The John Galt of Comic Books

The co-creator of Spider-Man and Dr. Strange later created some failed Ayn Rand–inspired superheroes.

Of all the popular storytelling artists striving to emulate Ayn Rand, the most significant was Steve Ditko.

Ditko, a comic book artist, is most famous for co-creating Spider-Man and Dr. Strange. Rand, in addition to writing novels that still sell hugely seven decades down the line, developed a philosophy she called Objectivism, the politics of which were highly libertarian and highly controversial.

Ditko's commitment to Rand's ideas led him down a curious and troubled path, and made him resemble a real-life Rand character. From developing enduring legends for Marvel Comics in the 1960s to Kickstartering in the 2010s with fewer than 150 sponsors his uniquely and often bizarrely abstract stories, Ditko emulated aspects of both of Rand's most prominent fictional protagonists.

Like Howard Roark, the individualist architect of The Fountainhead, Ditko insisted on doing the creative work his soul demanded, expressing his deepest self and values, even if few customers or patrons appreciated it. Like John Galt, the scientific wizard who led the strike in Atlas Shrugged, he was willing to walk away from his greatest inventions when he thought they'd fallen into hands that no longer deserved his best efforts.

Ditko's most enduring impact on comics has embedded in it a personal irony. Spider-Man, created with writer/editor Stan Lee (who milked far more public relations mileage out of his role at Marvel), is credited with pioneering the idea of a superhero with feet of clay and everyday human problems, haunted by self-doubt. Ditko was contemptuous of that perceived quality, writing that "Lee's…flawed, neurotic, anti-hero rejected the best standards for a hero as rational being at his best and as an agent of justice."

While Spider-Man was never quite as much of a sad sack teen as people sometimes remember—he was never sidelined from superheroing by acne or prom issues—he was frequently mocked and derided by his peers as teenage egghead Peter Parker. On more than one occasion, Spider-Man did blunder, by, say, trying to nab crooks he saw casing a jewelry store before they actually entered the store, so that they called the cops on him.

At times, he emitted such self-pitying declarations as "Am I really some sort of crack-pot, wasting my time seeking fame and glory? Am I more interested in the adventure of being Spider-Man than I am in helping people??…Why don't I give the whole thing up?" or "A lot of good it does me to be Spider-Man….Why don't things ever seem to turn out right for me? Why do I seem to hurt people, no matter how hard I try not to? Is this the price I must always pay for being…Spider-Man??!"

Ditko had griped about "the introduction and sanctioning of all kinds of spoilage (flaws, neurotic behavior)" into Spider-Man. He managed the tension in his mind by emphasizing that Spider-Man was still a teen, not a fully developed adult, and that the comic could show how "Parker has to learn and grow up to be a hero," as he once wrote to a fan.

One critic looking at Ditko's Spider-Man work through a Randian lens, Desmond White, wondered whether Parker's altruistic sacrifice of his time and happiness fighting crime and villains—inspired by an act of selfishness that led to the death of his beloved Uncle Ben—wasn't perhaps a slyly Objectivist experiment in showing how altruism doesn't lead to fulfillment. Despite a late-period Ditko Spider-Man villain whose moniker was the much-used Randian term "the Looter," it's difficult to squeeze Spider-Man into either an Objectivist or an anti-Objectivist mold.

Ditko's second iconic Marvel character, one even credit-hogging Lee admitted in print "twas Steve's idea," was also an ironic paladin for a Randian. The core idea of Objectivism is our ability, indeed duty, to flawlessly perceive and reason from strictly defined facts of purely material reality. Dr. Strange, a master of the mystic arts, could literally make whims come true through the speaking and casting of spells, and he spent most of his time fighting impossible, unreal beings in alternate—that is, nonexistent—dimensions.

Strange's magic peregrinations and conflicts were so bizarrely groovy, his imagery so impossibly hallucinatory, that comics editor and scholar Catherine Yronwode (who later earned Ditko's ire while writing a never-finished book about him by prying too deep into his personal life) insisted that many of the sorcerer supreme's hippie fans (a group that included Ken Kesey of the Merry Pranksters) were sure his creator must have had his soul psychedelicized.

