Everybody Hates Prices

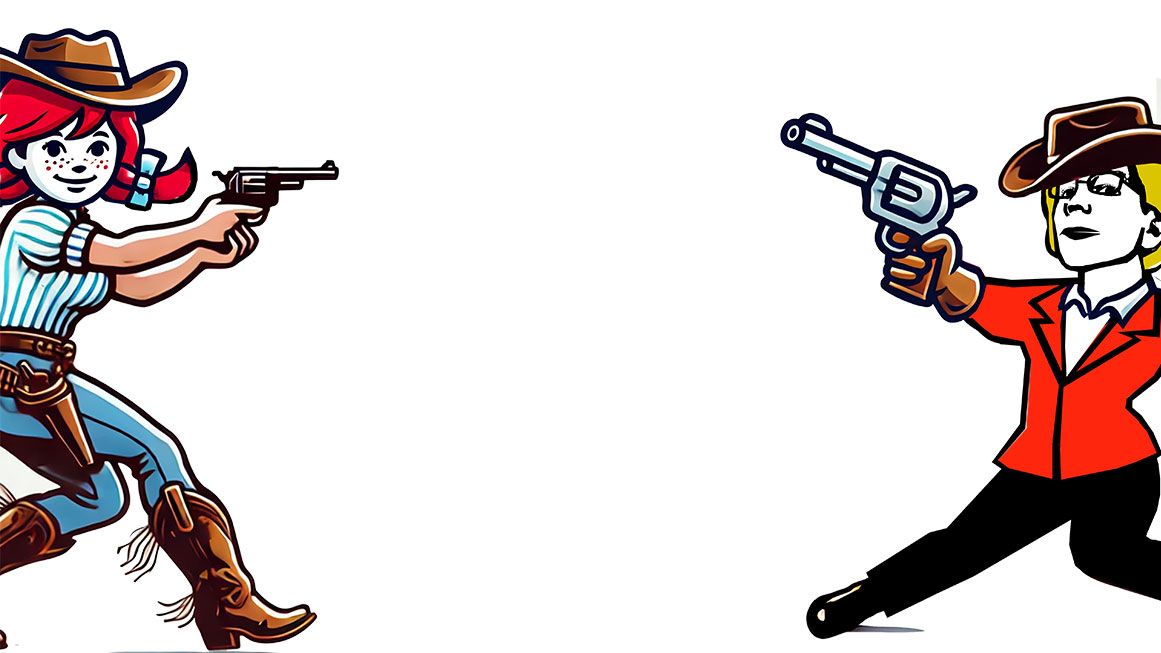

How much should a Wendy's Baconator cost? Elizabeth Warren thinks the government should help decide.

The Wendy's Baconator is a beast of a burger. Introduced in 2007 as part of a back-to-basics rebranding of the perpetual fast-food underdog, the Baconator consists of a half-pound of beef, multiple slices of gooey American cheese, and six pieces of bacon, plus condiments. It contains 57 grams of protein and just shy of a thousand calories—about half the daily recommended intake for an average person, and more than twice the average caloric intake of the estimated 800 million people globally who are perpetually undernourished.

How much would you pay for a miracle food like the Baconator? How much should you pay? Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.) has some ideas.

In February, Wendy's CEO Kirk Tanner announced the burger chain would invest $20 million in digital menus. These virtual menu screens would allow the company to experiment with dynamic pricing—which is to say, pricing that changes regularly based on circumstances.

Tanner's announcement led to news stories saying the company planned to test out "surge pricing," a strategy most commonly associated with ride-sharing companies whose prices rise with demand. Try hailing an Uber at rush hour, or after a big game in a downtown area, and you'll pay more than you would for the same ride on a quiet weekday afternoon. Wendy's, the stories suggested, might be planning to charge more for its meals during lunch and dinner rush hours.

Warren wasn't having it.

On X, she wrote that the move meant "you could pay more for your lunch, even if the cost to Wendy's stays exactly the same." That would not be acceptable. "It's price gouging plain and simple," she wrote, "and American families have had enough."

One is tempted to respond, "Senator, this is a Wendy's."

Wendy's eventually clarified there were no plans to introduce surge pricing in their dining rooms. But as is so often—and so unfortunately—the case, Elizabeth Warren had a plan. Two years earlier, she'd introduced a bill, the Price Gouging Prevention Act of 2022, that would have given the federal government sweeping power over the price of food and other goods.

Characterized by its supporters as a sensible federal expansion of existing price gouging laws, necessary to combat rapidly rising inflation, the bill text declared it "unlawful for a person to sell or offer for sale a good or service at an unconscionably excessive price during an exceptional market shock." To prevent this sort of extreme pricing, the bill would have empowered the Federal Trade Commission to block, investigate, and fine any company, in any part of a supply chain, from retail sellers to wholesale producers, who participated in a scheme to charge an "unconscionably excessive price."

