Zombie Knives Don't Kill People, but Banning Them Kills Liberty

Britain’s crackdown on “zombie-style” knives shows how politicians blame objects instead of criminals—and how bans only hurt the law-abiding.

In July, 25-year-old Brit Sam Jacques had his home searched and was charged with possession of a knife—in his own home—and was fined the equivalent of about $900. The knife fit the criteria of a category called a "zombie-style knife" and was therefore illegal in the United Kingdom, even though there was no evidence of wrongdoing or evidence that Jacques had any intention to harm anyone.

Named for blades commonly seen in zombie films, zombie knives are legally defined in the U.K. as a weapon with "(i) a cutting edge; (ii) a serrated edge; and (iii) images or words (whether on the blade or handle) that suggest that it is to be used for the purpose of violence." They were originally designed for collectors and survivalists. Jaques told the court he used the knife for bushcraft, building shelters, and other outdoor activities, and that the serrated part was used for cutting wires.

In 2016, under Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May, a new amendment to the Criminal Justice Act 1988 banned zombie knives after the fatal stabbing of an 18-year-old. Headlines named the assaulter the "Zombie Killer." Such knives are now categorized as "offensive weapons," along with more than 20 other weapons, including knuckledusters, butterfly knives, and telescopic truncheons. "Any person who manufactures, sells or hires or offers for sale or hire, exposes or has in his possession for the purpose of sale or hire, or lends or gives to any other person," can face six months to two years in prison.

In 2021, the government expanded the law further still, adding a ban on cyclone knives, defined as a "blade with a handle, a sharp point at the end and one or more cutting edges that each form a helix." Conservatives bragged about having some of the toughest knife crime laws in the world.

When a violent incident makes the news, politicians are quick to react with new regulations. Following the horrendous murder of three young Southport girls at a Taylor Swift-themed dance class, Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced a host of further knife restrictions. In an article for The Sun, Starmer wrote, "It remains shockingly easy for our children to get their hands on deadly knives." The root cause of the issue, Starmer said, was that the Southport murderer "was still able to order the murder weapon off of the internet without any checks or barriers."

In response, the government has announced new laws requiring online retailers, such as Amazon, to ask for two types of identification from anyone seeking to buy a knife. Customers would also face requirements to record a live video or selfie to prove their age.

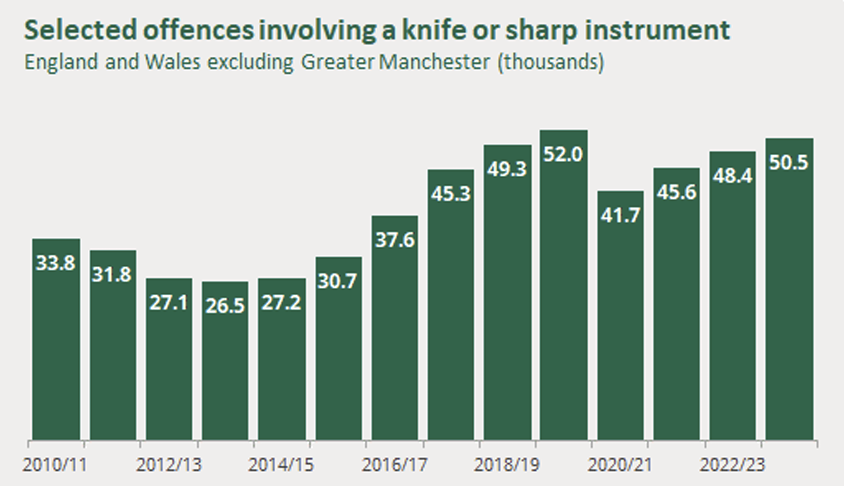

In the U.K., politicians have chosen to focus on the tools criminals use rather than the criminals themselves. The flaw with this approach is that it assumes people intending to break the law to assault someone will, for some reason, obey the law banning a certain weapon. By definition, criminals do not follow the law. Indeed, despite the various new bans, zombie-style knives remain readily available for purchase online, and violent attacks with zombie knives have still occurred since the ban. Incidents involving knives or other sharp instruments have not decreased. Between 2023 and 2024, there were more than 50,000 offenses involving a sharp instrument in England and Wales (excluding Greater Manchester), representing a 4.4 percent increase from the previous year.

Indeed, despite the U.K.'s extremely stringent gun laws, police recorded 5,103 offences in England and Wales in the year ending March 2025. Handguns have been banned since the 1990s, yet police recorded 1,665 offences involving handguns in the same year.

Non-violent citizens like Jacques, who have no intention of harming another person, are the ones who are penalized by these restrictions. While criminals can access knives and other weapons on the black market, those who want to stay on the right side of the law are left defenseless.

After a tragedy, it is politically easier for the government to send out a list of things they are going to ban, rather than answer difficult questions about policing effectively or dealing with the violent radicalization of young people. The Southport murderer, for example, received referrals to the government's anti-radicalization program three times before he committed the atrocious attack. Teachers warned officials that he was obsessed with violence. They failed to act. Instead of taking responsibility for running an abundantly inadequate anti-radicalization scheme—ironically called Prevent—the government chose to further restrict everyone's access to knives.

Another inconvenient phenomenon lies behind much of Britain's knife crime: gang violence, often a direct consequence of the war on drugs. The government's 2018 Serious Violence Strategy document explicitly links the rise in violent crime to the growth of county lines drug dealing:

"Violence can be used as a way of maintaining and increasing profits within drugs markets. There is good evidence that these dynamics are a factor in the recent rise in serious violence."

A sensible approach to tackling knife crime would include removing the incentive for criminal gangs to battle over drug markets. Instead, the government is doing the opposite: passing legislation that will eventually make tobacco illegal, introducing an entirely new front in the war on drugs, and creating a fresh income stream for violent gangs.

The frenzy and sensationalization of zombie knives in the U.K. serve as a warning to the rest of the world. The government blaming the weapon, rather than the perpetrator, is a recipe for never-ending restrictions on your liberty.

Show Comments (51)