Ditko, though, was not a man to fake reality, even within his own brain. While his adventures in a world divorced from observable, tangible reality seem un-Objectivist, one critic, Jack Elving, thought Strange was Ditko's most autobiographical character: "The hermetic sorcerer who lives in Greenwich Village surrounded by books of arcane stuff and rarely leaves his room physically, while through mental projection visiting other realms actually does resemble Ditko's lot as an artist; working in a studio surrounded by reference books and living in a world of imagination. Doctor Strange is the portrayal of Ditko's artistic life and commitment, which leaves him lonely and isolated from other people."

Those two Marvel characters, lately appearing in blockbuster movies that have grossed more than $16 billion for companies such as Disney and Sony, are far more famous than Ditko's work as an Objectivist pop artist. Seeming conflicts between those distinct parts of Ditko's career, while irresistible for critics to muse about, are best explained by the strong likelihood that Ditko's conversion to Randian thinking had not yet occurred, or at least solidified, during the 1962–1966 period when Ditko conceived, plotted, and drew those superheroes' adventures.

The Objectivist Comic Book Artist

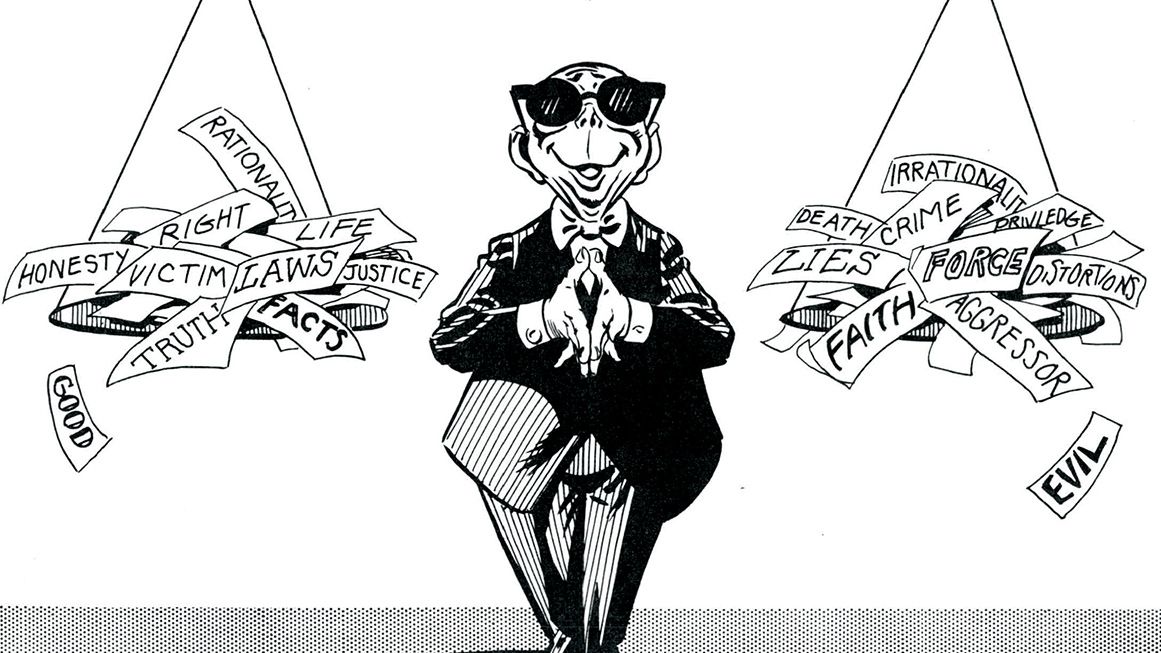

While no one seems certain when and under what circumstances Ditko became a Rand devotee—Ditko biographer Blake Bell thinks Lee may have been his entrée to her work—his unmistakably Rand-influenced art didn't start to appear until after his first departure from Marvel. In 1967, Ditko debuted a character who would never be owned by any corporation: Mr. A. The hero was named for Rand's core directive via Aristotle: that "A is A" and all reasoning must be rooted in never countenancing contradiction.

Mr. A is a vigilante with no superpowers—or perhaps, as Ditko wrote, his superpower is "knowing what's right, and acting accordingly." In a famous sequence in his first appearance, a woman stabbed by a malefactor nonetheless wants Mr. A to save the crook from falling to his death. Mr. A tells her that "to have any sympathy for a killer is an insult to their victim."