What sort of price hike would count as "unconscionably excessive"? The bill didn't define the term, leaving that to federal bureaucrats to decide. But given Warren's outrage at Wendy's supposed surge pricing, one suspects that variably priced Baconators in the years after a pandemic might have qualified.

I will grant that the carnivorously bloated Baconator itself might be unconscionably excessive as a foodstuff. But Warren's online complaints and history of legislative threats hinted at something far worse: a proposal for what amounted to federal price controls.

Warren's price gouging law was introduced in 2022, as postpandemic inflation brought surging prices for groceries, gasoline, automobiles, housing, and the computer chips necessary for everything from AI to video game consoles. The Wendy's fracas came two years later, as the rate of inflation cooled but, thanks to stubbornly elevated prices, food costs remained a top issue for voters.

What all of it revealed was something that economists, historians, and inflation experts know all too well: People hate prices. They hate rising prices. They hate persistently high prices. They hate complicated prices. They hate resort fees and bag-check charges and delivery costs and service fees. At times they even hate falling prices, like on homes they already own. They even hate flat, dependable, unlimited-use subscription prices when they have too many of them.

It's not too hard to understand why people hate prices. Prices, left to do their work, are signals—about value, about rarity, about cost in time and resources, about sentimentality, about desirability, about the labyrinthine machinations of global supply and demand.

Prices, in other words, deliver information. And in many cases, the information they deliver is that you can't have everything you want.

Politicians like Warren, meanwhile, are in the business of falsely promising that actually you can. Failing that, they are in the business of masking, manipulating, capping, controlling, and otherwise distorting prices in hopes of hiding the information that prices convey. Price controls and their ilk are a politician's way of lying to you about what something is worth.

It's not just Elizabeth Warren. As inflation surged, politicians from both parties, including presidential nominees Donald Trump and Kamala Harris, sought to cap or control prices for food, credit, medical care, labor, and more. Activists have concocted narratives about intensifying corporate greed, and academics have pushed sweeping price controls in response.

In other words, price controls have returned to the center of American political discourse. But there is no reason to think they have suddenly become valuable tools of public policy. On the contrary, price controls are just as dangerous and destructive as ever—and just as appealing to clueless politicians.

A Nation of Price Controls

Despite certain pretenses to being a country with free markets, if you look around at the American economy you'll see signs of price controls all over.

Take alcohol: More than a dozen states are "control states" that centrally plan distribution and fix prices. Price controls on liquor keep prices down, but they also create shortages, since there's no incentive to make more product available when demand increases. That means rare, sought-after bottles are often snapped up by flippers to be resold on the secondary market. It has also led to a series of scandals, in Virginia and Oregon, in which state employees were caught manipulating supply chains in order to snag or sell valuable bottles of rare liquor.

In health care, price controls and price restrictions are the norm. Medicare, the federal health financing program for seniors, is the largest payer in the sector nationally, and its complex payment schedule provides an anchor for payers of all sorts, distorting prices even in nominally private transactions. Many of those transactions are facilitated via employer-sponsored health insurance, which is exempt from taxation. Most employees who obtain health insurance through work only pay a fraction of the total cost, masking the true cost of care. The tax carve-out for employee benefits such as health coverage, meanwhile, was an outgrowth of World War II–era wage and price controls that has persisted for decades since.

The result is a system in which prices are opaque, meaning that real price signals—information about supply, demand, scalability, flexibility, and so forth—are almost entirely absent. American health care is incredibly expensive, eating up ever-larger portions of paychecks, employer costs, and the federal budget. Price controls intended to make lifesaving care more affordable have instead made medicine expensive and frustrating to access. By masking and distorting price signals, they have contributed to health care's ever-growing grip on American fiscal policy.

Not all price controls are price caps. Some are price floors, which can have equally distorting effects on supply and demand.

Consider minimum wage laws, which specify a minimum price for labor. In theory, minimum wage laws guarantee a fair price for unskilled labor, helping powerless workers avoid exploitation by cruel paymasters. In practice, minimum wage requirements drive up prices for consumers, and they can make it harder for the least skilled workers to find work by raising the price of low-skilled labor beyond what employers can afford to pay.

There may be no realm of price controls that has been more obviously counterproductive than rent regulations, which have contributed to shortages and high housing costs across the country. Their toll is clearest in New York City, where about a million apartments are subject to some form of rent stabilization or, less often, rent control. Rent control's defenders say it's vital for ensuring there is sufficient affordable housing in what is otherwise a very high-cost city. Yet study after study—not to mention just about everyone who has ever moved to the city—has found that rent regulations intended to restrict price increases make housing in the city less available and, thus, less affordable. New York's housing market is among the most regulated in the country, and one of the most expensive.

