part of Socialism on their country.

MAD. AVE. AD

The key turning point upon which future governmental economic and social policy may depend might very well be decided by whether we go through with the idea of the guaranteed annual income. Pressure in this direction has been building up in the past few years to the point where possibly all that's needed is the proper Madison Avenue slogan to put it over. Various partisans of this effort have tried their hands at this with such phrases as "an inalienable right to eat"[1] or by saying that such a handout would be merely the just "social wages"[2] of the poor. Even such a revered conservative economist as Milton Friedman joins the parade in reinforcing this altruistic ethic by stating that his negative income tax "is a way in which you can meet your obligations to the disadvantages."[3]

Finally, we have Melvin Laird's lament: "I wish to hell I could come up with an attractive name. 'Guaranteed income' doesn't sound good. Nor does 'negative income tax.' Figure out a good name for it and I'm halfway home."[4]

It is as if the ethics and the practicality of the plan could be easily manipulated via verbiage. Hopefully, for want of a jingle a vote will be lost, for want of a vote a bill will fail, etc. Alas though, I fear this will not be the case: sooner or later the guaranteed income will be put across and we will have to suffer the injustice and the unproductive consequences of another "great" social experiment. To give us something of a preview of these coming events, I have written of an experiment conducted on a small scale but of relevance to the question at hand: what will be the (resulting) effects of such a guarantee on the people who have to live with it?

∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗

There have been previous "experiments" in socialistic measures. History has seen the coming and going of a great many "utopian" communes and entire nations have been hard at work in the "Great Experiment" of communism. There have also been several smaller efforts along similar lines, though with a different purpose in mind. In 1951, Thomas Shelly conducted a "Lesson in Socialism" (published by the Foundation for Economic Education) in which he shared grade points in his class to demonstrate the effects of socialism to his students. In "A Small Experiment" (published in RAMPART JOURNAL, Summer 1968) I discussed another experiment along the same lines but of a more scientific nature. All of these previous examples, though, were far left in their basic theme. They were "un-moderate" in their total sharing. As such, many people are able to miss the significance of the relevance to contemporary politics. Our reforming politicians are not openly advocating complete sharing of the wealth. They only demand a "decent" minimum for all. This being the case, I contrived to set up such an experiment in moderate welfarism. The results of this venture follow.

EXPERIMENTAL SETTING

The subjects for this project were drawn from a class in a freshman political science course. They were chosen because they were available, they were interested in the project, and because the project was pertinent to their studies in the course. This method of sample selection, while frequently used because of its convenience, does present a unique situation which should be kept in mind when making generalizations and projections from the data. Namely, it should be kept in mind that the population of this country does not consist wholly or even mainly of college students. With this noted, we may proceed to the specifics of our case.

The total sample consisted of 28 students who were divided into two groups on the basis of two fundamental factors. These factors were important items which if ignored could have invalidated the entire project. First, since the lucre of our tiny welfare state was to consist of grade points, it would hardly have augered well inadvertently to place all the potential millionaires in one group. Therefore, academic performance of the previous semester was weighed and equally divided with both groups having 2.5 averages. Second, we had "level of aspiration." It would not have done to put people who would be easily satisfied in one group and all the striving and ambitious ones in the other. Individuals with comparable ability and ambition were matched, then a coin was tossed and one was placed in the experimental group and the other group. This was done for fourteen pairs of class members, thus achieving a stratified-random sample in matched groups.

GUARANTEED BEES

The medium of exchange for the project was to be grade points. Those in the experimental group were guaranteed a minimum of 25.5 points, a score sufficient for a "B." Those in the control group proceeded as is normal in college courses. The generosity of the guarantee may require some explanation. There were reasons behind this. First, I had a very small population; therefore, it was important that I offer an enticement sufficient to tempt every member of the group. This is not to be compared with offering say $15,000 as the national minimum. I feel it is comparable with an offer of $3,000 to those on the verge of earning that much. The rewards or inducements are relative, should I have had a class of "D" students, a "C" would have looked good to them. As it was, I had a class average of "C-plus" students, who could hardly be moved by a lesser reward. Second, I wanted to see what the effects would be on middle class motivations. There are some beneficial inferences to be drawn from a circumstance which can try the initiative and ethics of the middle class students. This could be some measure of response to the smug excuse that the poor can't help themselves because of their background.