The next year, he vividly brought Rand's aesthetics into mass-market superhero stories in a Charlton Comic starring another of his creations, the Question, allied with an older superhero Ditko had significantly revamped, the Blue Beetle. The pair gets involved in a case centered on two sculptures, one representing man as misshapen and grotesque, the other strong and noble. They fight the artist and forces that want to promote the ugly, and thus anti-man, and thus anti-mind, and thus anti-life, art.

His most heavy-duty expression of superhero Randianism was in his independently published Mr. A stories. Ditko did have publishers for Mr. A, including first fellow cartoonist Wallace Wood and later Bruce Hershenson, who once said he "would never have made any money" from Mr. A as his adventures "were way too esoteric for the average person," but Ditko retained ownership of the character and work.

Ditko prided himself on being a working commercial artist, willing to take on even jobs as petty or absurd as Bob's Big Boy promos or Transformers coloring books. After all, even that was honest work, a fair exchange of value for value. But he understood that some of his more philosophical work was not for everyone, which was fine with him; it was for himself. Ditko wrote of his later work that "we are doing this primarily for ourselves and not for the purist or even for the general readers…who don't really care about issues, content."

Some of his politico-social essays were delivered with images he admitted were "a personal statement and not intended to entertain like a comic book such as Spider-Man." If perplexed readers griped that this sort of work is too complex or confusing, "their complaints are accurate. We are doing this work for our own interest, benefit, understanding, enjoyment."

Nonetheless, Ditko became convinced—not without reason, though he rarely quoted any particular evidence—that the commercial failure of nearly all his post-Marvel comics was due to fan hostility toward or incomprehension of his Objectivist-tinged ideas.

"Once I chose to become more independent (in mind/hand) in my chosen career, the negatives, the anti-Ditko, started up. I wasn't allowed to 'defect,' to be a selector of my own best interests," he wrote. Of his more Randian-coded characters, such as Mr. A and the Question, Ditko wondered: "Who did my creations…actually threaten, harm, actually DO some kind of actual abuse, harm? Who was forced to have anything to do with my published made-up characters, ideas, stories, pictures, and dialogue?" One of his one-pagers portrays a comics fan ho-humming over headlines reporting all sorts of real-world hideous crimes but going into a wild rage over a Ditko comic.

Ditko was enough of a movement Objectivist to have been a longtime funder of The Atlas Society. Jennifer Grossman, its CEO, wrote after Ditko died that the artist found the clothing in a graphic-novel adaptation of Rand's dystopian fable Anthem to be too well-made, that the shoes the comic portrayed "could only be produced by an industrial civilization."

Rand's longtime friend and biographer Barbara Branden was pretty sure that Rand wasn't personally aware of Ditko's work. But Rand did presage his importance to the spread of her philosophy by once saying something, Branden recalled, like "when Objectivism descends from the philosophers' ivory tower…to the popular culture, and finally reaches the comic books, we shall know that we are winning the battle."

Random mentions of Ditko show up now and again on some Objectivist-leaning websites, but Ditko's unique combination of pop art and Randian philosophy has been mostly as little appreciated in that world as it has been in the comics world. Chris Sciabarra, founder of The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies, who has written about Randian ideas in graphic literature, says, "I don't know of many Objectivist authors or periodicals that have dealt with Ditko."

Ditko and the Right to Comic Art

Rand's Roark was perhaps the most radical defender of artists' rights in fiction, blowing up a housing project because the builders didn't follow his original architectural plans—and convincing a jury he was right to do so with a long philosophical speech about the seminal rights of the creative mind.

Ditko had a more sophisticated set of ideas about the creator's rights in the inherently collaborative business processes that turn an artist's ideas into a finished physical product. Likely influenced by Rand's general approval bordering on veneration of the businessmen who make capitalism work, he was quick to elevate and honor the role of publishers in commercial comics. For example, because Wood was experimenting with self-publishing with his magazine Witzend and gave Ditko the space to publish the first Mr. A story, Ditko wrote that it might be fair to consider Wood as co-creator of the character.

In his dogged attempts to be true to the facts of reality and property rights in the complicated business and artistic world of comics, Ditko thought a lot about what creation and co-creation meant. Creator is a near-sacred role in Rand's world. Ditko's relationship with Lee was forever damaged over Lee generally referring to himself as the creator of various Marvel characters he wrote, ignoring the formative roles of his artist collaborators, such as Ditko and Jack Kirby.