Yet in 2024, President Joe Biden proposed what amounted to a nationwide system of rent caps, pushing Congress to pass a law instituting a cap of 5 percent on rent increases by corporate landlords, who would risk losing certain tax breaks if they failed to stay under the cap. The first line of a White House fact sheet declared that Biden was "taking action to make renting more affordable for millions of Americans." The history of rent regulations suggests that Biden's plan would do no such thing. But the allure of price controls persists.

Price controls are an appealing lie: They are premised on the notion that officials can stop cost increases by fiat from on high. Every price regulation is a claim that prices can be controlled by politics.

Politicians keep making this claim because voters tend to like it. In 1971, after years of high inflation, especially in the food and energy sectors, President Richard Nixon shocked the world by "ordering a freeze on all prices and wages throughout the United States for a period of 90 days."

Nixon's gambit was, by virtually every measure, an abject failure, presaging a decade of high inflation and shortages of basic goods, especially gasoline, with long lines at the pump becoming a fixture for many Americans. But voters reelected him, and then he imposed wage and price controls again after winning a second term. Polls showed three-quarters of the country approved of his initial plan. Americans were tired of prices and the unpleasant information they provided. Nixon won their favor by promising to shield them from the economic reality that prices described.

The War on Prices

The best case for price controls goes something like this: They worked. Once. And if smartly designed and targeted, they could work again.

In August 2022, as Americans reeled from the highest rate of inflation in more than a generation, historian Meg Jacobs and economist Isabella Weber argued in The Washington Post that "Congress can stabilize prices and reduce inflationary pressures through selective price caps combined with investments to increase the resilience of our economy."

Jacobs and Weber acknowledge that price controls have "a bad reputation politically and a record of mixed success," which, if nothing else, is a funny way to describe a vast system of government-enforced rationing. But they claim price controls worked during World War II, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt capped wages and prices across the economy, intent on keeping the nation's industrial output focused on the war effort. Goods like meat and fuel were distributed via ration cards, which, they say, "ensured a fair supply at controlled prices." Jacobs and Weber argue these measures were justified because inflation fell, the poor experienced a better standard of living, and inflation spiked after price controls were lifted.

That might sound like a strong case for price controls. It's not.

In an essay in the 2024 book The War on Prices, Cato Institute economist Ryan Bourne mounts an extended critique of World War II's price controls, arguing that Jacobs and Weber's data paint an incomplete picture of the economy.

Citing work by economists Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, he points out that "price increases took indirect and concealed forms not recorded in the indexes." Letters from the era, for example, show that basic foodstuffs were often replaced with lesser goods—say, cereal mixed in with coffee, or dried grass sold as tea, or meat swapped with lower-quality cuts—or with smaller portions for the same price.

Because price increases were suppressed, in other words, quantity and quality went down, acting as hidden price hikes. As Bourne writes, the negative effects of price controls are noted in U.S. government reports from the era, with a 1943 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics document stating, "We believe that consumers' goods and services, in the aggregate, have since 1939 suffered some loss of quality that is not reflected in reported prices." The inflation surge that took place after the controls were lifted merely reflected the real underlying price increases that had occurred under the restrictions. Price controls temporarily masked price increases; they did not alter the economics of supply and demand.

But price control policies are never really about economics. They are about politics.

Price regulations are manifestations of the lie that politics can somehow supersede or redirect a vast economy's fundamentals by fiat. Indeed, Jacobs and Weber argue that the key to effective price controls "lies in politics: a strong alliance and a broad-based social commitment are crucial for the effective implementation of selective controls as a way to tamp down inflation."

The desire to suppress prices has persisted in American politics through the Biden era and the 2024 presidential campaign. On the right, former President Donald Trump blasted credit card issuers and threatened to cap interest rates at 10 percent, which, if implemented, would radically reduce the availability of credit.

On the left, Democrats in Congress and progressive intellectuals argued that rapidly rising prices were a product of corporate greed. This idea was self-evidently silly: Why would corporate greed have, all of a sudden, caused prices to spike? The truth was more prosaic: Pandemic supply chain disruptions and a multitrillion-dollar influx of government cash into the economy had crimped supply and boosted demand.

Meanwhile, during her campaign for president, Kamala Harris proposed a price gouging ban in response to high grocery prices. The minimally sketched out plan was vague enough to result in multiple interpretations, with some suggesting it could amount to a sprawling system of federal price controls, and others insisting it would be more like the little-used state bans on price gouging during emergencies.

The point of Harris' proposal wasn't really to articulate a clear mechanism for government management of prices: It was, as always, to promise that politics could suppress the irksome information that prices provided.

The Price of Everything

At heart, prices are about value. Value changes from moment to moment, depending on context and circumstances.

Consider the market for American whiskey. Until sometime in the early 2010s, bottles of W.L. Weller 12 Year bourbon and its brand-mate Weller Antique typically cost somewhere in the range of $30 to $50. You could find bottles all over the country, and markups were essentially unheard of.

