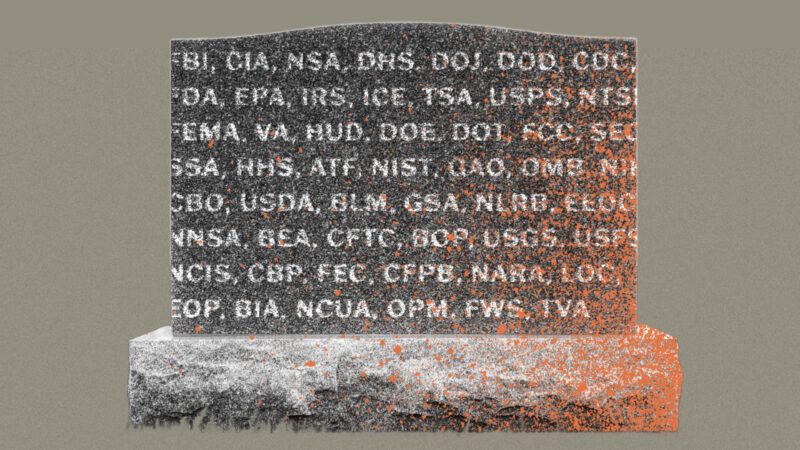

RIP to Government Acronyms

One perk that may materialize from Elon Musk upending the federal bureaucracy is the downfall of the government’s obsessive use of abbreviations.

From the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Elon Musk is on the warpath to devour the alphabet soup of the federal bureaucracy. "We do need to delete entire agencies, as opposed to leave part of them behind," said the world's richest man and President Donald Trump's consigliere.

One perk that may materialize from his disruptive (and legally dubious) actions is the downfall of one obnoxious governmental institution: abbreviations.

"Acronyms seriously suck," read the subject line of an email Musk sent to his entire SpaceX team. In his email, he explained how the "excessive use of made up acronyms is a significant impediment to communication."

Musk is no stranger to arbitrary abbreviations. He created the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), an obvious tip of the hat to his favorite pump-and-dump cryptocurrency named after the beloved, wide-eyed Shiba Inu. Musk has also attained the designation of a special government employee (SGE) to wreak havoc on the federal landscape.

DOGE and SGE are just droplets in the seemingly endless stream of government abbreviations. Milton Friedman famously joked, "Pick at random any three letters from the alphabet, put them in any order, and you will have an acronym designating a federal agency we can do without."

Like many, Friedman conflates acronyms and abbreviations. Acronyms are pronounced like words (e.g., NATO, FEMA, NASA), and initialisms are the composite of their individual letters (e.g., FBI, CIA, EPA).

Grammatical pedantry aside, Musk and Friedman aren't wrong about the government's incessant use of abbreviations.

The Age of the Acronym

There is no shortage of abbreviations in Washington, D.C. The U.S. Government Manual lists hundreds of cabinet-level departments, independent agencies, regulatory commissions, and government corporations and their accompanying abbreviations.

And like a Russian nesting doll, each entity houses its own endless array of abbreviated jargon. The Department of Defense leads the way with over 4,000 abbreviations in its internal dictionary.

Driving this Matryoshka-esque multiverse of abbreviations is lawmakers' love of acronyms. Legislators often reverse-engineer acronyms (or "backronyms") to create memorable mnemonic devices to market their legislation. Assuredly, bill nicknames like "STOP SMUT" roll off the tongue better than the Special Taxation on Pornographic Services and Marketing Using Telephones Act. But the acronym can also be overly contrived and forced, such as the recently introduced "Eliminating Looting of Our Nation by Mitigating Unethical State Kleptocracy Act," or the ELON MUSK Act.

A backronym-named law can mask harmful policies by wrapping itself in flag-waiving euphemisms, as we learned with the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001, or the USA PATRIOT Act.

Other countries also struggle to address their obtuse government communications. George Robertson learned this lesson during his early tenure as the British secretary of state of defense. With unrest in the Balkans and the Middle East threatening international stability, Robertson took office during a tumultuous time. In addition to imminent global peril, Robertson wanted to address his agency's overuse of abbreviations. After listening to his boss's plan to simplify agency terminology, Robertson's chief of staff, Sir Charles Guthrie, leaned toward his boss and said, "I think that you'll find solving Bosnia will be easier, Secretary of State."

French President Emmanuel Macron recently undertook the unenviable task of simplifying his country's "labyrinthine bureaucracy." "We have nothing but acronyms," Macron said during a meeting with French business leaders. "It's awful." After proposing consolidating multiple subsidies into one program, Revenu Universel d'Activité, Macron pleaded with his constituents not to abbreviate it. "I ask you one favor: Don't call it RUA," said Macron. "Acronyms lock people in boxes."

