The Cyberselfish Revival Shows Libertarianism Continues To Be Misunderstood

What's wrong with Big Tech isn't the fault of libertarianism.

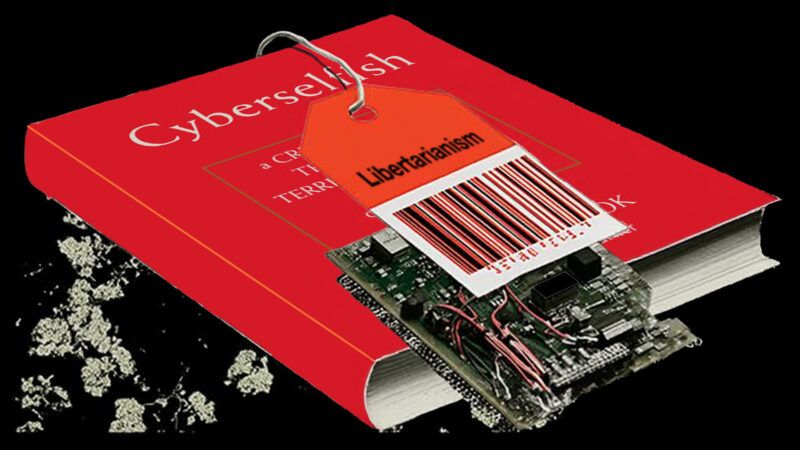

Paulina Borsook was an early writer for Wired magazine in the 1990s who became alarmed by what she saw as the encroachment of sinister libertarian ideas in the culture of a tech business world which, she correctly noted in her 2000 book Cyberselfish: A Critical Romp Through the Terribly Libertarian Culture of High-Tech, had "the big bucks, and cultural juice, that will be affecting us all as we head into the next millennium."

An unimpeachable observation in 2000, but far from a visionary or unusual one, to finger Big Tech as highly influential on America's future. The New York Times recently reported on what its journalist believes is a wide revival of interest in her ideas.

Some proof of the Times' thesis of a widespread new interest in her work is that physical used copies are unusually hard to find for a mass market book only 25 years old. Borsook recently said on the Nerd Reich podcast that this revived interest denuded the used book market for Cyberselfish. Indeed, it's not findable as such on AbeBooks or Amazon as this is written.

Cyberselfish is, though, readable for free online. Such widespread and nearly costless cultural access is one of the many (barely acknowledged by tech gripers, perhaps because of their very ubiquity) advantages for the average American of the fruits of Silicon Valley and Big Tech, if not for a writer wanting royalties.

Borsook has some arguably legitimate complaints about Big Tech of today, though in that podcast and the Times article, they are not particularly fresh or far-seeing. She worries, as the Times quotes her, that thanks to tech's cultural influence, "empathy has now become a distasteful personal failing," and "surveillance capitalism has become the default shrugged-off business practice," and "the environmental impacts of A.I. are waved away."

She also has some overarching complaints that might not seem particularly hideous to those without a natural-born leftism. She finds overly large accumulations of wealth among tech titans distasteful and potentially dangerous, and she thinks it's hypocritical of a tech world in many ways built and prospering using government-funded infrastructures to complain about it.

She said on Nerd Reich that she was offput when her natural assumption that everyone roughly shared her American liberal outlook was proven wrong in the Wired/'90s tech milieu. Cyberselfish is woven through with the mentality of someone who has a hard time grasping the intricacies, or even the basic principles and concerns, of an ideology she doesn't share.

I reviewed her book, not approvingly (though the paperback cheekily quoted me) in Reason. As I wrote in my review back in 2000:

Borsook doesn't seem to know what issues are actually the dominant concerns of libertarian writers and institutions—drug laws, education, foreign policy, and trade all go unmentioned. She has only the vaguest idea of the theoretical and empirical reasons why libertarians think what they do—not even enough to argue with them.

If Borsook were your only guide, you wouldn't think there was any economic or philosophical reasoning, any history or logic on which libertarianism is based….

Borsook doesn't understand what libertarians mean when they talk about spontaneous order. Thus she asserts that such a theory of "self-organization" appeals to "engineers' physics envy" and that "the reason for the rise in technolibertarianism is that engineers are practical and like to fix things and get things right, so of course only the sensible political choice of libertarianism would fit."