But in the early 2010s, bourbon collecting began to take off, with sought-after bottles fetching enormous prices. No bourbon was in greater demand than Pappy Van Winkle, a line of limited releases that was sometimes described as the best bourbon in the world. It was certainly the most expensive, with hard-to-find bottles fetching thousands, and sometimes tens of thousands, of dollars at auction.

As Pappy shot up in price, bourbon fans discovered it was made from essentially the same underlying product—with the same grain mix, the same distillation process, and the same aging location—as Weller's offerings. Pappy was selected from the best of the barrels that produced Weller; Weller, then, was just Pappy that didn't make the cut. A recipe circulated online showing how a bourbon enthusiast could make "poor man's Pappy"—an approximation of the much more expensive product—by combining two expressions of Weller.

Suddenly those easy-to-find, inexpensive bottles of Weller became much harder to find, and much more expensive, pushing well into the three-figure range. Nothing had changed about the product, the cost to make or distribute it, or the available supply. But circumstances had changed. Demand had increased based on new information. The perceived value of any given bottle had increased. This is the information that prices reveal.

Which brings us back to the Baconator. How much should a Baconator cost? The answer is: It depends.

It depends on where in the country you are; how hungry you are; and how much you like Wendy's, and hamburgers, and bacon. Despite Wendy's assurances that it won't institute surge pricing with higher prices during times of peak demand, it might even depend on the time of day. After all, there's more demand around lunch and dinner. The Baconator doesn't change then, but the context and circumstances do.

That can happen with hamburgers. Around the time Sen. Warren was flipping out about Wendy's menus, another story was unfolding elsewhere in the world of fast food.

During summer 2024, Wendy's biggest rival, McDonald's, announced it had missed its second-quarter revenue estimates. Inflation had eaten into customer budgets, and people were pulling back on spending. From 2019 to 2024, McDonald's prices increased by about 40 percent. At the same time, McDonald's CEO Chris Kempczinski said, "Eating at home has become more affordable."

So McDonald's changed tactics. It introduced a limited-time meal deal special, consisting of a burger or chicken sandwich, four chicken nuggets, french fries, and a drink—for $5.

The meal deal was a hit, and McDonald's execs eventually announced plans to extend it through the end of 2024. Business had picked up, and McDonald's customers had cheaper options.

Did McDonald's suddenly become less greedy? Far from it. Prices delivered useful information, and the fast food managers acted on it, to everyone's advantage.

Pricing shifts produced changes in consumer behavior—a signal that fast food costs too much. In response, the market leader created a new product, a new bundle, designed to send its own message. Prices, and the reactions to them, constituted a kind of discussion between McDonald's and its potential consumers, a negotiation of acceptable terms. In the end, everyone was better off.

This is why it's foolish to hate prices, and why they provide so much value—not only to businesses, but to consumers. Prices don't just provide the information that you can't have everything you want. They help you understand how to get what you want. Prices help people prioritize, manage, and allocate scarce resources, at home and in the boardroom. They are tools for making better decisions.

Despite Elizabeth Warren's protestations, there's no single right price for a hamburger. Nor is there a single correct price for housing, or health care, or eggs, or gasoline, or checked bags, or neighboring airline seats. Prices are just an information delivery system, the messenger that politicians keep wanting to shoot.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

If people don't like the price of Wendy's Baconator due to price hikes or dynamic pricing they could, IDK, eat at McDonalds. Government control of pricing never works

Or just tell people, including retarded US Senators, that Wendy's has raised the standard price but will sell at discounts during off hours.

Use facial recognition, so that notable politicians always have to pay $1000.

I was a child when Nixon imposed wage and price controls, and I remember the ferocious inflation and crap economy 1974-76 in the aftermath. Wage and price controls do not work, all it does is screw the middle and lower class both ways (wages, prices).

I pity the people of MA who elected the intellectual lightweight, Senator 'Pocahontas' Warren.

It's Fauxcahontas.

Fuckahontas?

Not even with*your* dick.

Not even with Sarc’s dick. Andhe’s the one member of the commentariat drunk enough to bang that hag.

His whiskey-dick would stop him.

The price controls on gasoline meant that oil companies lost money on every gallon of gasoline sold. To control the amount lost, they made less gasoline.

Remember the lines?

There was a genuine shortage of gasoline and other petroleum products; OPEC had considerably cut back the production of oil in many countries, and they picked a time when oil was already getting tight, so the non-OPEC nations could not expand production to compensate until they did a lot of drilling. The price of gas in my town, Traverse City, Michigan had risen from around 25 cents/gallon to around 35 cents, and oil companies already begun expanding exploration. In 1973 just before the oil crisis, my town, which had never had idea that petroleum was present at all, was suddenly full of Texans working on oil rigs. (What these wells eventually brought in was natural gas, not oil.)

