Reality Winner Got 5 Years in Federal Prison for Leaking 5-Page Document

In her memoir, the former NSA contractor details her journey from top secret security clearance to federal prison.

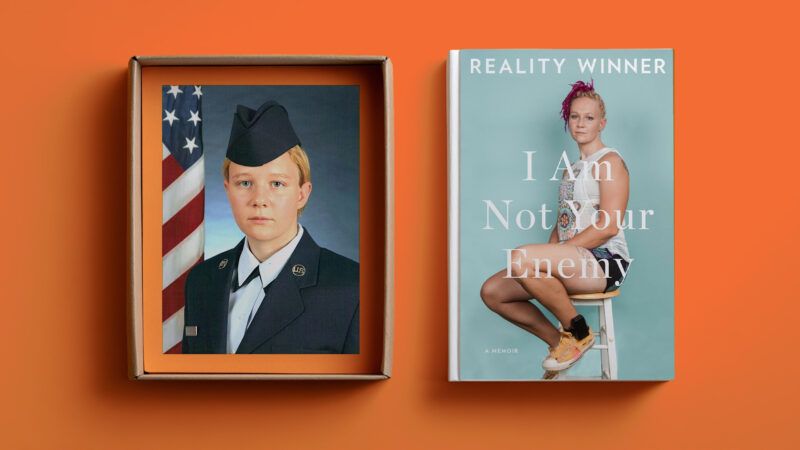

I Am Not Your Enemy, by Reality Winner, Spiegel & Grau, 336 pages, $30

During World War I, the Committee on Public Information—a short-lived agency Smithsonian Magazine would describe in retrospect as "Woodrow Wilson's propaganda machine"—ran an advertisement titled "Spies and Lies."

"German agents are everywhere, eager to gather scraps of news about our men, our ships, our munitions," the ad warned. "But while the enemy is most industrious in trying to collect information…he is not superhuman—indeed he is often very stupid, and would fail to get what he wants were it not deliberately handed to him by the carelessness of loyal Americans." It not only warned Americans against discussing facts (or rumors) about the war effort, but advised them to report anyone who even "spreads pessimistic stories" or "belittles our efforts to win the war."

During World War II, government-sponsored propaganda posters carried the slogan "Loose Lips Might Sink Ships." (The U.K. went with the stuffier "Careless Talk Costs Lives.") The message was the same: Even if you didn't relay info about the war effort directly to a foreign government, you may still be helping it get there.

More than a century after "Spies and Lies," that remains the sentiment in Washington. Presidential administrations increasingly treat leaks to the press like espionage, branding leakers as traitors and threatening them with decades in prison under statutes designed to go after foreign agents.

In 2017, an Air Force veteran and National Security Agency (NSA) contractor improbably named Reality Winner became one of the leakers prosecuted under one of those statutes. After mailing The Intercept a report on Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, Winner was arrested and held without bond; FBI agents accused her in court of sympathizing with the Taliban. After she pleaded guilty, she received the longest civilian sentence in American history for leaking to the press.

In her new memoir, I Am Not Your Enemy, Winner tries to account for why she did what she did, though even she apparently struggles to understand. "The truth is, I don't know," she writes. "A blank spot exists where my precise motivations should be."

Winner reads as intelligent yet impulsive, and quite a bit immature. What shows through most prominently is a tale of a patriot, raised to revere the military, whose very involvement with the government leads her to despise and distrust it.

Winner writes drily and bluntly, injecting irony into even some of her bleaker passages. "If you have never been arrested by the FBI and thrown in jail on an espionage charge at the age of twenty-five, I advise against it," she writes. "Zero out of ten would not recommend. Consider this a zero-star review."

As she grew up in south Texas, her mother was unfailingly supportive; her father was abusive but also sparked her intellectual curiosity. It was her dad who named her Reality—a variation on a T-shirt slogan he liked, about being a "real winner."

"When I consider my odds for having an ordinary life, given my childhood," she writes, "the first image that pops into my head is my draft-dodging, drug-dealing, opioid-addicted father, who named me after a T-shirt."

Leakers are often viewed through ideological prisms. Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked a top-secret report about U.S. involvement in Vietnam, became an anti-war activist; Edward Snowden, who leaked information about NSA spying programs, donated to Ron Paul's 2012 presidential campaign.

And Winner? She writes that Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign "revolted" her, and she describes his first press briefing in January 2017 as "the starting whistle in a race to fascism." Among her friends, she regularly inveighs against issues like climate change, racism, and factory farming—becoming, she admits, "unbearable to be around." But she's not exactly a loyal Democrat. "I spent my free time protesting Democratic presidents, not worshipping them," she writes. "If Hillary Clinton had won the 2016 presidential election, I don't think she would have been a good president. She was far too enthralled with the goodness of US power, having campaigned for the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya." She takes shots at "people on the left" who fail to appreciate that a "vegetarian do-gooder" like her could own guns and "be simultaneously pro-military and pro-humanitarianism."

