Serious Immigration Law Enforcement Means Serious Destruction to American Liberty

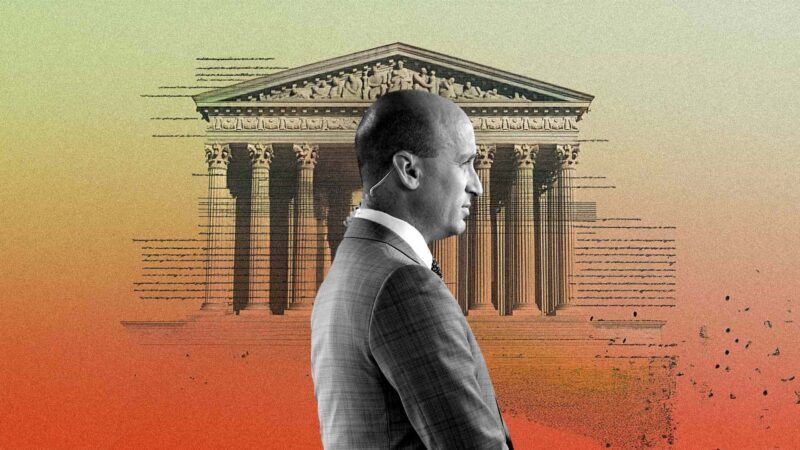

Stephen Miller's trial balloon about abrogating habeas corpus in immigration cases shows how any libertarian with pragmatic intelligence should reject so-called "libertarian" arguments for strict immigration laws.

Stephen Miller, the misguided immigration-obsessed Rasputin encouraging President Donald Trump's authoritarian overreaches to drive from the country people who the administration insists (but does not want to prove) are here illegally, has floated the administration's most tyrannical trial balloon yet: stabbing the very heart of what's decent in the Western legal tradition by saying the administration can and ought to eliminate the writ of habeas corpus in order to evade legal niceties preventing them from deporting as many people as they want, as fast as they want to.

As Jacob Sullum reported at Reason last week, Miller's untrue attempt to define illegal immigration as the sort of "invasion" that the Constitution does allow as an excuse to suspend the writ (though constitutional construction strongly suggests only Congress can actually do it) is prerejected by multiple federal judges, who have noted that "Trump's understanding of 'invasion or predatory incursion' is inconsistent with the law's historical context and with contemporaneous usage, including the definition of 'invasion' reflected in dictionaries, correspondence among the Founders, and the Constitution itself."

The writ of habeas corpus—in essence requiring the state to provide reasons and evidence before a court for holding someone in custody—is sensibly described commonly, as in this 1902 article in The American Historical Review as "one of the important safeguards of personal liberty, and the struggle for its possession has marked the advance of constitutional government."

One may quibble because the original Magna Carta specifies this as applying to "freemen," the positive trend in Western law has been applying its best standards to all people and in America everyone ought to be in essence a "freeman." Centuries ago our English legal tradition explicitly included in that Magna Carta that the King agreed that no one should be "taken or imprisoned…or outlawed or exiled or in any way ruined, nor will we go against such a man or send against him save by lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the land."

The libertarian movement has been infected by a heresy in the past few decades, springing from the writings of Hans-Hermann Hoppe, that allowed people temperamentally opposed to changes in the ethnic background of the people who live in this country to square a desire to manage that variable to their preferences with a self-image as a complete defender of total liberty.

The argument is more or less that a government should be able to, and ought to, behave as a private property owner of the public property it controls, especially when the restrictions it would impose seem to be wanted by a large number of the citizens of the country in whose name they manage the property. Following from that dubious proposition is the notion that it is no more a violation of the principle of nonaggression for a government to physically bar or remove someone from America who had committed no actual harm to any individual's person or property than it would be for you as a private homeowner to do the same barring or expulsion of someone you consider an intruder from your house or yard.

