This Year's Nobel Winners for Economics Explained How Innovation Makes Us Rich

Joel Mokyr has long made the case against technophobia, including in the pages of Reason.

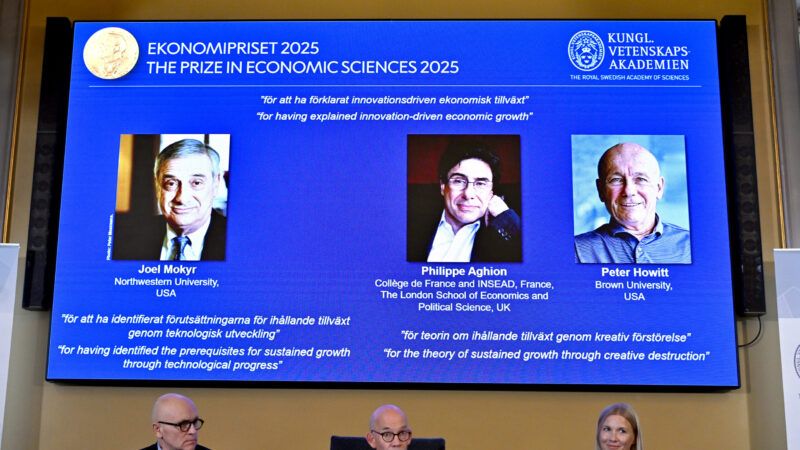

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences on Monday awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences to Northwestern University professor and Reason contributor Joel Mokyr "for having identified the prerequisites for sustained growth through technological progress." He shares the prize with Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, who won the other half jointly "for the theory of sustained growth through creative destruction."

Together, the trio had explained how innovation drives economic growth, the academy said, when economic stagnation had been the rule, as opposed to the exception, for the vast majority of human history. As a result of that upswing, countless people have been lifted out of poverty.

For his part, Mokyr's work has focused on the intersection of economics, culture, and history, emphasizing both the importance of understanding why various technologies work if they are to successfully build on each other, as well the affluence that comes from openness to new ideas. In reviewing Mokyr's 2016 book, A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy, the classical liberal economist Deirdre McCloskey wrote that Mokyr "is a Nobel-worthy economic scientist, right down to his wingtip shoes."

At the announcement Monday for the pro-growth winners, the prize committee issued a warning against anti-growth policies, like tariffs and restrictive immigration. That the road to economic stagnation is multifaceted is something Mokyr knows well, as he outlined several times in Reason throughout the 1990s, directing his focus to certain topics in a way that would seem prescient in retrospect, and which still help elucidate problems society faces today.

"The most persuasive case against protectionism is not the standard one that undergraduate students are taught in their introductions to international economics, which goes like this: Tariffs distort the allocation of resources and impose a 'deadweight burden,'" Mokyr wrote in the June 1996 issue of Reason. "The standard argument is certainly correct, but somehow it has failed to persuade many people since it was first enunciated by Adam Smith and David Ricardo."

The better argument, instead, is that "protectionism and insularism impede innovation, depriving our children of the comfort and security that progress and economic growth bring," he said. "Free trade and international competition not only lead to a better allocation of resources; they ensure that countries do not lull themselves into the technological lethargy that is the archenemy of economic growth."

So, too, has Mokyr long understood the anxiety around technological progress, often portrayed as a form of regression. "What explains technophobia?" he asked in the January 1996 issue of Reason. He noted that while technology pessimists were "neither insane nor ignorant," their objections were "misguided and futile," like nostalgia, risk aversion, and social costs like pollution. Sound familiar?

Across Mokyr's Reason pieces (others can be found here and here)—and his work broadly—is the belief that innovation is good, actually. It's a message that has long received pushback from some of the louder voices in the room, despite it fundamentally being one of optimism and progress.

"As long as they insist, with fellow-traveler Wendell Berry, that a new contraption should be adopted only if it is cheaper, smaller, and locally made; uses less energy; does not disrupt anything good that already exists (including family and community relationships); does not infringe on the rights of other species (plants and animals alike); and does not harm the interests of the next seven generations," he wrote in that January 1996 essay, "the 'neo-Luddite' movement will inspire derision rather than effective technological resistance."

Show Comments (21)