When Ditko finally harangued Lee into writing that he "considered" Ditko to be a co-creator of Spider-Man, Lee thought it might mend fences. It did not. Because Lee said "considered," Ditko insisted he was still evading reality by not unambiguously stating that Ditko was the co-creator of Spider-Man.

His complicated moral reasoning about property rights in collaborative publications feeds into a curious fact about Ditko, one that makes him seem either highly principled or irrational. By all accounts, he never sold any of his original art pages.

Ditko controversially wrote in 1974 in the magazine Inside Comics that an original comic art page belonged most justly to the company that paid for it. "Who is the creator of the complete comic page? Who brings the page into being? The company is the first cause," he said. He also thought the existing market in original comic art was a gang of thieves selling to a gang of knaves, and he wanted nothing to do with it. But his own pages that he ended up possessing were given to him by its own choice by the publisher, who he believed justly owned them. There should have been no airtight Objectivist-rooted objection to his selling them.

This was no small matter. Long before his death in 2018, Ditko's art had become fabulously valuable, at least his 1960s Marvel pages. Ditko well might have had millions in resale value in his undistinguished office off Times Square. But there's no public evidence he ever sold any of it. One comics writer/editor who worked with Ditko, Jack C. Harris, reported in his book Working With Ditko that at least once the artist gifted him a cover. In everything I've ever read by his friends and co-workers, I've never found a reason that made sense why he should never have sold his pages. One reported that Ditko just told him, well, he doesn't need the money.

But his choices didn't need to make sense to me. He was Steve Ditko, a free individual, and his choices only had to please him.

Even when Ditko was displeased with the business decisions of people or companies he worked with, he operated from a Rand-influenced understanding about the role of business and the sacredness of trades and agreements freely entered into. He quit Marvel abruptly in 1966, and various rumors circulated for decades about why. Some historians reported that Ditko felt he deserved greater remuneration as a creator than just his page rate for his creative contributions to Spider-Man, especially after the character began raking in cash via toys and TV shows. But his own essay in 2015 about why he left Marvel does not mention that concern at all. (He credits it to Lee's refusal to speak to him anymore.) He insisted in a letter to a fan in 2015 that as far as he was concerned, "What I did with Spider-Man I was paid for."

The Heroic Artist and His Legacy

By the 1990s, Ditko was doing almost no work for big or even medium-sized comic book companies. He formed an alliance with the small-press publisher and Ditko fan Robin Snyder to publish nearly 1,000 pages of new comics over the last couple of decades of his life, as well as many essays expressing his ideas more directly than even his very didactic comics did.

The essays are nearly unreadably prolix, frequently using three words when one would do, like a man absolutely convinced the people he's talking to just don't get it. "There is a mountain of written 'truths' in scrolls, manuscripts, articles and published materials by the men believed and claimed to be wise, learned, most qualified," he wrote, "who claim to have an understanding of facts, truth, life, man, right and wrong and a knowledge of everything that is true and best for man's well-being, for human life." That's just one of many painful examples.

He still drew comics that seemed like they were trying to be narratives, still about good vs. evil, crooks betraying each other, a costumed hero simplified/reduced to being called "The Hero" foiling criminal plots in platonic fight scenes largely devoid of character or plot beyond "find crooks, beat them up," but still quivering with that curious kinetic Ditko magic, his stark shapes balleting through violence meant to show the impotence of evil in the face of a generic Good.

His sense of life largely lacked Randian benevolence. On rare occasions, he'd do a one-pager portraying people symbolically climbing a mountain to the land of successful achievement, but mostly he enjoyed portraying sputtering crooks double-crossing each other and whining complainers demanding the unearned. In the last decade of his life, Ditko drew more comics about comics fans not liking his comics than he drew about productive, happy people. His heroes defeat villains, yes, and win in that sense, but they are merely symbols, never human beings of the richness and complexity of Rand's characters. He was often, in the most insulting old-fashioned sense of the term before graphic narratives achieved cultural respectability, doing a comic book version of Rand.