As a pre-teen, after 9/11, Winner became obsessed with the concept of Islamist terrorism; she went to the public library, desperate to find any information to explain why some people hated the U.S. so much that they chose to die flying airplanes into office buildings. Hoping to grasp the full picture, she started learning Arabic, in addition to her high school Latin classes. (Years later, a federal judge would cite her "fascination with the Middle East and Islamic terrorism" to say she posed a flight risk and should be denied bail.) Nearing high school graduation, she saw the armed forces as a way to make the world a better place while satisfying her burgeoning interest in languages. In 2010, as her classmates went off to college, Winner joined the U.S. Air Force to become a linguist.

The U.S. was in the middle of what would become a two-decade war in Afghanistan. Winner hoped to learn Pashto, a language spoken in Afghanistan and parts of Pakistan. When the Air Force instead assigned her Farsi, the primary language of Iran, she decided to learn Pashto in her free time while also learning Farsi in class. With her training complete, she worked jointly for the Air Force and the NSA, translating radio communications in the Middle East.

She quickly became disillusioned. Becoming a linguist, she had been told, would mean "learning the language to understand the cultures of foreign lands, since only by understanding the cultures could America succeed in its efforts at state building and peace building." Instead, she was translating conversations to see which spots to bomb. The Air Force gave her an award for her work helping to kill, capture, or identify hundreds of targets, but "being good at identifying large numbers of people to kill didn't make me feel proud."

When her enlistment ended, she hoped to join a nonprofit, deploy overseas, and help build schools or dig wells. But with no college degree and a résumé that was mostly classified, Winner's job prospects were slim. She took a job with an NSA contractor doing work similar to what she had done before. She started in the position in early 2017, soon after Trump was sworn in as president.

At the time, a lot of public commentary revolved around allegations of Russian interference in the election. Hackers apparently affiliated with the Kremlin had used phishing attacks to access the email accounts of the Democratic National Committee and Hillary Clinton campaign chair John Podesta, the contents of which were then leaked.

"Russia's goals were to undermine public faith in the US democratic process, denigrate Secretary Clinton, and harm her electability and potential presidency," a January 2017 intelligence community report declared. "We further assess [Russian President Vladimir] Putin and the Russian Government developed a clear preference for President-elect Trump." This was embarrassing, but not much worse than that: As the report noted, of everything the hackers went after, "the types of systems we observed Russian actors targeting or compromising are not involved in vote tallying."

At her new posting, Winner saw a report in the NSA's internal portal about attacks on U.S. election infrastructure. It suggested Russia's intelligence services "executed cyber espionage operations" against an American company "in August 2016, evidently to obtain information on elections-related software and hardware solutions," which could then be used to spoof email accounts and gain access to "U.S. local government organizations."

The report didn't suggest hackers changed votes or voter information, or even that they gained access. Still, it would be news to the public, and it contradicted what the intelligence community was saying publicly. "It was, I believed, crucial information that could further illuminate the accumulating understanding of the president's ties to Russia," Winner writes.

At the time, Trump made no secret of his disdain for the FBI's investigations of Russian interference, including the allegations that the president was somehow involved. On May 9, 2017, he fired the FBI director—over "this Russia thing," he later admitted. The very same day, Winner printed out the report. She later folded it up, smuggled it out of the building, and mailed it to The Intercept, which was known as a place for whistleblowers to leak classified information. Winner thought its staff would know how to handle the document. She would quickly be proven wrong.

When the report hit The Intercept's mailbox, a reporter contacted a source in the intelligence community to verify its authenticity. In the process, he revealed it had been postmarked in Fort Gordon, Georgia—home to the NSA location where Winner worked. The Intercept also later gave the agency a copy of the document for verification, which the FBI used to narrow down the leaker's identity. "The [NSA] examined the document…and determined the pages of the intelligence reporting appeared to be folded and/or creased, suggesting they had been printed and hand-carried out of a secured space," according to an FBI agent's affidavit. From there, it was easy to track down who in Fort Gordon had printed it out.

Not all of this was The Intercept's fault; Winner was also quite sloppy. According to the FBI affidavit, the NSA "conducted an internal audit" and determined that six people had printed out the report in question. Of those six, they found Winner had emailed The Intercept from her work computer, inquiring about a podcast transcript.

The FBI showed up at Winner's door just 48 hours after The Intercept submitted the report for authentication. She was blindsided, but the agent framed the visit less as an interrogation than a "conversation"—never advising her of her Miranda rights—so she spoke without asking for a lawyer. "Believing in the value of speaking with agents of the state might seem naive," Winner writes. "But, well, I am a naive person at times." Within hours, she was in handcuffs, en route to the county jail. The Intercept published the article based on her leak two days later, an hour before she was indicted.

If anything, Winner undersells her naivete. The full transcript of her interrogation is available online; playwright Tina Satter adapted it—verbatim—into the Broadway production Is This a Room, and then into the HBO film Reality. "She seems like a teenager," New York Times theater critic Jesse Green wrote in his review of the play. ("The truth was not far off," Winner acknowledges.) Even after she was arrested and booked into prison, she made incriminating statements on (recorded) jailhouse phone calls. Prosecutors played them in court, often out of context.