In fact, the engineering mentality, which presumes a single best way of doing things in accordance with unchanging "natural" laws, is the exact opposite of the spontaneous order mentality that pervades libertarian thinking. That's why Hayek specifically identified the engineering mentality as the mind-set from "which all modern socialism, planning and totalitarianism derives."…

The libertarian insight that the state is the nexus of legalized violence and coercion—and awareness of the special moral and practical dilemmas that its use thus involves—escapes Borsook entirely; she never even mentions it to try to refute it. Ignorant of the philosophical and intellectual background behind small-state thinking, she condemns it for being against cooperation. In fact, libertarians rely on uncoerced transactions and charitable fellow-feeling as the web holding civil society together—cooperation on mutually agreed terms at its finest, without force entering the equation.

The biggest intellectual problem with her book, and with those waving her notions as a flag against tech today, is that neither she nor they can sensibly root their complaints about the tech industry in a supposed dominance of libertarian thinking in that world. Indeed, the Nerd Reich podcast openly frames the complaints about Big Tech that both the host and Borsook share as about "tech fascism." That's far closer to their point than to blame their critiques on libertarianism.

Nearly all her complaints (except those rooted in the notion that embracing libertarian ideas just makes you an unpleasant and bad person, which was a large part of the message of Cyberselfish) have almost nothing to do with libertarianism or the dominance of the same in the world of tech.

Yes, the wave of love and support that President Donald Trump has received from dominant figures in the tech industry is alarming and unsavory, especially given his violent hostility toward trade and immigration, both important to tech as an international business. The technosurveillance state is alarming and sinister when it involves providing such services of information processing and gathering to government, which can use it for oppressive and evil purposes. (When it comes to all the information we willingly provide to social networks and other websites and how tech companies can use them to form dossiers of physical and intellectual tracking, that's mostly a choice we've made in return for all the many free-to-the-user services we get, however much we might wish we didn't have to make that choice.)

To the extent Big Tech has dinged our culture, it's largely a result of choices that We the People have made about how to use their services, nothing they have forced us into. (Yes, the algorithms many sites use to shape what they show us complicate this analysis, but fine-grained observation about the tradeoffs on how tech impacts users lives isn't what Borsook is selling.)

Borsook was somewhat prescient, though not unique, in being annoyed by Big Tech and the personalities of its leading figures a couple of decades before even more people project that annoyance. But she and her devotees are mostly driven by a vague sense of the failures or distastefulness of any anti-government thought. The host of Nerd Reich makes a point in commiserating with Borsook based on the idea that Proposition 13's property tax limitations are somehow to blame for making modern California significantly worse by starving government, not noting that since its passage, state government spending has increased well more than 4x (in inflation-adjusted terms) while its population has not quite doubled.

Borsook does in that podcast make one thoughtful point that connects libertarian thinking with modern tech mogul behavior, which is more than she did in all of Cyberselfish: that their pathetic kowtowing to Trump might well be no reflection of any actual affection for him or his policies, but rather hewing to Milton Friedman's theory that a corporation's greatest responsibility is to prop up shareholder value, which might understandably be harmed by displeasing our angry and vindictive chief executive.

Despite the pretensions in the Times piece that she made groundbreaking discoveries or arguments, at the time, the book seemed just an early book-length summation of a set of complaints about libertarianism that were quite widespread and applied to an area of business culture whose associations with libertarianism were widely understood. (See, for example, John Perry Barlow, who Borsook makes fun of in the Nerd Reich podcast and his "Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace," and the fact that founding Wired editor Louis Rossetto wrote a positive cover story in 1971 for the New York Times Sunday Magazine about libertarianism.)

Certainly seeing in 2000 that tech business culture was going to reshape the world in a huge way was obvious, not particularly farseeing. Her book then was not particularly groundbreaking in its context (even if she could rightfully note that other tech-doubters such as David Golombia have definitely trod in her path), just summational of a widespread anti-libertarian mindset, often rooted in ignorant confusion about what libertarianism even was or advocated. A Borsook revival, if it has legs, shows that hostile ignorance about libertarianism is still widespread now.

Show Comments (11)