College Students Across the Political Spectrum Support Shouting Down Opponents

Once a left-wing fetish, the heckler’s veto has gained conservative adherents.

It's a given that if one party to a disagreement keeps breaking the rules in order to harm opponents, the other participants will eventually sink to the challenge and adopt—or escalate—out-of-bounds tactics themselves. That's bad enough in any conflict, but it can be disastrous for a free and open society if the rules being broken by all parties are fundamental free speech norms. For years, we've seen left-leaning students and faculty on college campuses shout down and sometimes assault speakers with whom they disagree. Now right-leaning students have joined the party, embracing the heckler's veto and even the use of violence to muzzle dissent.

You are reading The Rattler from J.D. Tuccille and Reason. Get more of J.D.'s commentary on government overreach and threats to everyday liberty.

Shouting Down Opponents

In March, an event including former Israeli foreign minister Tzipi Livni "descended into chaos when unruly activists broke out in antisemitic chants and hurled abuse at the politician," according to the New York Post. Cornell University President Michael Kotlikoff denounced the interruption and 13 protesters were arrested for disorderly conduct with four others referred for disciplinary proceedings.

That was a better official reaction than when Judge Kyle Duncan of the U.S. Court of Appeals was shouted down at Stanford Law School and an administrator asked to calm the situation instead joined the denunciations of the invited speaker.

Worse was a 2017 incident when political writer Charles Murray's scheduled lecture at Middlebury College was drowned out by protesters who then escalated to shoving, pulling hair, and jumping on vehicles.

"We were confronted by a mob that man-handled us that — had it not been for the security guards — at the very least, I would have been on the ground," Murray told Time.

Middlebury Professor Allison Stanger, who accompanied Murray, was treated for a neck injury and concussion suffered in the attack. She blamed her colleagues for instigating violence.

The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) maintains a database of efforts to silence speakers, most of them far less dramatic in nature. The majority over the years have come from the left, but not exclusively so. FIRE now suggests that enthusiasm for the heckler's veto is growing on the right.

Republicans Adopt the Left's Taste for Muzzling Dissent

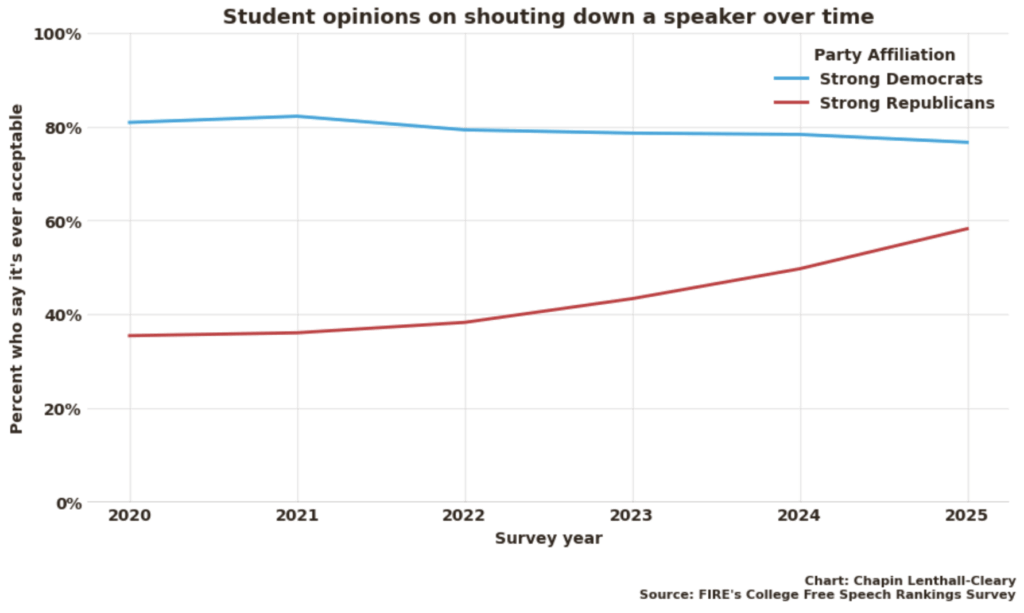

"Until recently, these vices primarily belonged to Democratic students, with a staggering 79% of students who identify as strong Democrats agreeing that shouting down a speaker is at least rarely acceptable," Chapin Lenthall-Cleary wrote last week for the organization. "Republicans have finally, perhaps belatedly, arrived at the party, with over half of strong Republicans now saying it's acceptable to shout down a speaker."

Lenthall-Cleary works from the latest College Free Speech Rankings Survey. The survey asked respondents how acceptable they think it is for students to shout down a speaker, block other students from attending a speech, or use violence to prevent a campus speech. As of 2020, just over 80 percent of students who identified themselves as strong Democrats said these tactics are at least rarely acceptable. Fewer than 40 percent of strong Republican students agreed. But over the years since then, the number of Democratic students holding that opinion has inched down just a bit while Republican support has climbed close to 60 percent.