It's a shoddy argument that proves far too much about government's alleged proper power over behavior on "public property," though for whatever reason the pro-immigration-enforcement Hoppean "libertarian" never applies this line of alleged logic anywhere else. As Anthony Gregory and Walter Block explained in a Fall 2007 article in the Journal of Libertarian Studies, "Hoppe's position that keeping illegals off public property because of their supposed 'invasiveness' could easily be extended to other matters, aside from free trade. Gun laws, drug laws, prostitution laws, drinking laws, smoking laws, laws against prayer—all of these things could be defended on the basis that many tax-paying property owners would not want such behavior on their own private property." Only with actual individual private property, a libertarian recognizes, can whatever problem a Hoppean sees with human migration be solved. But that solution, Gregory and Block say, is written off by Hoppeans as "unrealistic" in the state-ruled world we currently live in.

But, the authors truthfully note, "even more [unrealistic] is the collectivist notion of the state keeping out immigrants in any way that emulates the market decisions and choices of the taxpayers. Since it is unrealistic, why even consider asking the government to do so? Between two unrealistic choices, why, on libertarian grounds no less, favor the one that necessitates state action?"

Even if one as a libertarian somehow believes that border control and keeping noncitizens out of the country was a legitimate government function justifying the use of force, applying even a tiny bit of real-world practical wisdom toward the practices necessary to try (even though they'd always fail) to achieve that goal should lead to the inescapable conclusion, however regretful for the dedicated Hoppean, that no libertarian could sensibly advocate the government actually try to sternly enforce immigration laws in the real world (even if such laws are theoretically justifiable).

Miller's announcement about eliminating habeas corpus for the purpose of kicking out who he wants to kick out makes perfect sense for his goals—though no sense at all for anyone with the slightest bit of respect for Western civilization or limited government.

An 1988 article in The American Journal of Legal History provides interesting context to the Miller controversy today. It tells the story of California judges who, against opposition both popular and judicial, insisted on allowing fair consideration of the writ of habeas corpus, and often vindicating the rights to remain, for many thousands of Chinese victims of threatened exclusion or deportation under the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Those who found such judges' concern for the rights of denied Chinese residents or would-be residents overly punctilious mocked their court as running a "habeas corpus mill." Indeed, many such mills will have to run if the U.S. government is to obey the law, and the Western tradition of justice, in its attempt to deport millions. (The 1868 version of the Burlingame Treaty between the U.S. and China, alas amended to be made far less libertarian in 1880 and paving the way for the Exclusion Act, in its Article 5 "provided for the reciprocal recognition of 'the inherent and inalienable right of man to change his home and allegiance' and the 'mutual advantage of the free migration and emigration' of people of both nations 'for purposes of curiosity, of trade, or as permanent residents.'")

Allowing government to ban or punish behavior that is victimless in the libertarian sense (and if one wants to argue that anyone who uses government services is victimizing taxpayers, that argument applies equally well to all your fellow citizens born here, yet is never offered as a legitimate reason to deport everyone) will inevitably lead to violating a wide swaths of rights in order to punish people who rarely have victims reporting the "crimes," who mostly only the state wants to punish.

If a law can't be enforced effectively while still honoring the basics of a limited government's responsibilities toward how to treat people it intends to physically harm, then it ought not be enforced—especially immigration laws, whose enforcement even beyond the procedural issues would be a devastating blow to American productivity and prosperity, all in the name of curtailing a practice that is overall more than fine for all Americans.

Yes, on occasion an illegal immigrant commits a horrific crime that would not have happened had they not been here. Still, advocating barring any of a conceivable class that committed a crime proves far too much to preserve even a semblance of limited government, and violates true justice, which must be about individuals and individual actions, not mere membership in some conceived group whose other members did wrong.

Immigration enforcement, like the enforcement of any law that mostly harms the harmless and prevents desired economic transactions that make things better for all sides, is impossible to do in a way that respects procedural or substantive justice. For the same reason drug law warriors want to toss away the Fourth Amendment, so do immigration hawks quickly reach the conclusion that the core protection of people from runaway government law enforcement is just an impediment to be wiped away in pursuit of their perverse goals.

It is not surprising that a government goal as unlibertarian as strict immigration law enforcement should lead ineluctably to throwing away the most precious protection against tyranny the West has produced and mostly honored; and anyone who calls for strict immigration enforcement is in essence calling, as Miller recognized, for the destruction of the centuries-old core legal protection against malignant tyranny, the writ of habeas corpus.

Show Comments (83)