Still, even some comics intellectuals who weren't devotees of Rand's ideas appreciated some of Ditko's more bludgeoningly Randian work as formally innovative. Ken Parille praised his famous work "The Avenging World" (which appeared in Reason in 1969) because Ditko "had the nerve to reject the cherished (and false) notion that comics is fundamentally a storytelling medium….['The Avenging World'] is a landmark in American comics history, an expansive work that wildly transgresses comics form: it's a non-narrative comic with embedded narrative episodes, and it moves in and out of very different modes of representational and abstract drawing styles. In comics like this and so many others, Ditko reinvented the medium."

Ditko's themes and techniques haunted later important creators of comics, including Alan Moore of Watchmen fame and Frank Miller of The Dark Knight Returns, who dragged superhero genre fiction into the light of "serious adult lit cred" in the mid-'80s while relying on Ditko's visions of vigilantism, particularly the idea that heroes had a right, perhaps even an obligation, to kill criminals. Some call that antiheroism, but Ditko's Objectivist-inspired vision told him that people forfeited their own right to life when they refused to respect others'.

Ditko's Objectivism, from outside admirers' perspective, ruined him as a popular artist, leading him to didactic hermeticism and to a more and more cranky sense of what sort of interference he could tolerate from editors whose values he did not share.

But that is not how Ditko saw it. In one of his many one-pagers about his torturous relationship with comic book fans in 2008, he drew a hideous fan tearing up a comic book and crying, "That Ditko!…Can't the *@# stop being himself…be anybody but Ditko?!?" (The aggrieved fan is labeled "the Non-A.")

Ditko's the Question answered it, with a credo by which any artist, Objectivist or not, could lay his sense of his work and its posterity: "When does a man achieve victory? When after he has honestly applied himself to the task facing him and having overcome it…is secure in the knowledge that whatever he has accomplished, the fruits of that goal belong to him! He will know…no one else matters."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Howard Roark of Comics."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"Ditko's Objectivist-inspired vision told him that people forfeited their own right to life when they refused to respect others'. [...] He will know…no one else matters."

This is the unfortunate problem that Objectivism never really addressed and the reason it will forever be an obscure philosophy largely followed by narcissistic outcasts. As a libertarian, I have seen more than a few Objectivists in my time- and seeing that Doherty appears to be one of them explains a lot about the conclusory, question begging articles he is prone to write.

The highest authority of Objectivism is the Self. You start with your premises and use logic to identify the lines of right versus wrong, and good versus evil. There is no test of what others think- no input from them. It is all your read of the facts. This is the ostensible nod to "Rational Truth". Unfortunately, because you are the judge, jury and executor of Truth, it is instead "Rationalized Truth". That is, "As long as I can rationalize doing this thing, it is moral".

The result is that you mostly see Objectivists as selfish assholes using the philosophy as a shield to justify their decisions to screw over others. Cheating on Spouses/SOs, abandoning their children, cheating others at games because the rules themselves were "immoral", emotionally manipulating friends into supporting them, then pulling the rug when the time comes for them to do the supporting.

The protagonists of Ayn Rand's laborious screeds are all perfect, unflawed men of Rationality, put up against hyperbolically immoral antagonists. And Ayn is telling people that they too can be a Prophet if they just think things through- why look at how Galt reasoned that it is wrong to steal even though all of (Rand's construed) society believes he is wrong! The common thread, however is the permission to reject others who might have already thought through what is right or wrong. If YOU can logic out a reason why doing X is okay, it doesn't matter if the entirety of society would call that a douche move- you are the authority on the matter.

Of course, we are all flawed people and sometimes we all have problems with critical thinking- especially when the questions of right or wrong come down to transactional relationships where people value things differently. Sure there are the easy calls- murder is bad. Stealing is bad. But in a world of complex relationships, the lack of an independent, unbiased authority to adjudicate matters of obligation make it too easy for a selfish person to delude themselves into thinking that they are not only authorized to shirk a commitment but MORALLY COMPELLED TO DO SO.

Many objectivists will (rightly) complain that too many other philosophies and religion instead appeal to authority. And when an authority make one bad rationalization (either through mistake or malice), it spreads across their entire movement like a plague. Wouldn't it be better for every person to rationalize what is right? No. No it wouldn't. Just as it is not better for every person to make their own food or build their own cars.

The sad part of Objectivism is that it was really onto something- encouraging people to question authority in rigorous debates starting with first principles. My personal theory is that Ayn Rand broke it when she decided she needed to justify cheating on her husband. That is when her views on morality stopped being transactional deliberations and instead personal monopolies.

