The FDA's Hands-Off Approach to Medical AI Is a Win for Health-Conscious Consumers

AI-powered medical wearables and software are flourishing following the FDA’s new regulatory guidance.

Under new Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance on "low risk" wearable technology and software, AI-powered health tools are rapidly expanding, leading to major implications for cost, access, and consumer autonomy in health care.

One of the clearest examples is Doctronic, an AI-powered platform for prescription refills that rolled out in Utah this month. The FDA has not moved to regulate or stop Doctronic from operating, largely because the FDA does not regulate the actual practice of medicine. That leaves Doctronic free to innovate to patients' benefit—prescription refills with Doctronic are currently $4 and could fall as the company grows.

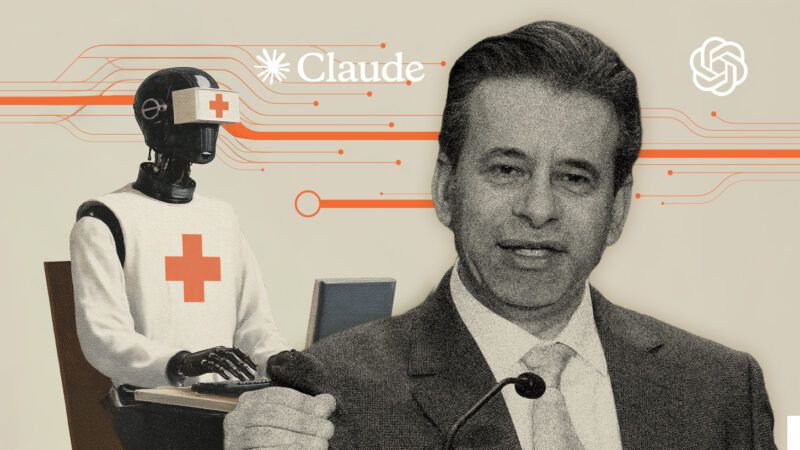

Within days of the new FDA guidance, a cascade of other innovations was announced. OpenAI unveiled a waitlist for ChatGPT Health, which offers a platform for users to connect their health data and receive insights. Anthropic, which developed the AI assistant Claude, followed with plans to improve the electronic health records ecosystem with a new product designed to meet federal patient-privacy requirements. "When connected, Claude can summarize users' medical history, explain test results in plain language, detect patterns across fitness and health metrics, and prepare questions for appointments," Anthropic announced.

Then, on January 12, OpenAI also announced its purchase of a health tech startup called Torch, which aims to address the continuity problems surrounding "fragmented" patient data. The company is developing a complement to medical record systems by unifying "lab results, medications, and visit recordings," storing patient records, and centralizing coordination.

Doctronic also announced this week that it's working on "Checkup by Doctronic," an AI-powered annual physical that includes bloodwork in addition to Doctronic's AI prescription refills. That product may be ready as soon as February 1.

These developments are possible because health wearables and software are classified by the FDA based on perceived risk and the nature of their medical claims. Tools such as Doctronic, Viome, Oura Ring, January AI, WHOOP, and Apple Watch are considered low risk rather than moderate risk because they do not diagnose disease or recommend treatment directly. Similarly, Google's MedGemma 1.5 for medical imaging for 3D CT and MRI analysis is exempt from FDA scrutiny because of its informal designation as a research and development product rather than a clinical tool.

In contrast, non-low risk software such as Natural Cycles, a software application for contraception (the first FDA-approved digital birth control) and Stelo by Dexcom, a glucose tracking monitor, are still regulated by the FDA's De Novo process for novel moderate-risk devices. Hospital-grade technologies, such as the recently announced Biotics AI fetal ultrasound, are regulated through the 510(k) process, which requires proof of equivalence to an existing device or "predicate."

The FDA's deregulatory shift is already producing benefits for innovators and consumers. WHOOP recently announced a partnership with Ferrari as its official digital health wearable. (Just six months ago, WHOOP received a warning letter from the FDA for selling an "unauthorized medical device.") But now, under the new framework, as long as a device does not claim to be "medical grade," does not diagnose disease, and remains classified as low risk, it is effectively fair game for market entry.

The FDA's move might be bigger than getting pills prescribed by an AI doctor: It could help rein in health care spending. "Medical science experts have estimated that 'widespread AI adoption within the next five years using the technology available today could result in savings of 5% to 10% of healthcare spending, or $200 to $360 billion annually'" according to Adam Thierer of the R Street Institute.

Consumers are demanding access to diagnostics without the politicization of the health environment. Users can already upload their labs to ChatGPT, for example, for analysis and second opinions. Anthropic's new tool may also be able to draft clinical trial protocols, and Oura Ring is already making clinical trials more accessible to consumers without relying on a clunky and impersonal health care system. In Utah, AI-based prescription refills are already lowering costs and returning autonomy to the health consumer.

If AI-based health software is allowed to flourish, health care costs could plummet, hospital readmission rates might drop meaningfully, and disease could be detected earlier. "Missed prevention is costly for all parties involved, including employers who insure their workforce," Rachel Curry wrote for CNBC in 2023. "The [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] says that 90% of the $4.1 trillion in annual health care expenditures are for people with chronic and mental health conditions, and preventative care is considered the key interceptor for chronic conditions."

By stepping back from strict oversight, the FDA is also saving emerging health tech companies huge amounts in layered costs. As long as AI tools don't "diagnose disease" and are simply "providing information," companies have leeway to innovate in the market without prior approval. "We don't want people changing their medicines based on a screening tool or an estimate of a physiologic parameter," FDA Commissioner Marty Makary told Fox Business.

Markets and investors want predictability, which is cited by Makary as a reason for the new FDA guidance. Rather than preemptively block innovation, the FDA is allowing competition to determine which tools succeed: "Let's let doctors choose from a competitive marketplace which ones they recommend for their patients," Makary said.

Show Comments (4)