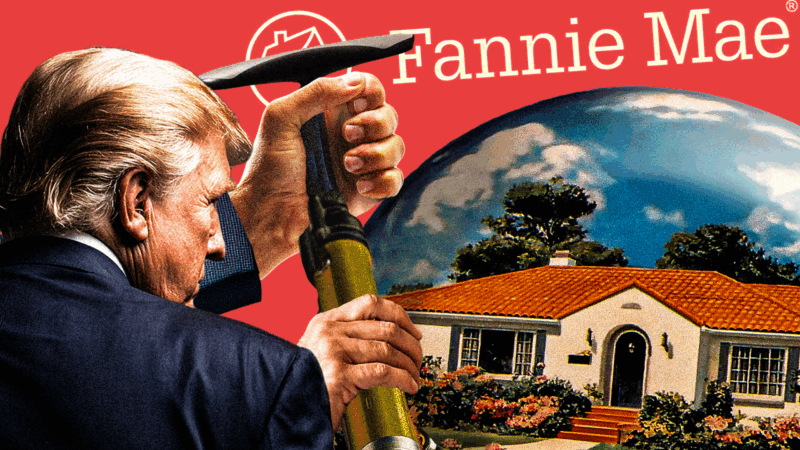

The Trump Administration's Latest Housing 'Fix' Could Inflate Another Bubble

Socializing risk to subsidize demand isn't a solution to the housing crisis, but it is a good start to another financial crisis.

President Donald Trump made headlines with his controversial proposal to make housing affordable by introducing 50-year mortgages. While that plan was merely floated—and may not even be legal—the administration has laid the groundwork for another housing bubble by eliminating the minimum FICO score requirement for federally-backed home loans.

Last Wednesday, Fannie Mae announced that "the minimum representative credit score requirement of 620…will be removed for new loan casefiles created on or after Nov. 16." Fannie Mae, a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE), doesn't lend to borrowers directly, but purchases mortgage loans from private lenders like commercial banks. Together with Freddie Mac, another GSE that buys mortgages, the two "support around 70 percent of the U.S. mortgage market," according to The New York Times.

Instead of relying on this minimum FICO score, Desktop Underwriter, Fannie Mae's automated mortgage loan underwriting system that helps lenders determine whether a loan is eligible for purchase by Fannie Mae, will "rely on its own comprehensive analysis of risk factors to determine eligibility." Despite the change, Bill Pulte, director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) that oversees Fannie Mae, insisted that Fannie Mae's "underwriting standards are the same."

Pulte simultaneously pitched the plan as a "big deal for consumers." On this point, he's not wrong—the policy is eerily reminiscent of those that precipitated the 2008 financial crisis; it socializes the risk and incentivizes lenders to issue loans to those who are more likely to default. Anthony Randazzo, former senior fellow at the Reason Foundation (the think tank that publishes this magazine), explains that, leading up to the Great Recession, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac "decided to begin taking on riskier mortgages in order to grab a slice of the subprime mortgage market [because] they knew they had a government safety net to back them up." Adding insult to injury, the Securities and Exchange Commission charged top executives of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac with securities fraud for misleading investors about their subprime exposure.

Peter Wallison, senior fellow emeritus at the American Enterprise Institute, explained to Reason that, of the "28 million subprime or very weak mortgages [in 2008]….20.4 million were on the books of government agencies like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac…that were holding them as a requirement of the Community Reinvestment Act." When subprime borrowers defaulted, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had their losses socialized: Both were put under FHFA conservatorship and bailed out by taxpayers to the tune of $189 billion.

Despite instigating the Great Recession, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac still have a huge hand in American homeownership via the secondary mortgage market. Fannie Mae guaranteed 25 percent of single-family residential mortgage debt in June and provided $287 billion in liquidity to the mortgage market in the first nine months of 2025, per its September fact sheet.

Jessica Riedl, senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, fears that eliminating the minimum credit requirement "may end up as a political move to expand homeownership without regard to whether the families can afford the loans." David Bahnsen, managing partner at the Bahnsen Group, a wealth management firm, is not so concerned. He tells Reason that, while it is "marginally possible" that the elimination of the minimum credit score may subsidize demand for unqualified homebuyers, "income verification is now so rigorous [that he doesn't] see much room for expanding credit worthiness to really expand affordability." He says that "income verification and appropriate debt-to-income ratios are the most important metric" in determining creditworthiness.

It's still early to tell what the exact impact of this policy change will be, but as history shows, providing federally-backed mortgages to those with dubious credit histories isn't a fix to the housing crisis. Rather than boosting the supply of housing, this plan could socialize risk and potentially inflate prices.

Show Comments (32)