In the end, Objectivism brings nothing new to the table- it is like a bunch of children in geometry class writing their own proofs and grading themselves an A because no one is allowed to correct their mistakes. Such a philosophy is great for people who simply MUST have proof that their shit don't stink, but it is a terrible way to order society.

I think youre most describing the misconstrued of objectivism. Selfishness in her books is not altering ones values to appease the values of those you disagree with. You see it in Roarke who refused yo add bells and whistles to his architectural designs because they were meaningless. He gave up a fortune following his own beliefs.

Too often rhe selfishness of Rand gets misconstrued with a type of greed. It is not. It is being first and foremost accountable to oneself.

Other libertarians like Hoppes have stated the same. The catering to others is how you get this weird leftist libertarian mix where you cater to be applauded at cocktail parties for ignoring your own belief systems. Letting those who disagree with you set the floor. How you get Reason offering up the ridiculous takes of:

Repeal ACA!!! But replace it with the exact same coverage.

Abolish government!!! Wait, we didn't mean with DOGE.

Then you have the chemjeffs of the world stating things like welfare is required because people dont donate enough by his estimation.

The funny thing about selfishness is that it does not mean to not be charitable. It just means to live up to your standards. This is best seen in her most autobiographical novel We The Living where the protagonist refused to sell her beliefs for comfort or money when given the options. And even despite giving up fortunes, the protagonist is still charitable to her family and respected friends. Same as Roarke in Fountainhead.

Randian selfishness has been consistently misconstrued for decades.

The biggest issue libertarianism has today has been the long drawn out rejection of the freedom to fail, replaced with false empathetic pleas by the left to basically kneecap libertarian theory. We must always protect and even subsidize failure. This is the biggest issue with the left libertarian alliance.

"I think youre most describing the misconstrued of objectivism. "

If it is misconstrued, it is done so by most of Objectivists, including Rand herself.

The problem with Objectivism is that it insists only self and reality are necessary to test whether your choice was truly moral or rational.

Ironically, Ayn Rand was a slave to exactly the same "Objective Value" mentality as Marx. Marx's medieval "Labor Theory of Value" suggested that a chair's value was solely determined by the inputs of materials and labor. Thus he built an entire philosophy on the notion that when one charges more than that, they are exploiting the worker and consumer. This notion is of course wrong, and was known to be wrong by people even contemporary to him who were working on the "Marginal Theory of Value".

Likewise, Ayn believes that an individual can render all moral statements to a set of objective value propositions that allow you to reason what is good versus bad. Again, when the proposition is true versus false (Will the dropped ball go down or not?), this is simple.

Unfortunately, we do not need moral codes to make physics work. We need moral philosophies to order Society- so that when we interact with each other, we are all clear on what is right versus wrong.

Social interaction is where we need clear rules, and this is where Ayn Rand fucks up epically. Because she believed that the SELF is the authority on determining the value of an obligation to another. Economics clues us in that this is not true (and since so much social interaction can be described with economics, it should be an important clue to us all). In most exchanges, your value of an item doesn't matter. The value established by the other participant doesn't matter. It is instead the price set mutually between you that matters. And this is regularly tested in reality when we see that any other attempt to change this price results in market distortions- shortages and surpluses.

Think on that- how many screeds (starting with Marx's works)- built on theory and filled with construed fictions- seem like they will work in the text, only to miserably fail in practice. The Fountainhead works because it limits so many consequences and paints Roark's antagonists just-so to make it internally consistent. But in reality Objectivism is not so tidy.

When practiced, we see Ayn Rand's philosophy fall apart. When you enter into a contract, your values and the values of your counterpart are solidified at a mutually agreed price. And many, many contracts in social interaction are implied not specified (c.f. sitting down at a restaurant and ordering a dinner). Society is full of this "Exchange of Obligations"- especially important ones like marriage. Often Objectivists (and others, to be fair) confuse a person entering into a mutual pact of obligations with being Altruistic. When I sit down at a restaurant, the server isn't giving me food altruistically- they are giving it because there is an implied obligation. Likewise, people entering into friendships, or loving relationships aren't doing so for purely altruistic reasons- they are doing so because the mutual obligation created is good for them. It is exactly a form of selfishness that Ayn Rand praised.

