Virginia Courts Won't Split Ownership of Divorced Couple's Embryos

"The unique nature of each human embryo means that an equal division cannot conveniently be made," writes a Virginia judge.

Property divisions during divorces can often be acrimonious, but for Honeyhline and Jason Heidemann the matter reached a whole new level of import. The couple couldn't decide who should retain ownership of the frozen embryos created with Honeyhline's eggs and Jason's sperm. This dispute has given rise to a novel legal case in Virginia.

A cancer survivor whose chemotherapy left her infertile, Honeyhline Heideman wanted to use the frozen embryos to conceive another child. She argued that ownership of the embryos could be addressed under Virginia's "goods and chattels" statute.

But in a March 7, 2025, opinion letter, Judge Dontae L. Bugg disagreed, dismissing Honeyhline Heidemann's suit and holding that "human embryos are not subject to partition" under Virginia law "as they do not constitute goods or chattels capable of being valued and sold."

Bugg goes on to suggest that there's no way that two embryos can be divided equally between two people because "the unique nature of each human embryo means that an equal division cannot conveniently be made."

You are reading Sex & Tech, from Elizabeth Nolan Brown. Get more of Elizabeth's sex, tech, bodily autonomy, law, and online culture coverage.

How the Heidemanns Got Here

The Heidemanns used in-vitro fertilization (IVF) in 2015. They conceived one daughter with the embryos that were created, and they cryogenically stored two remaining embryos. An agreement they signed at the time specified that any frozen embryos would be owned jointly but did not say what would happen in the event of divorce.

In 2018, the Heidemanns divorced.

At the time, the Heidemanns addressed the question of the frozen embryos in a Voluntary Separation and Property Settlement Agreement, stipulating that neither party would remove the embryos from storage "pending a court order or further written agreement of the parties" and that Honeyhline and Jason split the cost of storing the embryos.

In 2019, Honeyhline Heidemann sought her ex-husband's consent to use the embryos to conceive more children. Jason Heidemann said no.

Honeyhline next tried reopening their divorce case and filing a "Motion to Determine Disposition of Cryopreserved Human Embryos." But the court dismissed this, saying it no longer had jurisdiction over the Heidemanns' marital property.

Honeyhline then filed a Complaint for Partition of Personal Property, seeking a court order awarding her ownership of both embryos or, barring that, at least one embryo. Her request fell under the jurisdiction of Virginia's partition law.

This attempt also floundered at first, with a court holding in 2022 that the embryos were neither "goods or chattels" under the definitions supplied by Virginia statute.

But Honeyhline subsequently filed a motion to reconsider, and the case came before Judge Richard E. Gardiner.

"Although there are two cases involving disposition of cryopreserved embryos, those cases arose in the context of equitable distribution of marital property," Gardiner noted in a 2023 opinion letter. "Here, Ms. Heidemann is asking the court to partition the embryos as goods or chattels, as her request to address the embryos as marital property was denied in May 2020 for lack of jurisdiction."

Are Embryos 'Goods or Chattels'?

Jason Heidemann objected to his wife's motion, arguing that 1) a court couldn't order the embryos be treated differently than the ex-coupled had agreed upon in their earlier legal agreement, 2) allowing his ex-wife to conceive children with the embryos violated his 14th Amendment right to "procreational autonomy," and 3) the embryos were still not "goods or chattels" under Virginia's legal definition of such.

The constitutional argument is the most interesting, but Gardiner found that it was premature. Meanwhile, Gardiner found fault with Jason's other arguments. "Because the disposition of the embryos was not settled in the Agreement, the Agreement cannot be enforced as to the embryos and an order as to their disposition would be consistent with the Agreement," he wrote.

As to the question of whether embryos could count as goods or chattels, Gardiner pointed to the statute that would later become Virginia's current goods and chattels statute—a measure that once referred to the "division of slaves, goods or chattels." It's clear that the statute was not meant to apply only to "real property being partitioned," Gardiner concluded. Rather, it permits "the partition or, in the alternative, the sale, of 'goods or chattels' regardless of whether they are found on real property being partitioned."

Jason Heidemann had also suggested the law couldn't apply because it required an appraisal of the goods or chattels in question. Since it's illegal to buy or sell "human fetal tissue," embryos did not have a market value, he argued. And without a market value, the embryos couldn't be appraised.