But I don't think there ever were effective price controls. Government found a different way to screw up the supply of gasoline - allocating it to different areas as a percentage of the pre-oil-panic usage. I heard about the lines for gas elsewhere, but never experienced them myself. In my town, the main businesses were tourism and cherries. In a normal summer, the town population would triple as the hotels filled up with tourists, but with the high price and shortages of gasoline, tourism was dead. The new oil fields gave a few of the residents unusually well-paid jobs and brought in experienced workers from elsewhere, but not nearly enough to make up the difference. So we were allocated far more gasoline than even those with jobs could use - while according to the news, over in Detroit people could only buy gas every other day, and on that day they waited hours in line for 5 gallons. They certainly weren't going to get enough in their tank to drive 200 miles to us that way!

Price controls and their ilk are a politician's way of lying to you about what something is worth.

As are minimum wages. Ahh, but you got to that didn't you. Good Peter, your coworkers could learn a thing. But you should have really leaned into this point instead. I guess I'll do it instead.

In practice, minimum wage requirements drive up prices for consumers, and they can make it harder for the least skilled workers to find work by raising the price of low-skilled labor beyond what employers can afford to pay.

But more importantly, they distort the concept of value. As you put it, "what something is worth."

A Baconator is worth a certain value. As you put it, "How much should a Baconator cost? The answer is: It depends."

The same is true for a human being and their skillset. There are four basic determiners of human economic value, and it's measured in bargaining power:

High skill, High demand = High employee bargaining power.

Low skill, High demand = Employee favorable market based bargaining power.

High skill, Low demand = Employer favorable market based bargaining power.

Low skill, Low demand = High employer bargaining power.

I mean this is Economics - or should I say Capitalism - 101.

But we don't want to talk about that, do we. We, or those like Lizzy Warren, instead want to wander down the marxist road of "human dignity" and "living wages." As if people are owed, by right, more than they're worth. If only for sake of their continued existence (which only makes it all the more hilariously absurd).

It's that notion you should be trying to dispel here, Peter. Because the cost of a Baconator is directly proportional to the cost of the equipment and human resources needed to produce it, plus the profit to the producer who decides its worth his while to do so.

Take away the profit, increase the artificial overhead - you end up with an overpriced Baconator.

And then eventually no Baconator.

Minimum wage was created for the purpose of killing people. I'm not joking. It was created before any welfare or social safety nets existed, and it set the price floor for labor to what white union-workers were getting paid. This was a backlash against blacks who were migrating north for work and displacing whites by working for less money. Setting the price floor for labor above what employers were willing to pay meant that those blacks couldn't find work, and many of them starved to death. The hostility towards those blacks really wasn't that much different than the hostility towards illegals who work for less money. Can't set price floors for illegal labor, so the solution in their case is to round them and their families up at gunpoint and drop them off in some shithole where they have no economic opportunity. The motivation is basically the same.

The flaw in your equivocation is that blacks and whites in their own country can relocate with relatively same ease within the country for market based employment, putting them roughly equal competitively for the same market wage (all else made neutral).

That isn't so with illegals. Illegals allowed to compete in the local labor market doesn't translate to locals being able to compete in the illegal's home market.

Maybe removing minimum wage laws would diminish the need for illegals, but there's a big difference in the market value for an illegal shacking up with 15-20 other illegals in a rundown slum vs a local maintaining a modest or depressed American lifestyle. Bottom line is American living does have a minimum demand in cost that employers would like to avoid by giving the work to people willing to live in inhumane conditions.

At some point, employers need to be put to task for creating a system where THEY are exempt from market dynamics while the labor pool is not.

A generally good analysis, though you ignore the effect of oligopolies or oligopsonies on bargaining power.

Agreed and well stated. An interesting additional anaylsis would be how higher education controls the supply of some highly skilled labor (e.g. doctors, laywers etc).

Indeed, as well as how State licensing requirements control access to markets. The whole "gatekeeper effect," as it's called.

An example being how the taxi industry went bananas when ridesharing came on the scene, to try and preserve the fiat value of their "medallions."

So her next target is to eliminate the early bird senior discounts that keep Floridians alive?

The Amazon reviews for the "Pow Wow Chow" cookbook:

https://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/9996688445/reasonmagazinea-20/

"1.0 out of 5 stars Left me with a trail of tears.

I have thought about reviewing this book for a while, but I had misgivings. After realizing that my reservations made me more authentically Native American than it's author, I thought it best to write the review as a living record for my people."

American First Legal obtained photos of then-VP Joe Biden meeting with Hunter’s Chinese associates and Hunter meeting Chinese President Xi Jinping through litigation against the National Archives.

https://aflegal.org/america-first-legal-obtains-photos-of-joe-biden-meeting-with-hunter-bidens-chinese-business-associates-and-introducing-hunter-to-chinas-president-xi-jinping/

Biden has said over and over he never met or interacted with Hunter’s business associates.