You could describe marriage as Altruism, or as an exchange of Obligations. Partners are trading the benefits of exclusivity for getting support from the other when they are busy. "I'll give you sex and an heir if you work while I raise the kids". "I'll focus on raising the family while you focus on career climbing". "You take care of paying the bills and I'll bring in the money." These exchanges of Obligations are built into pretty much every relationship- and they often require a wide time window- years or decades.

And this is where Rand's Objectivism fails to meet the test of society. Contrary to her theory that a bunch of people pursuing selfish interests makes society better, it in fact impedes social harmony by giving Objectivists the moral justification to renege on an exchange of obligations. They do this because they are the sole arbiter of what is valuable in a relationship- "All that time my husband supported me while I was struggling to write? That was altruism, and not valuable to me. What is valuable to me is that boy over there who gets my engine running!"

Just as socialists fail spectacularly to practice Socialism in reality, so do Objectivists fail spectacularly when they attempt to practice Objectivism in reality. They famously cannot get along together because in such a low-trust environment that Objectivists create, cooperation is either impossible or full of friction as they hedge against one another walking away from obligations.

Objectivists usually are found in paired relationships were a weaker soul is constantly shit on by a dominant person. Just as Ayn Rand cuckolded her husband and expected him to be okay with it, you find this dynamic in Objectivist relationships all around the world. An emotionally unstable person is emotionally blackmailed into believing that it is okay to be cheated on, and used for this other person's gratification only when that person wants it. In other words, such relationships only work when two people accept that one party is the sole arbiter of obligation.

Well she was an atheist after having grown up under Marxist conditions, so she didn't believe in a subjective morality thtough theology. She also didn't presuppose goodness inherent to humanity based on what she grew up under. I dont fault her for those views.

Once one assumes morality is a basis in an external source, their morality is dependent on cultural or theological development, which itself can be corrupted. So many of the values inherent in a derived morality is simply accepted truths instead of discovered truths. Which she was against. I think all of us should be as well.

I have zero problem with looking into cultural and religious morality, I have done so many times myself. But even Martin Luther sought discovered truth compared to accepted catholic.

So I wont fault rand for this as many of celebrate Protestant formation. It has always been strange to me how some people who go against accepted norms are celebrated differently, likely due to temporal distance.

"So many of the values inherent in a derived morality is simply accepted truths instead of discovered truths. Which she was against. I think all of us should be as well."

The problem with Objectivism is there is no check against the risk that your discovered truth is not true at all, but rather a rationalization of what you want.

Let me pause to say that I don't believe there is as bright a line between Accepted Truth and Discovered Truth as Objectivists imply. The number of truths we- even Objectivists- accept instead of discover are uncountable. I have not been to North Dakota, and yet I accept it is there.

Now you suggest that there is some great distinction between a a morality whose basis is in an "external source" versus a morality discovered by the Self. I don't see any great difference. Both are liable to corruption and bias. A single person is not somehow better at discovering truth than a group.

And in fact, when one finds themselves alone holding a moral value they "discovered" that does not seem to be shared by many many others, it ought to be a clue that they have not discovered a truth at all. But Objectivism doubles down here- by encouraging the person to disregard those inputs as being the result of irrationality. Again, it is almost hilarious how much Rand mirrors Marxism here. With Marx, it was about the False Consciousness- a default non sequitur used to dismiss other viewpoints. And with Objectivism it is the ultimate get out of jail free card- that as long as I can rationalize from my premise- if others disagree, it just means they are irrational.

If Objectivism were just "Think for yourself. Question the authorities," that would be fine enough. But again, as we see in practice Objectivism is much more. It is a philosophy that attracts and encourages scofflaws who are looking to shirk their obligations to one another.

The check against actual truth is to never stop looking, never treat a belief as sacrosanct.

This same issue appears under all morality schools.

I understand that is the theory, but in practice it does not work. A person who does not realize they are merely confirming their biases will not suddenly develop critical thinking skills. They will claim to be still looking for Truth, while seeking evidence to confirm what they already think to be true.

We live in a world where you can find thousands of articles confirming that YES, the world is indeed flat. If you want to confirm your biases, you will find evidence to support it.

