What If Native American Tribes Had Gotten Their Own State?

Historian Donald L. Fixico explores a forgotten moment in Oklahoma history and its lessons about liberty.

The State of Sequoyah: Indigenous Sovereignty and the Quest for an Indian State, by Donald L. Fixico, University of Oklahoma Press, 206 pages, $34.95

In McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020), the Supreme Court rejected Oklahoma's attempt to prosecute crimes committed on a reservation by an Indian. Henceforth, the tribe, not the state, would have jurisdiction over Indian crimes on Indian lands. It was such a win for Indian sovereignty that the Muscogee have dubbed July 9, the day the decision came down, as Sovereignty Day.

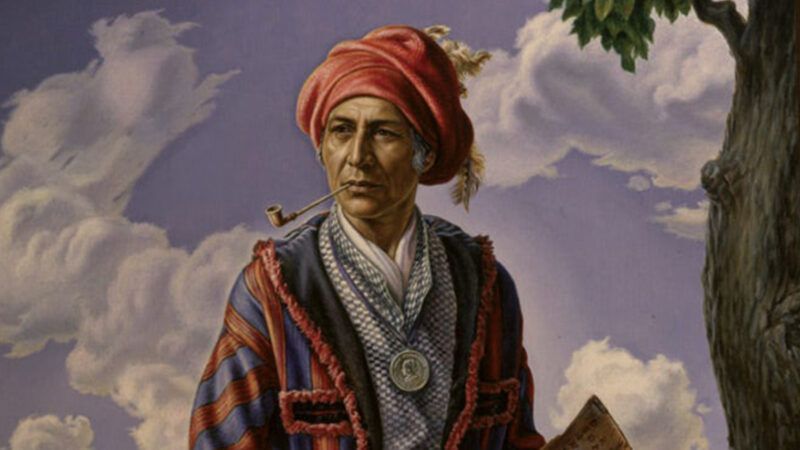

If history had taken a different turn, the place now known as Oklahoma could have seen an even stronger win for Native American sovereignty. That area was once known as Indian Territory: a land where tribes displaced from other parts of the U.S. had been resettled. In 1890, a part of it was carved out to form the Oklahoma Territory, but a large portion of what is now the state of Oklahoma remained in Indigenous hands. Even as the Oklahoma Territory applied for statehood, so did the Indian zone. On November 7, 1905, delegates from the Five Tribes—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole—met in Muskogee, Oklahoma, at the Hinton Theater. They voted overwhelmingly to support a constitution for a proposed state of Sequoyah, named for the Indian who was the first to write down the Cherokee language.

They lost that fight: When Oklahoma was admitted to the Union in 1907, the Indian and Oklahoma territories were consolidated into a single state. But in The State of Sequoyah, which relates the history of that battle and of the larger idea of an Indian state, the Arizona State University policy historian and ethnohistorian Donald L. Fixico makes a case for the continued relevance of such ideas. "If the District of Columbia or Puerto Rico are possible candidates for statehood, then so should be the state of Sequoyah," he argues.

The Five Tribes were not actually "tribes" in the sense that most people use the word today: They consisted of autonomous townlike communities, each with their own histories and their own systems of property and governance. In the decades that followed their removal from the East, the Five Tribes revised their traditional infrastructures, adopted constitutions, and, in Fixico's words, "began endowing a central, collective sovereignty."

Fixico demonstrates how deeply ingrained the idea of an Indian state is in the history of Indian-white relations. The concept itself goes back at least as far as the Treaty of Fort Pitt, signed on September 17, 1778, which promised the Delaware Indians an offer "to join the present confederation, and to form a state whereof the Delaware nation shall be the head, and have a representative of Congress." Needless to say, this was not how we got the state of Delaware. The new nation's first treaty with an Indian nation was, thus, also the first to be broken.

Secession provided another opportunity. The Confederacy promised Indian Territory statehood in exchange for support, and many Native nations provided soldiers to the Confederate cause. That path to an Indian state disappeared when the South lost the war.