The results fell into two categories; those quantitative and those qualitative.

QUANTITATIVE RESULTS

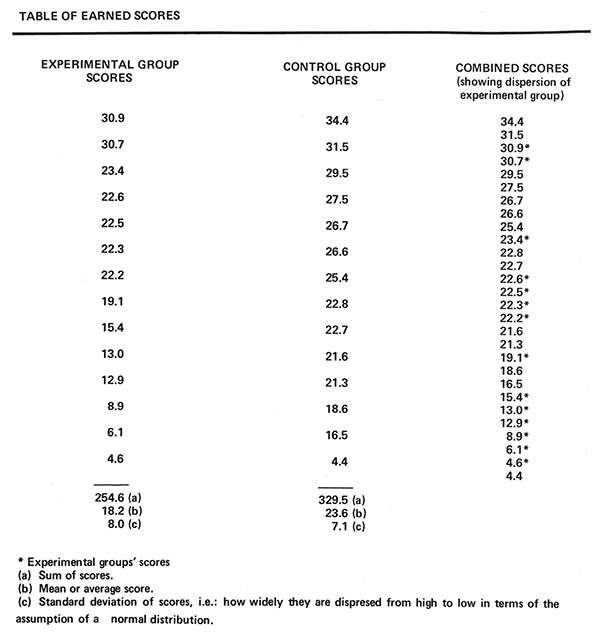

Statistically speaking, the results came out as predicted. That is, the performance of the experimental group lagged behind that of the control. Computations indicate that the difference between the two groups' means are statistically significant. [5] In terms of chance, then, this particular outcome is unlikely. We can be reasonably confident that the difference in the output in terms of grade scores was affected in some way by the experimental variable. The table below shows all of the earned points of each individual involved in the project. In the control group, where each student's grades depended solely on his own efforts, the total and average output was significantly higher. In the experimental group, output was lower with virtually the entire membership falling in the lower portion of the distribution, as can be seen in the combined list. As time went on the experimental production fell further and further behind, so that by the 15th week they were a full three weeks behind the others.

Two other measures of the motivation of each of the groups were the rate of absenteeism and the number of extra assignments turned in by each. The number of absences for the experimental group was more than double that of the control. While those subsidized with the 25.5 points had 98 absences, the control group had only 47 including seven persons with one or less classes missed, the experimental group had only two in this same category. The odds on this pattern of class attendance occurring through chance are astronomical. With regard to additional assignments, the control group handed in 13 as opposed to 6 for the experimental group.

All of this statistical data is a numerical and quantitative measure of the productivity of a number of individuals. What it all means must be a matter of interpretation. Each little scrap of information is a clue as to what is happening in a given instance. But, like all circumstantial evidence, it is not entirely conclusive. It does not explain motivation or the thoughts and feelings of those participating. To tidy up our investigation for presentation to a jury of scholars and interested parties, we ought to have some testimony from the actors. To place the figures in evidence is a fair proof, but to buttress it with personal reactions is a better one. Thus, we proceed to the next section.

QUALITATIVE RESULTS

As the term grew to a close, I put two propositions to my class. First, I asked all of them to make a written comment on their reactions to the experiment. Second, I gave all the members of the experimental group the opportunity to waive their right to the subsidy if they so desired.