I agree that there are similar problems on all moral philosophies. The key difference between Objectivism and those others is that the others still have a tension between the self-discovered truths and those of authorities. These include processes for testing new theories, sharing the knowledge and continuing to learn. As we have seen with Objectivism, the same is not true for Rand's philosophy. There is a reason Objectivists are largely irrelevant and relegated to obscure swinger couples and druggies. The philosophy doesn't challenge one to be better, it encourages them to rationalize what they want to do.

"I understand that is the theory, but in practice it does not work. A person who does not realize they are merely confirming their biases will not suddenly develop critical thinking skills. They will claim to be still looking for Truth, while seeking evidence to confirm what they already think to be true..."

Further, WRT to many issues, "rational ignorance" is an entirely proper response:

If someone claims Newsom is far better than a proposed D alternative, I don't care. It does not affect my beliefs regarding D politicos, nor would it affect the amount of my time spent examining those claims or my beliefs. It is simply not worth time taken from considering other matters.

Example: 2016, I voted L, believing Trump was a self-important blowhard with no chance of winning and delivering nothing. If someone asked, I'd have claimed that as a case of applied "rational ignorance".

Until he was elected and began seeing some results, even admitted by the Chron. So much for "rational ignorance" in that case.

I still believe droolin' Joe to be an imbecilic POS who should never have sat in that chair. And see no reason for further consideration.

Problem is Luigi Mangione has plenty of time to reexamine his Truth, but doing so won’t help

Human nature will forever prevent libertarianism (and it's branches) from having the society that they want.

One area where Ayn Rand was correct was the belief that libertarianism and objectivism are not the same thing.

Ayn was correct that they are not the same thing, while an complete moron in rejecting a 95% ally against a world of 0-50% enemies in deference to her ego (you might say "morals" and be an equal idiot).

NERD FIGHT!

Hahahahahahahaha! A la Far Side - Long white beards and Coke bottle glasses. Blackboards full of equations and text. Erasers flying!

Of course the sun revolves around the earth ... and other worthless statements of the ignorant.

By definition if you are not agreeing with people on Reason's comment boards, you are engaged in a nerd fight.

It always amuses me watching Reason evoke Rand yet then seemingly actually ignoring real life examples of her villains.

For example California is trying to implement a 5% tax on the wealth of all billionaires.

https://calmatters.org/health/2025/10/billionaire-tax-initiative/

Literally causing billionaires to free to Galts Gulch. But it isnt a tariff so nary a mention.

Doctor Strange was my favorite comic growing up, and the Death Merchant and the Destroyer books.

The time has come for a faithful Question movie.

You might enjoy this……

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7KiIKEKF5mw

Also, I’m a big fan of Jeffrey Combs as the voice of The Question in the Bruce Timm JLU series.

LOL!

Objectivism is just one aspect of what most libertarians believe. Philosophy is a tool to explore the rationality of the universe, not the goal itself. Even our first principles are too simplistic to survive application in the real world. One MUST have first principles, though, in order to behave morally in an imperfect world. Just as the sailor must follow the compass to have any chance of arriving at her destination, she must also change course occasionally to steer around obstructions. A rational libertarian must not allow the perfect to become the enemy of the good.

Randian Objectivism also has a potentially serious flaw. Although we should always strive to identify the reality, and not accept wishful thinking as a substitute for rationality, being CORRECT and acting CORRECTLY are not sufficient in and of themselves. For example, there is no objective reason to place the freedom of the individual at the center of the best of all possible societies. We may discover that societies based upon the inalienable rights of the individual turn out best with experience, but that depends upon our preferences for outcomes, not some fundamental discovered principle. If your preference is a world full of equally starving people with yourself in power over them, then individual rights is easily replaced by the good of all as a fundamental principle.

Astonishing number of words to convey virtually no meaning.

Ayn and Objectivism are highly aligned with libertarianism (lower case "L"), and differ mainly in philosophical fundamentals (not to be confused with conclusions) and Ayn's own ego. That Reason can't latch on to Ayn's value is their own failure. Pathetic.

Thank you for this wonderful article. I was a teenager in the Sixties, and Ditko, especially the Question and Mr. A., was my introduction to the ideas of Ayn Rand. A few years later, when I read Atlas Shrugged, it all felt very familiar to me.

I have found reprints of Ditko's Question collected in hardback with his Blue Beetle. But I don't think anyone has reprinted Mr. A.