During Reconstruction, the federal government forced the Five Tribes to unify into a single structure, though each retained a degree of autonomy and each sent delegates to the convention for statehood. The Reconstruction-era government also trampled tribal sovereignty by asserting federal authority over all major crimes, even though the Five Tribes had their own courts and their own police. After Reconstruction, the Dawes Act of 1887 broke up the tribes' landholdings and imposed a system of individually held property whether or not the Indians involved wanted it. (In practice, this was used to free up land for white settlers.) The Curtis Act of 1898 continued the reorganization of Native property rights and also abolished the Five Nations' tribal courts.

At the end of the 19th century, the government repeatedly and continually opened more land for settlement in the area that is now Oklahoma. The land rushes of 1889 and 1891 together opened more than 2 million acres of land for settlement. In 1893, 100,000 people participated in the biggest land run in American history: the Cherokee Outlet Run.

The land rush included not just whites but around 3,000 African Americans. Many of these new arrivals offered yet another political vision: a black state in Indian Territory. Oklahoma clubs in Kansas hoped to establish black homesteads and all-black towns. Many of these migrants were former slaves of masters from the Five Nations. Some of them wanted to settle on the Unappropriated Lands in Indian Territory—that is, those lands within Indian Territory that were not settled by Indians.

Some Indians resisted black settlers, wanted freedmen removed from their reservations, and had their governments formally forbid intermarriage with African Americans. Oklahoma Territory legislators tried to drive out black settlers too and adopted segregationist policies. They certainly weren't willing to make room for a black state.

The dream of an Indian state died as well: President Teddy Roosevelt decided it was against "Republican policy" to form two states from the region, and the single state of Oklahoma was admitted instead. (Republican policy are the words the Indian delegates who met with Roosevelt used to describe his stance. It is not clear what policy the president was referring to.)

It is hard to say in retrospect how close Indians were to securing their own state, though Fixico shows there was a substantial consensus within the tribes in favor of forming one. If Roosevelt had been more supportive, or if "Republican policy" had allowed it, there may have been an opportunity for Congress to consider the idea. But the lack of support from the top of the Republican administration seems to have doomed the proposal.

In the wake of that failed fight, there would be many more reminders of why so many Natives wanted a state of their own. Indians continued to face forced assimilation into the white American mainstream, and after World War II the federal government tried to eliminate tribal sovereignty outright—a time known as the Termination Era, because Washington explicitly aimed to assimilate tribal governance into the state and federal governments. Not until the 1960s did President John F. Kennedy start putting the brakes on termination, and not until the 1970s did self-determination become national policy.

Even after that, Congress asserts powers over Indian country that it does not claim over the states, such as authority over major crimes. Even after McGirt, the Supreme Court has yet to reject the notion that Indians are a "domestic dependent" nation. Paternalism continues to be the overarching principle: Most reservation land is held in perpetual federal trust.

Would an Indian state offer more autonomy? As James Madison argued in Federalist No. 45, the powers reserved to the states are "numerous and indefinite." Tribal sovereignty is more circumscribed and limited. An Indian state would perhaps offer greater autonomy for Native Americans than the current reservation system.

Fixico does not explore what an "Indian state" would look like today. Sequoyah would have occupied a specific contiguous area, with special emphasis on the Five Tribes. What an Indian state could be today, given that there are 574 federally recognized tribal entities, is not clear, but that does not seem to be the point. The point is that if a collection of Indian people wanted to unify and propose a state, or some other alternative to the current reservation system that would align with the conventional system of American states, it shouldn't be considered outside the realm of possibility. The book does not aim to advance any specific proposal; it wants to acknowledge that this is an option to take seriously, if Native nations themselves are interested in it.

For those interested in promoting liberty and autonomy, and in righting the historical wrongs caused by government overreach, such a state could be a reasonable way to promote political freedom. Reading Fixico's scholarship and thinking of those 50 stars on the American flag, I couldn't help asking: Why not a few more?

Show Comments (167)