But an embryo is not the same thing as "human fetal tissue," Gardiner pointed out in his 2023 letter.

"As there is no prohibition on the sale of human embryos, they may be valued and sold, and thus may be considered 'goods or chattels,'" Gardiner wrote, vacating the earlier court's ruling.

The Current Case

A few months later, Honeyhline Heideman re-filed her partition suit. The question of how to handle the Heidemanns' frozen embryos subsequently came before Judge Dontae L Bugg, who issued his ruling earlier this month.

Because Gardiner's 2023 ruling was an opinion letter, not an order of the court, it was not legally binding, Bugg pointed out. An opinion letter is merely "a written statement of a judge's reasoning for granting a motion to reconsider a dismissal order," he wrote.

And Bugg decidedly departed from the earlier judge's reasoning:

Insofar as the February 2023 Opinion Letter constitutes non-binding authority, the Court is not persuaded the "goods or chattels" include human embryos. The February 2023 Opinion Letter relies upon an earlier version of Virginia Code § 8.01-93 that authorized the partition of slaves to analogize that human embryos can be valued and sold to the extent that the statute is not limited to the partition of land. The Court takes issue with reliance upon a version of the statute that pre-dates passage of the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1865. For analysis purposes, while partition may be available for personal property not annexed to the land being partitioned, after full review of this matter, the analysis of the Opinion Letter is rejected as it relates to human embryos….

The removal of reference to slaves was solely to excise a lawless blight from the Virginia Code, the institution of slavery applicable to fellow citizens, which removal supports the principle that human beings, and by extension the embryos they have created, should not as a matter of legislative policy be subject to partition. The application of Virginia Code § 8.01-93 to cryopreserved human embryos is a strained construction never envisioned by the modem General Assembly and would not be in harmony with the context of the statute.

Bugg goes on to suggest that there's no way that two embryos can be divided equally between two people because "the unique nature of each human embryo means that an equal division cannot conveniently be made."

Admittedly, any analysis that likens embryos to slaves is a bit bizarre.

But Bugg's reasoning here is also unsatisfying. He seems to take offense at the idea that embryos might be subject to laws regarding division of property, and assures us that if it was a mistake to apply that law to human beings it's also a mistake to apply it to entities that could become human beings.

Yet the facts remain that these embryos exist, that something must be done with them, and that the parties that created them can't agree on what that something should be. Feeling that the law shouldn't apply to such matters, or that it's somehow undignified to to describe embryos as "goods," does absolutely nothing to change these facts.

Moving Forward

One thing Bugg's opinion does do a satisfactory job of is describing the murky and divided legal landscape concerning frozen embryos at present.

"Some jurisdictions have characterized cryopreserved embryos as property or a special type of property but have not determined whether embryos could be valued, bought, or sold," he notes:

Other jurisdictions have suggested that embryos are not property, but instead biological human beings that cannot be bought or sold and give rise to parental rights….

Other courts have suggested that embryos are not property but may give rise to ownership interests that put embryos in an interim category that entitles them to special respect due to their potential for human life.

The proliferation of IVF is sure to produce an increasing number of cases concerning ownership of or outcomes for frozen embryos. And these cases will collide with an increasing push to define personhood as beginning at fertilization.

Pretty much the only thing that's clear is we are destined for some difficult and heady arguments on this front.

As for the Heidemanns, Bugg has decided that since "partition in kind is inherently impractical," and since ordering a sale of the embryos "is neither legally sanctioned nor ethically acceptable," the courts can't really do anything to help them. He suggests that perhaps the legislature should address the issue.

More Sex & Tech News

No injunction on Florida social media ban: A federal judge will not block Florida's teen social-media law from taking effect. The ruling, issued Friday by U.S. District Judge Mark Walker, means the state can start enforcing a law that bans anyone under age 14 from having social media accounts and requires parental permission for 14- and 15-year-olds to have accounts.

"The law applies narrowly only to social media platforms with addictive features, like push notifications, with 10% or more of daily active users who are younger than 16 and who spend on average two hours or more on the app," WUSF reports. Walker said the platiffs—the tech trade groups NetChoice and CCIA—failed to show that they would be injured by the law.

"The broader fight by the technology companies against the law continues in federal court in Tallahassee," notes WUSF. "Walker's decision Friday was an interim ruling that focused narrowly on whether he would issue a preliminary injunction in the case."