Investigators scoured her private journals, interpreting lists of places she wanted to travel as plans to flee extradition, and taking her notes about Taliban leaders as a desire to join their cause. Her interest in Middle Eastern languages, part of a Pollyannaish quest to make the world a better place, became proof of a secret goal to become an anti-American Islamist. (By then, Winner notes, she had converted to Judaism, which would win her no friends among the Taliban.)

This story paints an unflattering portrait of an impulsive, unsavvy operator. When Edward Snowden leaked NSA files to journalists, he did so after many months of meticulous planning, encrypted communications, and a flight halfway around the world. "By contrast," Winner writes, "I spontaneously tapped the print button on a five-page document involving intelligence from the previous year without giving the whole thing much thought."

It all suggests she was not some hardened America-hating spy, but a young woman who did something foolish for what she felt was a good reason. "Excessive concealment is wrong even if it doesn't undermine trust," she writes. "It's wrong because the public has a right to know what the government does on its behalf. The bias should be toward making all information available to everyone, not just those in the national security state. That's called democracy."

Winner's was not the biggest leak of classified information, nor the most consequential. Snowden handed over at least 60 gigabytes of data, totaling around 1.7 million documents. In 2010, Chelsea Manning released 1.73 gigabytes of data to WikiLeaks, totaling 750,000 documents and videos. At the time, Manning's release eclipsed the previous record holder, Daniel Ellsberg's leak of the 7,000-page Pentagon Papers—though in Ellsberg's defense, he had to photocopy the entire report.

By contrast, Winner's leak of a single report ran just five pages in length. Unlike those earlier leaks, this one seemed to make little difference to the public. Today, even casual news consumers are at least vaguely familiar with most major national security leaks: Snowden showed that the NSA is spying on us, Ellsberg that the government lied about the Vietnam War. Winner's leak made little impact on the news cycle past the story of the leaker herself, the blonde linguist with the wacky name.

And yet like many other leakers in recent years, Winner was charged under the Espionage Act, a law passed during World War I that criminalizes sharing any information that could hinder American national security. For decades, it was used sparingly, typically for spies such as Aldrich Ames or Robert Hanssen. But under President Barack Obama, the government prosecuted six people under the Espionage Act for releasing classified information to the press—more than all previous presidents combined.

Winner was the first Espionage Act prosecution under Trump, but not the last. Under President Joe Biden, the government indicted several more—including Trump himself, for keeping classified documents after he left office.

"Although that law was intended to catch spies who give information to enemy governments, it does not have any exceptions for whistleblowing or divulging information in the public interest," Reason's Scott Shackford wrote in 2018. Though Winner believed the information was in the public interest, she could not say so if the case went to trial.

The government can also play favorites with those it prosecutes, and for what. As Winner bitterly notes throughout the book, leaks are a fact of life in Washington, and relatively few are charged for it, because much of the information is leaked by the government itself for political purposes.

Snowden had "only done in the macro what the national security establishment does in the micro every day of the week to manage, manipulate and influence ongoing policy debates," Jack Schafer wrote in 2013. "Secrets are sacrosanct in Washington until officials find political expediency in either declassifying them or leaking them selectively."

"Even as presidents complain bitterly about leaks and vilify leakers, the fact is that in all recent administrations, White House aides and cabinet officials have consistently engaged in rampant leaking themselves," Gabriel Schoenfeld noted in 2014.

Winner is aware of the double standard. "Donald Trump, Joe Biden, Hillary Clinton, and Mike Pence all mishandled scores of classified materials. Trump had thirty-three fucking boxes of stuff that he was not entitled to…and shared it with anyone he felt like impressing," she writes. David Petraeus—who had served as both CIA director and commander of military operations in the Middle East—"shared entire notebooks' worth of classified information" with his biographer while they engaged in an extramarital affair. According to a federal indictment, this included "the identities of covert officers, war strategy, intelligence capabilities and mechanisms," and notes from National Security Council meetings. But Petraeus received only probation and a $200,000 fine (all while receiving a $208,000 army pension).

Winner pleaded guilty to a single felony count, and in 2018, a federal judge sentenced her to five years and three months in prison. U.S. Attorney Bobby L. Christine bragged that the sentence was "the longest received by a defendant for an unauthorized disclosure of national defense information to the media."

In prison, Winner writes, she lived alongside killers and women with severe mental health problems—and yet she consistently found them less of a threat to safety and order than her jailers. She writes of complete strangers who went out of their way to help her, offering advice or sharing rationed amenities. When two inmates have a conflict, others step in to mediate. On the other hand, after COVID-19 lockdowns put an end to yard time, a guard threatened Winner with solitary confinement for doing push-ups in her cell.

"When you are incarcerated and the majority of abuse comes not from the criminals around you but from the uniforms of the government, you understand how to build a real community of mutual respect and trust that can transcend most individual disputes," Winner writes.

In 2021, Winner secured early release for good behavior. Once she dreamed of traveling the world and helping heal schisms between warring peoples; now she runs a CrossFit gym in her hometown.

"I helped the United States government kill people," she writes. "I was good at it. So good that they gave me an award for it. But then I shared some information with the American people, and the US government felt that was a much worse thing to do than killing scores of people."

Show Comments (44)