The photos are from a trip then VP Biden took in 2013 to Asia and show him meeting with and taking pictures with Hunter’s business associates from BHR Partners, including Jonathan Li and Ming Xue.

In September 2023, subpoenaed documents showed that Hunter Biden used Joe Biden’s Delaware home address as the beneficiary address for payments from two Chinese nationals. One of those payments came from Jonathan Li.

Joe eventually wrote letters of recommendation for Li’s children to Brown University, Cornell University, and New York University.

In October 2019, The Wall Street Journal reported that BHR Partners counted Hunter as one of its nine directors since the company was formed.

Of course the National Archives only release the photos after the election and less than a month before Joe leaves office, which seems like more election interference to me.

It's (D)ifferent.

More like avoiding "interfering" with the election, i.e. making Joe and Democrats look (more) guilty.

If they do this, inevitably there will come a time when the price will change while I am ordering. If the menu board says $8.99 when I look at it, you can't digitally change that to $9.99 after I lower my eyes. Not unless there's some solid indication that the price changes at specific times of day. Otherwise you're in false advertising territory.

But here it's Wendy's which is masking and distorting prices. Prices don't do a good job of delivering information if they constantly change, especially in the context of fast food where you're buying one thing and you want it right now.

But, hey. Even if the price changes constantly, that doesn't provide *no* information. The information provided to me would be "you obviously don't want my business, and there's an Arby's right over there. And a McDonald's. And a Burger King. And a Culver's. And a Cousin's, a Subway, a Jimmy John's, a KFC, a Popeye's, a Taco Bell..."

" there's an Arby's right over there. And a McDonald's. And a Burger King. And a Culver's. And a Cousin's, a Subway, a Jimmy John's, a KFC, a Popeye's, a Taco Bell..."

Dig this: some people even prepare and eat food in special rooms called 'kitchens' in their own homes.

Not everyone is home all the time.

Not everyone has a home. But some of those who do actually prepare and eat food there, even if they are not at home all the time.

Yes, but not 100% of the time, and you still have to buy the food somewhere.

"But here it's Wendy's which is masking and distorting prices."

Other than your contrived corner case of Wendy's changing the price when you look away, (which no one except you has suggested) there is no indication that Wendy's is distorting anything.

There have been businesses running "digital menus" for decades now. Check the internet. And absolutely none of them has been accused of changing a price while you look away, though they will dynamically adjust price periodically. If this really was the "inevitable" outcome of digital menus, we'd have seen it already.

I've had Uber prices change before my eyes.

I'm not saying they'd purposely wait for me to look away. It's inevitable if they do pricing based on time of day. If they have different prices at 11:59 AM and 12:00 PM, someday I am going to walk in at 11:59, see the price, and have the clock tick (and thus the price change) before I order.

That's not inevitable with digital menus in general because you can change the price when no customers are present.

If they do this, inevitably there will come a time when the price will change while I am ordering. If the menu board says $8.99 when I look at it, you can't digitally change that to $9.99 after I lower my eyes.

Why the heck not? Heck, I've done this to people at garage sales and antique stores.

OK, Contract Law 101 - a contract isn't complete until the terms are offered, accepted, and consideration is made. If I've got a tchotchke that says $5, that's not a binding offer. That's an invitation to buy. The offer comes when the buyer expresses his willingness to buy at that price. (Literally every business in America that invites the purchase of a product at a price is one you can arguably haggle. Most people just don't bother in most markets though because, with set prices, a seller almost invariably isn't open to haggling. It often works at farmers markets, swap meets, both used/new car dealerships, and specialty stores though. And I've also done it with internet/cellular service providers, medical services, and artisans.)

Anyway, it's $5. At which point I could identify his eagerness for it, and say, "Actually, you seem to really want it so... $20." Or, "Well that guy wants it too, and he's willing to pay $10. Are you willing to offer me more than he is?" Both are legit.

And yes, it works the other way as well, where he could say, "I'll give you $3" and I, just wanting to be rid of it, take what's offered. Or, "I see you have 10 tchotchkes at $5 each. I don't want them all (might be lying), but I'll take the whole lot for $30 instead of 10x$5/ea.

I have personally experienced all of those situations. And others. The point is, acceptance doesn't occur until the terms are agreed to and the exchange is made.

So, you're in line for your Baconator, and Wendy's invites you to pay $9. You express a willingness to buy, but you look down for a sec and they suddenly increase it to $10. "Demand for [and therefore value of] Baconator's goes up a lot at this point," they might say. You're not obligated to pay $10 at that point. But you do have to re-evaluate (ie. make a value judgment) whether or not you still want that Baconator on the counteroffer price. By the nature of quick serve, the contract isn't complete until your money is handed over (at which point they're obligated to specific performance - ie. hand you your Baconator). It's not like they'd be able to hold up your sandwich in front of you and demand an extra dollar at that point. You've got the sales receipt as proof of your consideration - they have to give you the Baconator for the $9 you agreed upon when that was still the price.