What makes this ruling especially disappointing is that Walker appeared quite skeptical of the law during a recent hearing, likening the rationale behind it to prior panics over Dungeons & Dragons, comic books, and rap music.

A blow to California's Age-Appropriate Design Code Act: A federal judge has issued a preliminary injunction against California's Age-Appropriate Design Code Act (CAADCA), in a case also brought by NetChoice. U.S. District Judge Beth Labson Freeman "agreed that NetChoice was likely to succeed on the merits of its claims that the statute's prohibitions and requirements violate the online companies' expressive rights under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution," reports the Courthouse News Service.

"Even if the court were to accept that the act advances a compelling state interest in protecting the privacy and well-being of children, the state has not shown that the CAADCA is narrowly tailored to serve that interest," wrote Freeman in her ruling. "The act applies to all online content likely to be accessed by consumers under the age of 18, and imposes significant burdens on the providers of that content."

"While protecting children online is a goal we all share, California's Speech Code is a trojan horse for censoring constitutionally protected but politically disfavored speech," said NetChoice director of litigation Chris Marachese in a statement.

Texans gonna Texan: A new measure proposed by Texas state Rep. Briscoe Cain (R–District 128) would ban public employees from listing their pronouns in any work communications or, in the course of their job, using terms that include "sex workers," "pregnant people," "pregnant Texans," or "abortion care."

Ron Wyden on why the Internet still needs Section 230:

Across U.S. politics, it's become fashionable to blame nearly all the internet's ills on one law I co-wrote: Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. Everyone from President Donald Trump to some of my Democratic colleagues argue that Section 230 has let major tech platforms moderate too much or too little. Trump's Federal Communications Commission chairman, Brendan Carr, has already written about his plans to reinterpret the law himself.

Many of these claims give Section 230 too much credit. While it's a cornerstone of internet speech, it's a lesser support compared to the First Amendment, as well as Americans' own choices in what they want to see online. But I'm convinced the law is just as necessary today as when I co-wrote it with Rep. Chris Cox in 1996.

Trump continues Biden-era investigation into Microsoft: The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) "is moving ahead with an antitrust probe of Microsoft that was opened in the waning days of the Biden administration," reports Reuters. "The investigation was approved by then FTC chair Lina Khan ahead of her departure" and centers on Microsoft's licensing terms for cloud services and its deal with OpenAI. It looks like the Trump administration is going to continue the tedious, counterproductive antitech antitrust crusade it started in Trump's first term and which was ramped up under Khan.

Encryption attacks abound abroad: Wired reports:

Over the past few months, there has been a surge in government and law enforcement efforts that would effectively undermine encryption, privacy advocates and experts say, with some of the emerging threats being the most "blunt" and aggressive of those in recent memory. Officials in the UK, France, and Sweden have all made moves since the start of 2025 that could undermine or eliminate the protections of end-to-end encryption, adding to a multiyear European Union plan to scan private chats and Indian efforts that could damage encryption.

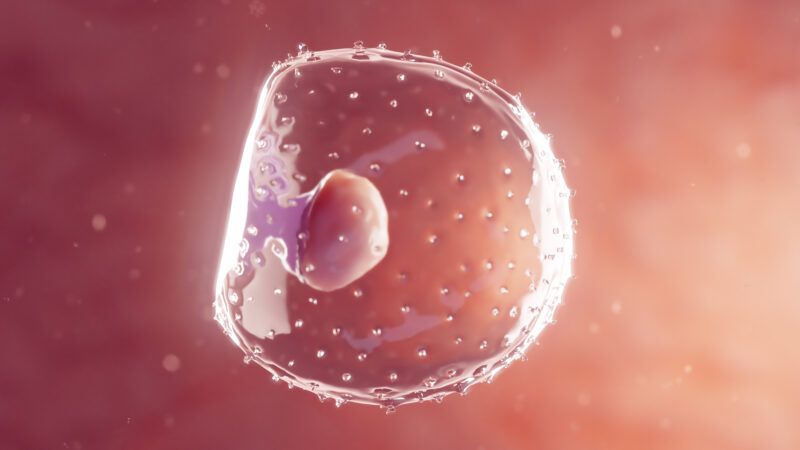

Today's Image

Show Comments (81)