The control group expressed itself as largely unaffected by the experiment. A few, goaded by the gloating of some of their friends who were in the subsidized group, voiced resentment of the policy. By and large, though, the more interesting comments came from those who were in the experimental group. All of them discussed motivation in some fashion. Half of them admitted to "slacking off" to some degree in their signed statements. It was most simply put by a student who wrote, "I believe by having a guaranteed grade, I didn't do as much work as I would have otherwise." Some of the comments became rather involved. One individual went into a lengthy rationalization of his action. He had stated upon being placed in the subsidized group that he would not accept any "free points." However, at the end of the term, he changed his mind and concluded his weighty argument by saying, "I don't feel guilty in accepting it because it wasn't my idea in the first place, and also, judging from my past performance at this college, I feel I could have earned an 'A.'" A girl in the control group rather ruefully remarked that a flip of a coin had forced her to put forth effort, but if things had been different, "I know I wouldn't have read the books or worried about writing the papers. Which means I'd have accepted something I didn't earn."

Before the experiment began, a lot of the students had placed themselves above accepting a handout. They had been "brought up right." They knew that charity was only for the disabled or those without opportunity. Yet, only three people declined to accept the guarantee. Two of them had scores over 25.5 so the guarantee was of no assistance to their grades. The sole individual who did shun the free points described a moral conflict that he had fought during the semester: "I began to be lethargic in class attendance, class work, etc. It was an enlightening experiment. The escape provided offers an ethical 'repentance' and allows me to justify my actions without compromising my beliefs."

CONCLUSIONS

The big question remaining is: How does all this relate to the real, uncontrolled, nonexperimental world? While this study was conducted in an artificial environment, I feel that it does have relevance all the same. Certainly circumstances are vastly different, but, I think, some of the basic fundamentals are the same. Most assuredly, college students are not the poor or the disadvantaged but, if a guarantee can induce some well-situated young man or woman to accept a "free grade," then is it so hard to believe that in a parallel situation, a low-incomed man might yield to a temptation just to receive a handout? A question asked of me frequently during the term was whether the subsidy was "on the level." One individual in particular was anxious on this point and, finally, when convinced it was, accepted it. The very same course of events often happens in our society. Many poor are reluctant to take welfare and have to be convinced that they should by social workers who chalk it up as a triumph when such reluctance is overcome. But what will this do to one's psyche? Few seem to be concerned and the government's pilot studies have never endeavored to ask. What will be the total effects of a national guaranteed income? The "pilot studies" have couched their reports in ambiguous terms. When such programs have been labelled successful, what does this mean? Does it mean they have gotten rid of the funds, that there have been no riots, that candidates X, Y, Z are now assured of reelection? What does the reassurance that there has not been a "flood of new applicants" mean? What is a flood? Is a "no flood" report merely a denial of an over-estimate that serves as a cover euphemism for "steadily increasing number of applicants"? One would not expect a "flood" anyway. People will need time to divert their energies from other pursuits, like jobs. The idle are already on the welfare roles, it can be safely assumed that it will take some period of time to lure others from poorly paying jobs and on to relief, to spread the word, and to break down their ethical compunctions against such a course for themselves.

It is hoped, then, that this tiny study, this small venture in investigating human motivation, can encourage some further research and some thought. Then, maybe a big mistake can be avoided.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

[1] Hazel Henderson, "The Guaranteed Minimum Income," SATURDAY REVIEW, 29 June 1968, LI, p. 16.

[2] "Flooring Poverty," COMMONWEAL, 11 October 1968, LXXXIX, pp. 45-44.

[3] "Needed: Guaranteed Income?" NEWSWEEK, 1 July 1968, LXXII, p. 29.

[4] Ibid.

[5] The statistical test used in this instance was a difference in means test with a negative direction predicted. At the .05 level with the estimated degrees of freedom at 26, we obtain a critical region on a t curve beginning with a value of -1.706. When we compute our difference in means we obtain a t score of -1.82, which falls inside of this critical zone, indicating that these results could have occurred through chance approximately 4% of the time. Therefore, in the jargon of statistical research, we can reject the null hypothesis that there is no difference between the two groups.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Guaranteed Minimum."

Show Comments (0)