Endorsement of Violence

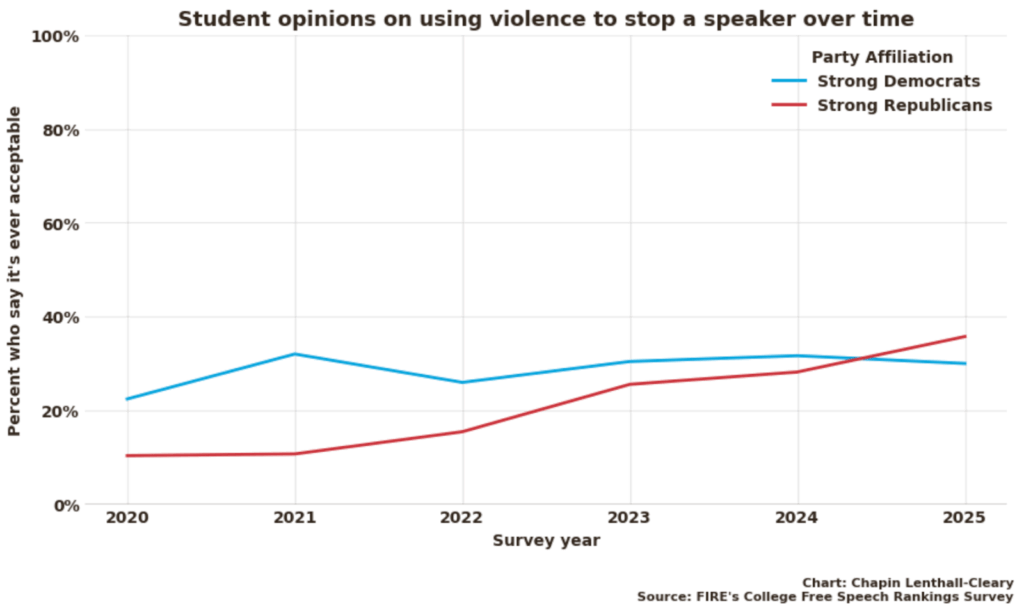

And those Republican students willing to muzzle the opposition are ready to embrace severe tactics. "In 2025, strong Republicans passed strong Democrats in support for using violence to shout down a speaker," according to Lenthall-Cleary. In neither case does a majority embrace violence, but somewhere around 30 percent of strong Democrat students are willing to consider it, compared to perhaps 35 percent of strong Republicans.

As Lenthall-Cleary puts it, "Republican students are still overall less interested in disruption, but when they are interested, they're really interested."

It's not hard to guess why opinions have shifted on this issue. If you've seen your events disrupted and your speakers drowned out and roughed up for years by people who insist that such tactics are perfectly acceptable, it's inevitable that you'll finally take them at their word. If shouting down anybody who disagrees with one side is fine and dandy, then it must be equally acceptable if other groups return the favor. And so, taking on an engagement at a college campus threatens to become an exercise in frustration if not a contact sport, no matter whose views are represented.

That sets the stage for an interesting dynamic as we enter a new academic year with campus protests over Gaza, immigration, and national politics guaranteed. Students, faculty, administrators, and the federal government are all navigating what rules apply now that the old norms have broken down and nobody seems to know where the boundaries are in terms of expressing yourself—or allowing opponents to speak.

We Could Return to Tolerance for Opposing Views

A good place to start is a revival of the liberal truce that once allowed everybody to speak and to rebut each other with more speech. The Chicago Principles, developed at the University of Chicago and adopted elsewhere, are a time-tested alternative to the developing no-holds-barred free-for-all.

"The University's fundamental commitment is to the principle that debate or deliberation may not be suppressed because the ideas put forth are thought by some or even by most members of the University community to be offensive, unwise, immoral, or wrong-headed," the principles state, in part. "As a corollary to the University's commitment to protect and promote free expression, members of the University community must also act in conformity with the principle of free expression. Although members of the University community are free to criticize and contest the views expressed on campus, and to criticize and contest speakers who are invited to express their views on campus, they may not obstruct or otherwise interfere with the freedom of others to express views they reject or even loathe."

Universities—and the rest of the country—can't just passively point to these ideas either. The idea that you wait your turn to speak and then express your disagreement must be based on expectations of civility and enforcement of the same. If you can't stay quiet when it's somebody else's turn, or refrain from throwing punches over disagreement, that needs to carry consequences.

Or we could just see who can shout the loudest and hit the hardest. Those are always convincing arguments—if only to those who make them.

Show Comments (68)