So why does this bother you? What's the issue here? That you might have gotten something for a dollar less had you shown up five minutes earlier (or later)?

This is why it's foolish to hate prices

You were doing so well until this.

Hating prices is why McDonald's changed their business (even if temporary).

In fact, as information signalling goes, hatred of current prices (or the value they represent) is what drives people to pick x over y.

You would have been on firm ground by saying that hatred of prices shouldn't translate to control of them.

The Nixon Shock involved a lot more than wage and price controls including Tariffs!!!!!!!!!! But the most permanent damage was done when he defaulted on the US gold debt at Bretton Wood creating a world wide fiat currency system. What I could buy for a buck in 1971 now costs almost eight times as much. Wage and price controls can be cancelled and Tariffs can be renegotiated but we will never get our dollar back.

This^ Going to the fiat dollar also allowed the government to grow much larger.

The problem with the fiat currency is that it could, and did, get used to pay for significant deficit spending. Instead of Guns Or Butter, LBJ, instituting his Great Society, while waging the Vietnam War, ended up getting Gun’s AND Butter.

Inflation is always primarily a Monetary phenomenon - too much money chasing too few goods. Sen Fauxhauntis and her ilk try to address the symptoms of inflation, while, in her case, voting for more inflation in Congress by, in her case, spending $Trillions$ that we didn’t have, and funding it by, essentially, printing money, which, by necessity, increased the money supply, and, thus, causing inflation.

Let's be clear. Some people hate prices, but only in a vague begrudging way. But some people hate prices because they think that paying for what they want is "unfair", and that somebody (e.g. the government) owes them the lifestyle they want.

The former are a standard and necessary part of free markets, since we can keep prices in check through voluntary agreements on the value of exchange. The latter are leaches, and should be extinguished.

Interesting that Reason fully supports peak traffic tolls. I guess price controls are OK as long as government cuts out the middle man.

As I've said before, they hate cost increases. To an insane degree.

"How much should you pay? "

That's easy. The rule of thumb for restauranteurs is to charge 3 times the cost of the ingredients.

Restauranteurs don't say how much you should pay. You do.

"Restauranteurs don't say how much you should pay."

They do. Usually after the customer asks for the bill.

It's the restauranteur who decides how much to charge, and it's up to the customer to pay. As I mentioned, the traditional rule of thumb is 3 times the cost of ingredients. Customers can't reasonably expect to pay less than this, and needn't pay more.

BTW, that cartoon illustration should have Fauxchahontas in Indian princess garb, with war paint and a tomahawk.

"How much should a Wendy's Baconator cost? Elizabeth Warren thinks the government should help decide."

1. Senator Pocahontas knows as much about economics as her heroes Lenin, Stalin, Mao and Castro.

2. Demonstrating once again the profound ignorance of the ruling elitist class regarding rudimentary business practices.

3. I wonder how many of them ever worked in a fast-food restaurant, or for that matter, did any menial, hard, physical manual labor?

I heard of a case where a woman was briefly hospitalized after a minor traffic accident. Before treatment, a nurse came by the bed, held the patient's hand and offered a few words of re-assurance. The hospital billed the woman $US250 for the 'emotional comfort' the nurse provided.

But I thought insurance agents were the villains, not health care professionals and hospitals?

"We need to stand up to these would-be dictators and finally tell them 'NO!' - Who's with me?!" [sound of crickets]

"People hate prices. They hate rising prices. They hate persistently high prices. They hate complicated prices."

I disagree. People hate having to part with their hard-earned money for anything. If you want proof, take prices off menus and just give a bill at the end of a meal, and see how much people bitch then. They want prices, they just like their money and want to get things for as close to nothing as possible. That isn't irrational. It is common sense.

And political con-artists like Warren are there to lie to you every step of the way and insist that they can deliver you a free lunch.

Between this article and Sullum's "Inflation Breaks Peoples Brains" article, it is clear that Reason nurtures a superiority complex- holding our populace in contempt for irrational behavior. One of these days we might get an editor for this rag that understands the worst way to convince people to have free minds and support free markets is to call them irrational fools.

I've posted this before, but it's apropos of Warren's fascistic fantasies.

Economics of Fascism (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economics_of_fascism)

Mussolini's Fascist Italy

A number of mixed entities were formed, called instituti or enti nazionali, whose purpose it was to bring together representatives of the government and of the major businesses. These representatives discussed economic policy and manipulated prices and wages so as to satisfy both the wishes of the government and the wishes of business.

California:

AB 1228 – Fast Food Council

On September 28, 2023, Governor Newsom signed into law AB 1228, the Fast Food Restaurant Industry legislation that raises the hourly minimum wage rate for certain fast food workers to $20 effective April 1, 2024. In addition, the legislation establishes a Fast Food Council within DIR to establish an hourly minimum wage for fast food restaurant employees and develop standards, rules, and regulations for the fast food industry.