Abbreviations have increasingly entrapped our global vernacular. Australian scholars Adrian Barnett and Zoe Doubleday analyzed 24 million scholarly articles published between 1950 and 2019. Barnett and Doubleday found abbreviation usage more than doubled during that time. That growth was fourfold in abstracts alone. Interestingly, of the 1 million unique abbreviations Barnett and Doubleday identified, about 2,000—less than 1 percent—were repeated, meaning scholars are abbreviating for the sake of abbreviating. Most abbreviations—nearly 80 percent—appeared fewer than 10 times.

"I may have grown up in the Age of Aquarius," writes grammarian Roy Peter Clark, "but I'm growing old in the Age of the Acronym."

People 'H8' Abbreviations

Research suggests most people agree with Musk: Abbreviations "seriously suck."

David Fang, a doctoral student at Stanford University, found that people who use texting shorthand—LOL, BTW, BRB, TY, etc.—may struggle to communicate with others. "We found that when people use abbreviations, others think they're putting in less effort, which makes them seem less sincere, and so they are less likely to get a response," said Fang.

People's objection to abbreviations boils down to perception and cognition. Alyssa Appelman, a researcher and journalism professor at the University of Kansas, presented test subjects with similar news articles with manipulated headlines—e.g., "National parks offer free admission for Martin Luther King Jr. Day" vs. "US parks offer free admission for MLK Day." Appelman found that readers demonstrated increased frustration when reading the latter. "Readers don't seem to be inherently bothered by the presence of acronyms in headlines," Appelman explains. "They seem to be bothered by the ones they don't understand."

This frustration feeds into an overall distrust of institutions. Appelman demonstrated that those who struggled with the abbreviations already demonstrated a negative view of the media. Whether this trend is causative or correlative is unknown. But this self-perpetuating feedback loop certainly doesn't diminish their greater distrust. And with public trust in media and government at an all-time low, it's safe to assume this skepticism bleeds over into other legacy institutions.

These negative perceptions also unnecessarily fuel our culture wars. Polling finds a wide partisan divide for abbreviations like DEI, CRT, and ESG. However, when researchers swapped abbreviations for their broader long-form versions (e.g., "equity" instead of DEI and "sustainability" instead of ESG), the partisan divide shrunk. Specificity—, something lacking in most abbreviations— may be part of the antidote to our political toxicity.

Government Abbreviations Are Technically Illegal

In 1948, Sir Ernest Gowers, a decadeslong British civil servant, famously wrote Plain Words. The 94-page pamphlet—which popularized the famous maxim "be short, be simple, be human"—kickstarted the plain language movement. For decades, this movement, with a penchant for clarity and brevity, has championed communications that laypeople could easily access and understand. More importantly, plain language opposes abbreviated government gobbledygook.

It wasn't until recently that governments adopted and codified plain language standards. On October 13, 2010, President Barack Obama signed the Plain Writing Act into law. The law required federal agencies to "improve the effectiveness and accountability" of federal agencies and promote communication that the "public can understand and use." The act also requires agencies to use plain writing in public-facing documents, train employees in "plain writing" practices and standards, and establish meaningful ways for the public to communicate with the agency.

Plain language specifically targets abbreviations. The federal government's plain language website encourages government employees to "keep it jargon-free." Instead of abbreviations, government communication professionals should "use full words" (Vice President, not V.P.) or "use an alternative" (computer memory, not RAM). If abbreviations are necessary or if spelling them out "would annoy your readers," plain language guidelines encourage writers to minimize abbreviations to "a maximum of two a page."

Obviously, plain language is legally toothless. Government abbreviations are the equivalent of jaywalking: technically illegal but lightly policed. Ironically, the leading federal group—Plain Language Action and Information Network (PLAIN)—identifies as a backronym.

Abbreviations are not inherently wrong. When used to address broadly familiar entities like the FBI or EPA, abbreviations can save space and expedite communications.

However, speed is useless when it lacks context. When used excessively, abbreviations can also be, as plain language expert Joseph Kimble put it, a "menace to prose" that distracts and confuses readers. Even worse, citizens can become so accustomed to jargon-dense, euphemistic language that they ignore policies that directly affect or harm them. Ask your average Joe what NDAA stands for, and you'll be lucky if they can name the National Defense Authorization Act, let alone the billion-dollar megalomania it codifies.

Tackling the federal bureaucracy and its overuse of abbreviations is not for the faint of heart. Considering the size and scope of the federal government and the need for congressional action to actually abolish federal agencies, Elon Musk certainly has his work cut out for him. And if reducing the size and scope of the federal government is a Herculean task, cutting government abbreviations will be Sisyphean.

However, if they intend to procure legitimacy and garner public support, public officials must kick their nasty habit and heed the sage advice of plain language advocates: "Let abbreviations and acronyms RIP."

Show Comments (322)