Don't forget, Mussolini and his buddies turned to fascism only after they failed at socialism. Not enough class anger (and difference) in Italy in the early 20th century.

Pierre Laval also started out as a socialist

Speaking of fast food, residents of Seattle are increasingly unlikely to tip.

https://townhall.com/tipsheet/saraharnold/2024/12/29/why-residents-in-seattle-refuse-to-tip-n2649720

According to a Daily Mail report, residents in the Democrat-run city feel it is unnecessary to tip service workers. The minimum wage will increase from $19.97 to $20.76 an hour on January 1, 2025. Seattle’s Minimum Wage Ordinance requires the wage rate to reflect the city's inflation rise.

One Reddit user said they are “done tipping 10-20 percent come January 1st,” while another person claimed that with the minimum wage hike, food industry workers have “finally reach[ed] a level playing field.”

“With Seattle’s new minimum wage going into effect really soon, most food industry workers are finally reaching a level playing field. As a result, I’ll no longer be tipping more than 5-10%. And I’m ONLY doing that if service is EXCEPTIONAL,” another person said.

“Any instance where I am ordering busing my own table, getting my own utensils, etc warrants $0. I also am not tipping at coffee shops anymore,” another user wrote.

Seattle’s minimum wage ordinance was designed to ensure a “living wage” for all workers, including service workers. However, the city’s push for higher minimum wages has had unintended consequences. Consumers are voicing frustration over "tipping fatigue," which is made worse by "tipflation," as suggested gratuities climb alongside wage increases.

"But here it's the government which is masking and distorting prices."

I say this because that's how the HOV lanes work. Surge pricing for government-owned (that is, taxpayer-funded) assets is just good sense, I'm told. And the price can change while you're looking at the sign trying to make your decision.

Ya know. Just like how 'armed-theft' criminals "thinks they should help decide."

Don't kid yourselves. Elizabeth Warren is praising armed-theft because 'armed' FORCE is all that 'government' is.

The left does this constantly. PRAISES 'armed-theft' acts like a criminal gang but likes to pretend its charity. "Here's my GUN now HAND over your goods/wallet. It's okay though; It's just ?charity?"

Dear Sen. Warren, you socialistic twit, the free market works because YOU aren't running it.

"It contains just shy of a thousand calories—about half the daily recommended intake for an average person, and more than twice the average caloric intake of the estimated 800 million people globally who are perpetually undernourished."

A quantitative observation worthy of Tuck Carlson or RFK Jr.

at 500 calories a day , people are starving, not malnourished, and few would survive long at 250.

Calories shouldn't be the bogeyman anyway.

Calories per dollar is a measure of effectiveness in spending your money on food, so you have more left over for other stuff.

It's why McDonald's used to be popular.

How much should a Wendy's Baconator cost? Elizabeth Warren thinks the government should help decide.

Ahhh, but of course, government already has "helped" decide the price of them, by imposing ever so many costs on us all, and devaluing our currency.

Idiot. The US dollar has been increasing in value against most other currencies.

...according to which lefty-lobbying group this time?

Is that why Gold is $2800 today and $1500 in 2020?

It has so much ?value? it'll only buy 1/2 the Gold it bought 4-years ago.

Other countries inflating their currency is not a reason we should inflate ours.

Ending rent regulations wouldn't reduce prices unless zoning regulations are sufficiently relaxed to increase the supply of housing. The New York City Council just enacted such a reform -- over the objections of every Republican member.

Can the Senate expel a member? Just asking, 'cause I've got a list and Warren is at the top of it.

And yet, she was just re-elected since her opponent wasn't conservative enough and not a Trump supporter. Congrats to my all-so-pure fellow Massachusetts friends, look who's back for another term.

The Constitution says "Each House shall be the Judge of the Elections, Returns and Qualifications of its own Members". This allows the House and Senate to investigate alleged election fraud and whether an elected candidate meets the age and citizenship requirements. It also allows each chamber to expel members for corruption and other misbehavior in office (I think a 2/3 vote is required by House and Senate rules).

But the Supreme Court ruled in Powell v. McCormack that if the voters return them to office in another election, the chamber cannot refuse to seat them because of the previous charges. (Probably they could be admitted, then expelled again, but the House could not muster the 2/3 vote to expel Powell a second time.) So for Elizabeth Warren:

1. If the Senate rules are anything like the House rules, you'll never get a 2/3 vote for expulsion.

2. If you did, she'd be back as soon as Massachusetts could hold a special election to fill the vacant seat.

But should be government price the Baconator cheap, to help hungry poor people, or price it high, to discourage consumption of unhealthy food, since "we" all bear the public health costs?

Thomas Sowell said it best: "The first lesson of economics is scarcity. There is never enough of anything to satisfy all those who want it. The first lesson of politics is to disregard the first lesson of economics."